Co-created neighborhood libraries

Basic information

Project Title

Full project title

Category

Project Description

What would a library look and feel like if it was created together with your neighbors? The library could be a place where you engage in meaningful activities with your community. Through the process of creating the library, you can participate in the circular economy, heal the surrounding natural environment and learn sustainability in practice. Everyone is encouraged to join the library, which is constantly evolving and coordinated by your neighbors. Expert guidance and funding are provided.

Project Region

EU Programme or fund

Description of the project

Summary

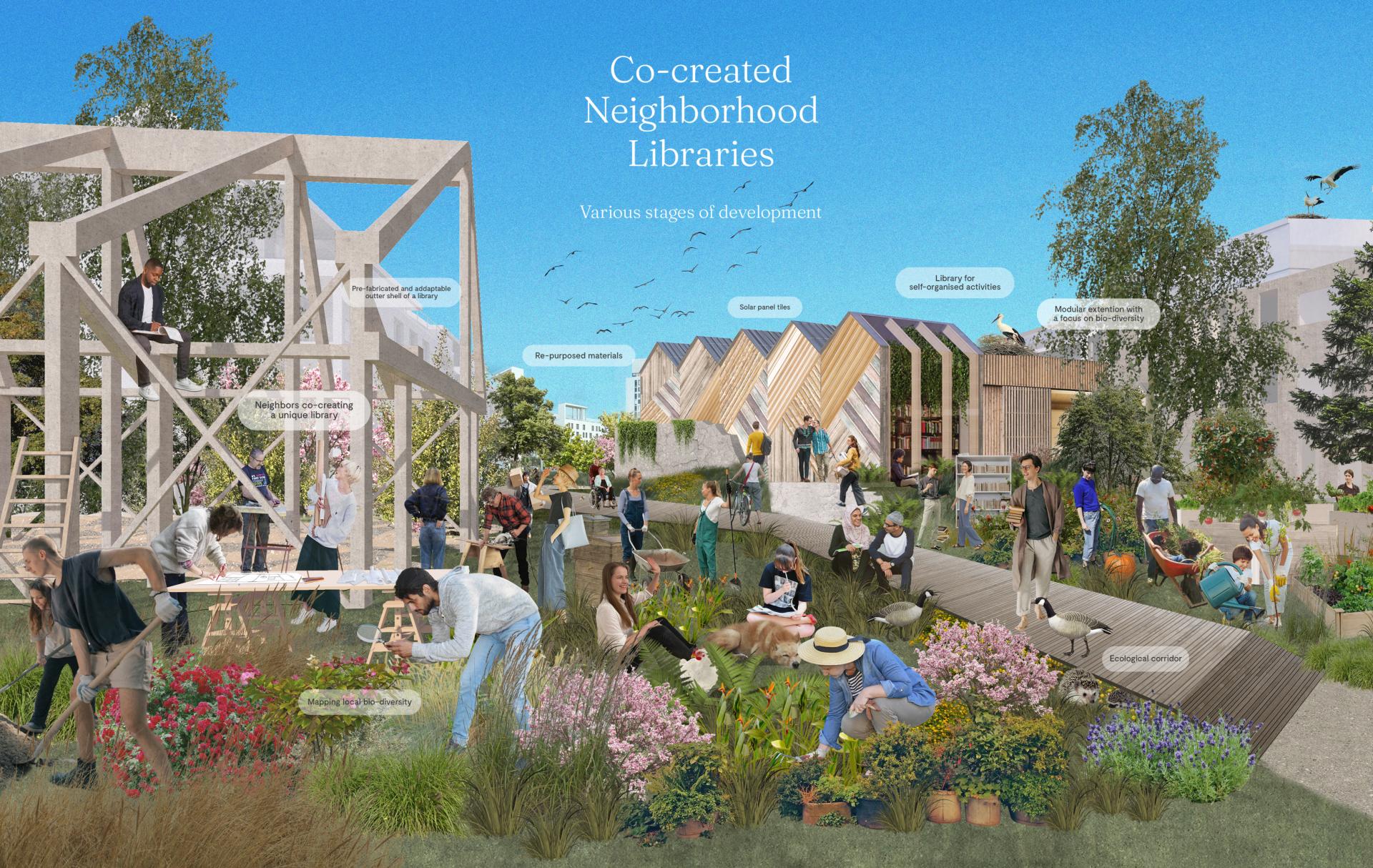

Co-created Neighborhood Libraries (CNL) is a model for infrastructuring participatory design grounded in the regenerative circular economy. We propose a model for how sustainability transitions could be realized at a local level while promoting social resilience. Democratic participation in sustainability transitions is crucial for just transformations. Neighbors are enabled by trained co-designers or local facilitators to define, design, build, maintain and adapt neighborhood libraries in an ongoing process according to evolving needs. Following, aesthetic qualities are co-created and defined by the diverse inputs from residents through circular principles and ecoregional renewable resources. Co-created libraries provide space and conditions to share knowledge and facilitate meaningful neighborhood encounters. Our model contributes to community well-being by addressing basic human needs like belonging, creating and learning.

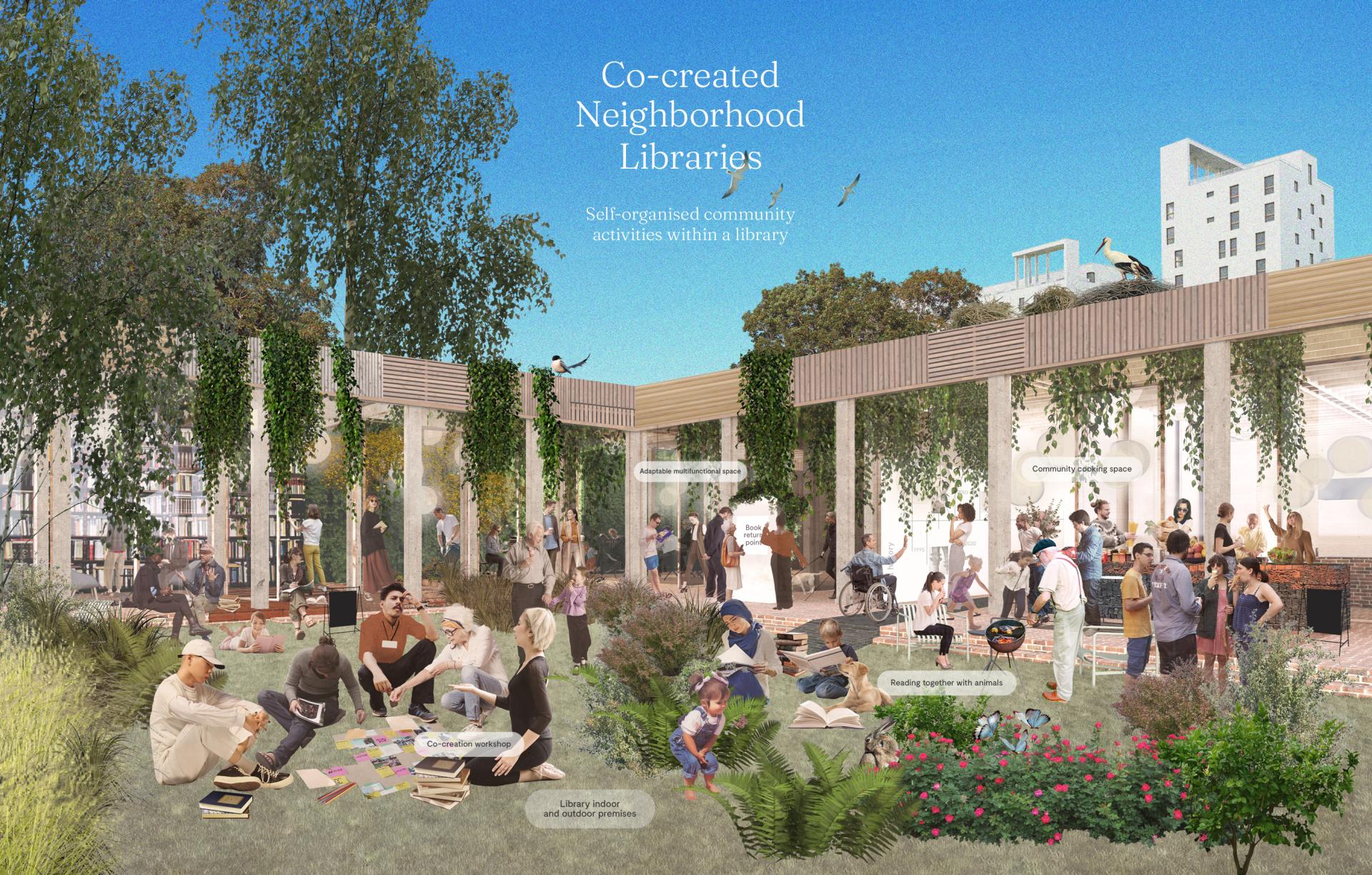

Our model broadens the scope of libraries, from perceived book-lending facilities to include neighborhood knowledge hubs for local regeneration. The function of libraries expands from more general knowledge providers to distributed and open-ended knowledge mediators unique to the creativity of neighborhood residents. The insights and empowerment from participatory design processes could gradually evolve to regenerate the library surroundings and native biodiversity. In our visualizations, surrounding areas are developed to promote universal access and space for other species as well.

Our model for infrastructuring neighborhood libraries can be applied and adapted to various local contexts.

The proposal was initially part of a school project at Aalto University in collaboration with Espoo City Library; we have since evolved the model further.

Key objectives for sustainability

Sustainability and community resilience are the foundation of our proposal, and thus the model of CNL integrates sustainability in every stage of the process. In terms of the building materials used, circular approaches such as reusing existing materials and repurposing demolished parts of existing buildings are central (SDG 12, Responsible consumption and production). We recognize that the building and energy sector requires rapid transformation; therefore funding for solar panel tiles to choose from can also introduce residents to energy transitions while powering the libraries. Through introducing sustainable technologies and methods at the local level, sustainability becomes an integrated part of everyday life. To counteract the biodiversity crisis, sustainability is not sufficient, and thus regenerative work must also be prioritized.

Native biodiversity and rewilding practices are not something that happens somewhere far away but are connected to the everyday activities surrounding the libraries (SDG 15, Life on land). Local knowledge creation grows in parallel -and contributes to ecosystem resilience and climate adaptation (SDG 13, Climate action). For example, ecologists could help and train library workers and neighbors to maintain or expand the local biodiversity of species to create unique features for the libraries outside as well.

Public participation is essential to reinforce sustainability transitions; therefore, the CNL model channels opportunities for broader involvement. Instead of learning about concepts like the circular economy in a talk at the library, people would experientially participate in circular practices while creating and reconfiguring the library at multiple stages. To facilitate the participation of new community members, the library is open to configuration. Instead, it is a "work in progress" that uses the concept of adaptive governance to answer emerging needs from evolving demographics.

Key objectives for aesthetics and quality

The neighborhood libraries are manifestations of local community identity, which defines the aesthetics of the buildings and the surrounding environment. Instead of imposing expert visions alone, community-built libraries generate unique aesthetics that reflect the mosaic of people involved and strengthen local cultural identity. Aesthetics are defined in co-creation workshops by and for citizens, and if needed, facilitated by co-design professionals. As a result, community co-created aesthetics reflect the participants' input and circular material sourcing.

The first community-built libraries are intended within the bioregional context of Espoo, a part of the Baltic Ecoregion. Therefore, local natural resources influence the building's aesthetics. By using a small share of virgin renewable materials sourced from this bioregion, we create a model for unique spaces situated in the local context. For example, in Espoo, wetlands with reeds are common and are thus used as decorative elements that accommodate native bird species. Designing with other species in mind can mitigate the biodiversity crisis, resulting in aesthetics of connectivity. In our example, ecological corridors are prioritized through universally accessible wood paths rather than asphalt or rocky roads.

Since the future is circular, buildings from the New European Bauhaus should promote circular aesthetics. Therefore we reference Muuratsalo Experimental House by Alvar Aalto with the patchwork of bricks, showing how the reuse of bricks can make the circular economy look appealing and desirable. Simultaneously, we want to move away from the excessive cleanliness and simplicity of the modernist era, which also supports the ideas of shiny and new materials. It is an aesthetic shift towards ecoregional, reused, and continuously maintained buildings that can also promote the feeling of home and connection to the natural environment.

Key objectives for inclusion

Co-creative practices in CNL are used for direct participation and involvement to create the neighborhood library, transform participatory approaches from a mandatory minimum, and become a fundamental driver of the model. CNL seeks to address the diverse needs of residents in Espoo; over a fifth of residents have another native language to Finnish. Community participation can be encouraged by hiring local people from otherwise underrepresented groups (SDG 10, Reduced inequalities). Providing space for regenerative activities to engage with neighboring communities is especially crucial to those excluded or retired from market labor today; typically refugees, youth, seniors, and otherwise disabled people. Libraries are free for everyone, and in CNL, access is further promoted through proximity and trained facilitators, both from within the community and various experts during the initial stages. Neighborhood libraries should have space for diverse contributions agreed upon together, with a low threshold for suggestions.

Following the logic of regenerative development, the sense of ownership and belonging to your surroundings will strengthen by providing space and unfolding your neighborhood's creativity to take action on shared visions (SDG 11, Sustainable cities and communities). The use and design phase of the library is inseparable, as neighbors will configure the interiors while changing, repairing, and maintaining the exteriors. Providing life-long learning is another aspect of libraries. In community-built libraries, learning adapts to local conditions, and practical know-how becomes accessible for everyone (SDG 4, Quality education). By learning through doing with experts, practical aspects and implications of sustainable material use and consumption become evident through including the ecoregional impacts. Finally, the inclusivity of CNL seeks to establish a democratic base for just sustainability transitions.

Innovative character

The innovative character of our CNL model is mainly the systemic and transdisciplinary open-ended development process. Key aspects of the model are: the localised approach with continuous involvement; ensuring democratic participation in sustainability transitions; and expanding the purpose and function of libraries.

The transdisciplinary development process through actively seeking non-expert knowledge ensures that the needs of local communities are defined and met accurately. Adaptive governance and public facilitation for bottom-up approaches should be prioritized to implement the process. Library workers and other experts' facilitation of co-creative processes applies to many levels:

- mapping community needs for library staff and facilitators

- creation and sharing of practical knowledge, based on neighborhood capabilities

- training community skillsets for contribution in a co-creation process

- co-definition of the functionality of the indoor and outdoor spaces of a library

- co-creation of design and architecture of the library

- building the library and improvement of the surrounding outdoor spaces

By piloting the co-creation model of the libraries in neighborhoods, the commonly shared meaning of the library broadens. The library becomes a neighborhood knowledge center and hub for local regeneration. The functionality of indoor and outdoor spaces and resources the library provides expands to address local neighborhood needs on their own terms. For example, in the Espoo City Library case, the outdoor spaces could be dedicated for social interaction, knowledge sharing, learning, community work, and leisure.

Our innovation answers to the diverse objectives of the Finnish Library Act of 2016, like "availability and use of information"; "opportunities for lifelong learning and competence development"; and "active citizenship, democracy and freedom of expression"; "implemented with a sense of community, pluralism and cultural diversity".

&