Do Androids Dream of Electric Pigs ?

Basic information

Project Title

Full project title

Category

Project Description

Les androïdes rêvent-ils de cochons électriques ? [Do androids dream of electric pigs ?] is an exhibition presented by Marie-Haude Caraës at the Saint-Étienne International Design Biennial in 2013. The intention of this exhibition, conceived by the Cité du design's research department, was to give an account of designers' work on the theme of animality : a tactile approach to portraying the sensory experience of the designer, a zone where the tides of humanity and animality converge.

Project Region

EU Programme or fund

Description of the project

Summary

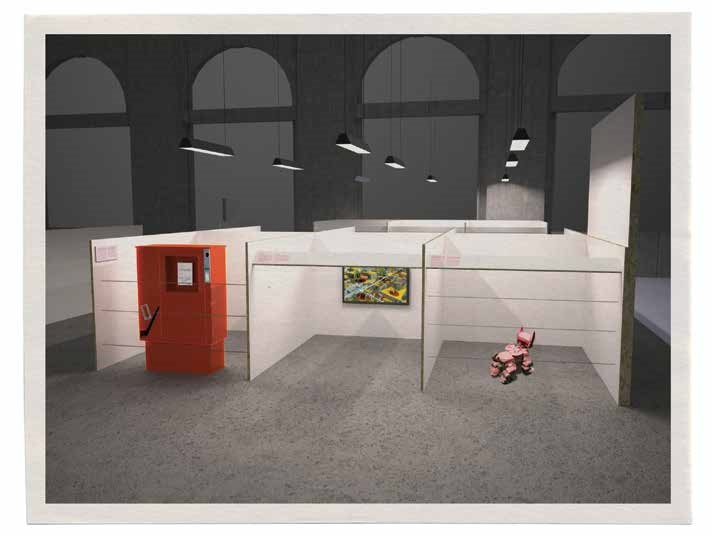

Les androïdes rêvent-ils de cochons électriques ? [Do Androids Dream of Electric Pigs ?] is an exhibition presented by Marie-Haude Caraës at the Saint-Étienne International Design Biennial in 2013. The intention of this exhibition, conceived by the Cité du design's research department, was to give an account of designers' work on the theme of animality : a tactile approach to portraying the sensory experience of the designer, a zone where the tides of humanity and animality converge. The exhibition was created with Claire Lemarchand (assistant) and Adrien Rovero (scenographer).

This exhibition refers to Philip K. Dick's science fiction novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? in which the nuclear disaster took place.

Friends of W. C. Fields have said of this famous actor of the silent era: “Someone who has contempt for dogs and children cannot be completely bad”. Reversing, in a few words, all that humanity holds dear is always an admirable feat. How then can we avoid slipping into such mawkish or affected attitudes, when exploring the role and status of animals in our society, within the context of the Biennale? It’s not even by seeking to define the significance of the animal kingdom — a challenge in itself — that we are led into a deep ontological questioning of the substance and form of contemporary reality. This Copernican revolution of thought and awareness makes us simultaneously look back over our shoulder as we launch ourselves, anxiously towards the emerging world.

Four pieces of work — “Pigs in the park”; “The animal, from the inside”; “Survival of the fittest”; “The new wildlife” — explore the theme of mankind’s exile — “the great divide”, in the words of the philosopher. The art historian Siegfried Giedion notes with sadness that industrial mechanisation has its basis and foundation in the Chicago slaughterhouse — whose process was the inspiration for Henry Ford’s factories.

Key objectives for sustainability

This exhibition promotes sustainability through the proposed reflection on the relationship between humans and animals.

Through centuries of coexistence, animals have served a wide range of purposes for the benefit of mankind: from being exploited for their resources to being domesticated by the adaptation of their animal instincts to meet our human needs: hunting, farming, transport, communication, etc. Most of the practical ways in which animals were used have gradually disappeared and have been replaced by technology: this progressive eradication of animals will become the contemporary equivalent of banishment to the ends of the world, even if animals continue to be exploited for their meat, skin, organs, and even their affections. Herein lies mankind’s schizophrenia: on the one hand, the farmer exploits calves, cows, pigs and hens in order to assure his comfort and survival, whereas on the other hand — stricken with guilt — he seeks to put a stop to the subordination to which he has consigned animals. The multiplicity of animal artefacts (furniture designed for pets, toys designed to distract industrially farmed piglets, etc.) may point to mankind’s ambivalence towards this lesser being. As, no doubt, does the emergence of the concept of “animal welfare” in the slaughterhouses, in the laboratories of experimental science, in industrial farming. There are also initiatives lobbying for the reintroduction of animal traction in the fields and even in the towns; farmers fight to preserve breeds of cattle that have almost disappeared under the yoke of industrial rationalisation; animality is becoming a subject of the philosophical and anthropological avant-garde. In the wake of the criticism of mass industrialisation, there has been a focus on the relationship between mankind and machines. But what about animals? What role and status do they have in our hi-tech world? How do designers perceive animality?

Key objectives for aesthetics and quality

The exhibition gives an account of this particular and renewed aesthetic of animality.

How do designers perceive animality?Are there any works that provide answers to these questions? And which system would be most suited to presenting these works? How can we avoid creating the effect of a complete denunciation? How can we prevent creating generalisations? How can we reflect that our knowledge of the animal kingdom is incomplete and fragmented? Are all issues that have been raised in the conception of this exhibition.

The idea of exile haunts designers who refuse to accept the disintegration of living beings, the dismantling of the world, the emaciated life. In the light of its aesthetics, design enables humanity to experience the metaphysics of life in all its forms.

Key objectives for inclusion

Inclusion is one of the fundamental issues, through the reflection of the relationship between humans and animals.

About this subject, Gilles Deleuze writes “It’s not a case of man or beast, or any physical resemblances, it’s about a fundamental identity of substance, a zone of indiscernibility that goes deeper than any sentimental identification: human suffering is a beast, the beast is a man who suffers. This is the future reality. What man […] has never felt a moment of sheer bestiality, and has therefore become responsible, not for the calves dying now but for the calves that will die in the future?”

Results in relation to category

The exhibition consists of four pieces of work — “Pigs in the park”; “The animal, from the inside”; “Survival of the fittest”; “The new wildlife” — explore the theme of mankind’s exile — “the great divide”, in the words of the philosopher. The art historian Siegfried Giedion notes with sadness that industrial mechanisation has its basis and foundation in the Chicago slaughterhouse — whose process was the inspiration for Henry Ford’s factories. Designers constantly challenge the way in which the world is organised. In post mortem the Dutch designer Christien Meindertsma has documented all the products made from a single pig numbered 05049 in the industrial chain. After its death, pig number 05049 was dissected and all its vital organs were removed and used in the production of industrial objects. In a similarly critical vein but using different techniques, Matthew Herbert, the English musician and producer of electronic music, creates a sound biography of the life of a single creature — One Pig — from birth to plate. In Safety Gear for Small Animals, Canadian artist Bill Burns continues this theme with a collection of twenty-three items of security equipment for small animals, such as otters and beavers, that inhabit the Canadian forests. Is this going too far? Bill Burns quips, imagine the absurdity of a raccoon wearing a reflective vest or an otter wearing a gas mask. Some designers have already decided to portray this irreversible global trend: the Mexican artist Gilberto Esparza used electronic spare parts to create living organisms that feed on urban energy infrastructures such as power lines. Other designers try to reconnect with mythology to salvage what can still be used: the French designer Benoît Bonnemaison-Fitte draws giant charcoal yetis that transcend the limits of mechanical reason and move towards a futuristic animal.

How Citizens benefit

The exhibition was open to the public from 13 to 31 March 2013. Taking place within the framework of the Saint-Etienne Biennial, which has a very large audience, it allowed everyone to have access to these reflections.

Innovative character

The innovation of this exhibition lies in the fact that it presented design projects that were themselves innovative in their focus on animality and human-animal relations.