INHABITING AN ENCLOSED LANDSCAPE

Basic information

Project Title

Full project title

Category

Project Description

The material isolation of the Balearic Islands made its inhabitants develop their own material culture out of the island’s limited resources. This enclosed landscape gave shape to sustainable techniques that deeply align with our current search for circularity and can thus be brought into the future. Together with the Balearic Institute of Housing, we are developing a 10 social housing units scheme that updates sandstone and timber construction while taking advantage of its sustainable nature.

Project Region

EU Programme or fund

Description of the project

Summary

The historical inhabitants of the Balearic Archipielago knew, unlike the moderns, that landscape has no rear as they were forced to live on an enclosed habitat facing the results of their actions. While culturally connected through the Mediterranean, this material isolation made them develop their own material culture out of the island’s limited resources. The enclosed landscape gave shape to sustainable techniques that deeply align with our current search for circularity and can therefore be brought into the future.

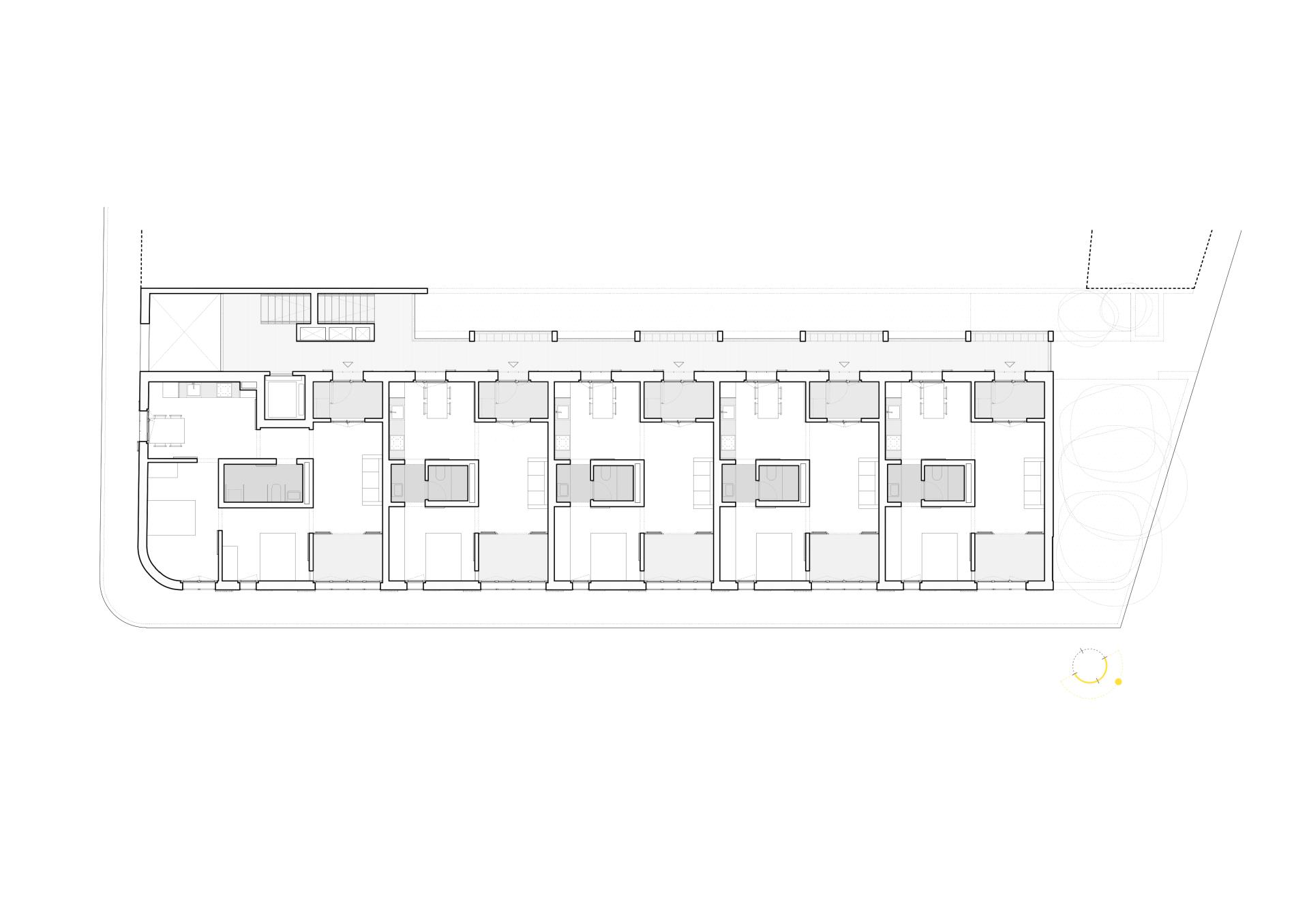

Together with the Balearic Institute of Housing (IBAVI), we are developing a social housing scheme that updates sandstone and timber construction while taking advantage of its sustainable nature. The scheme is located on the outskirts of Santa Margalida, a small town on inland Mallorca, and comprises 10 dwellings and as many workshops on ground floor. The strategies behind this design tackle the two major emergencies faced by the region: climate emergency and housing emergency.

Concerning the climate emergency, strategies for the reduction and creation of energy will be implemented during construction and use of the building as explained later. To be able to achieve the high sustainability standards we are working at the junction of vernacular local knowledge and the contemporary building industry.

As an immediate result, the building will provide shelter for 10 local families to address the housing crisis in the islands. Nevertheless, the ultimate aim of this public prototype is to reactivate the local building industry, so these traditional methods are updated and standardized for broader use across the region. Therefore, the scheme affects different aspects of social sustainability: access to the housing market, update and conservation of local traditional industry and creation of economic opportunities in rural areas.

Key objectives for sustainability

The project is conceived as a prototype on a series of buildings developed by the BIH. The solutions studied will therefore have a bigger impact than the building itself: they will be lab tested and published so they can be used elsewhere with the titanic but hopeful objective of changing the local building industry.

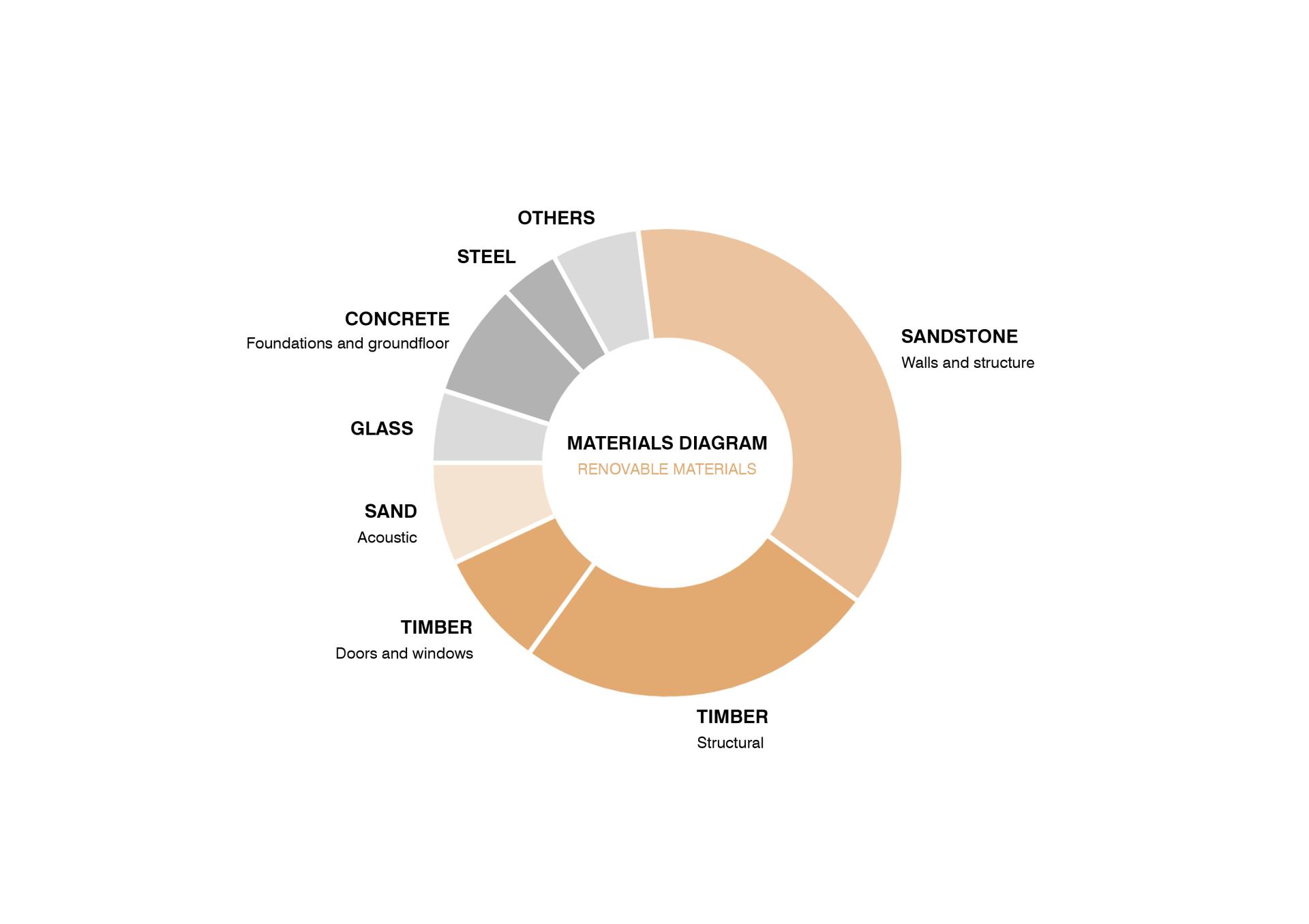

Quantifiable objectives include the lowering of energetic consumption to <17,20 kW/m2 per year, 100l water per inhabitant a day, and reduction of 25% of CO2 emissions during construction in comparison to standard buildings. To meet these standards, we need to tackle two main phases: the material resources used for construction and the energy management during its expected lifespan.

In the first phase, materials that required fossil fuels for production, such as steel or concrete, have been kept to a minimum. To achieve this we have looked back to traditional timber and sandstone techniques and, together with local stonemasons, we are critically adapting and updating them to currents standards.

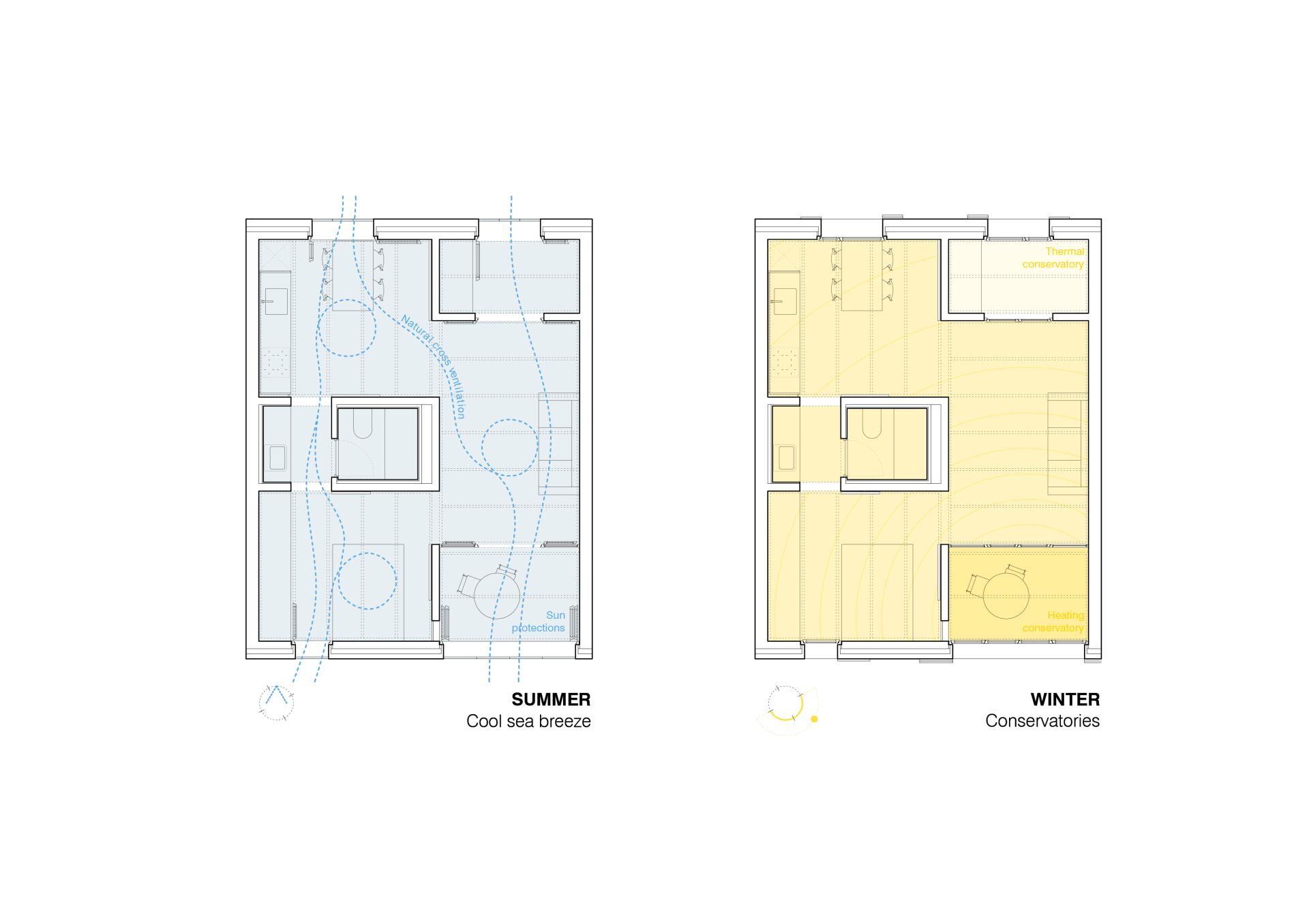

Many strategies will also be implemented to reduce the energy consumption once it is inhabited without affecting interior comfort. Significatively, these as well will be a mix of vernacular knowledge and state-of-the-art technology. The very shape of the building promotes different strategies: it becomes a screen oriented to the cool sea breeze during summer months and sunlight on the coldest months, its shallowness increases interior draughts and helps dissipate embedded heat, the thermal mass of the stone will keep the interior temperature stable throughout the year. Sun energy will be used on two different systems. Solar panels on the roof will produce HSW. Every living room façade has been made into a conservatory that will radiate heat to the interior during cool months but could be open and shaded the rest of the year, becoming an outdoor terrace. Once these strategies are effective, the building will become a thermal low-tech device.

Key objectives for aesthetics and quality

Aesthetics is both consequence and expression of our society’s management of resources: the tangible manifestation of a way of living. Therefore, new aesthetic categories can only be created by changing the core principles of our design practice.

Consequently, the aesthetical value of the project will be rooted in an ethical first principle: to accept and embrace the specific conditions of the place and its transience. The scheme will work with reality accepting patina, decay, weather variations, and irregularity as valuable assets. This acceptance, present on other aesthetical traditions like Wabi-Sabi, will give our design dynamism, as it will be able to grow, change and adapt during its lifetime. The limited palette of natural materials will be aligned with this vision and will help the building improve over time.

The building will magnify the experience of the site and place: it is a device that increases awareness about natural phenomena and helps dwellers interpret its surroundings. While this role was widespread in past architecture, some of the first buildings we know being sacred settlements used as calendars, it’s not so common today. Current interiors tend, on the contrary, to be isolated from their habitat in pursuit of sustainability. On our project, the layout of the dwelling will follow the sun path during the day like a solar clock that will help understand nature cycles through the careful positioning of windows. Exposed sandstone and timber will increase the awareness of the origin of building materials and surrounding landscape.

Precisely, this physical experience will have comfort at its core, as something that needs to felt rather than thought. The materials will give the interior a certain warmth and thermal inertia that, together with Mallorca’s gentle climate, will allow for a hedonistic enjoyment of the weather. In a time of growing online interactions, this subversive approach vindicates the value of our physical presence and body.

Key objectives for inclusion

Inclusivity is rooted in the project nature by its social origin. The uncontrolled tourism in the Balearic Islands has raised the housing price at the highest rate in the country, particularly affecting the most vulnerable sector of society. While this building can only have a limited effect on it, together with a larger stock of public housing it can affect the housing price so spaces are affordable for the locals.

The evolution of the nuclear family into diverse structures and the absolute need for gender equality have had a great impact on housing layouts. Each unit is conceived as a continuous space around a central piece creating a circular path that crosses every room. This way, every space and action are of the same importance: house chores and appliances are no longer hidden but integrated into a new domesticity. The flat layout is also adapted to an upcoming society. Every bedroom being the same size allows for atypical families to inhabit these apartments that can be equally shared by people with different relationships: parenthood, friendship, romance, or mere home-sharing.

In terms of use, the legal requirement of a parking spot for each housing unit has been addressed with a subversive approach that eventually enriches the project. Instead of creating a unified underground parking floor, car spaces have been located at street level and are designed in a way that can be used as workshops, offices, or shops in direct relation to the street. We want this building to work for a more inclusive city that rejects the hegemony of private cars and moves towards an alternative transport system based on public strategies. Furthermore, these spaces have been fitted on the same load-bearing wall structure that shapes the dwellings, so every two locals can be made into one flat once regulations are free from the tyranny of fossil fuels. This creates an immediate alternative of use and a future-proof solution that will allow us to provide more housing units.

Innovative character

The original Bauhaus set the basis for Europe’s design culture in the intersection of technical rationality, radical pragmatism, and unprejudiced exploration. However, today’s context requires updated criteria that are embedded on our design:

- From standard to specific: While knowledge needs to be global, application must become specific, an answer to local conditions. Working like this, shared ideas across the continent would however result in diverse spatial experiences and aesthetics that are deeply rooted in its local context.

- Resilience: Instead of opposing, we are working our way around the different inputs that shape the building, including those that radically opposed the nature of the project like the need for parking spots turning them into opportunities.

- Counterparts as resource: in the search for a closed cycle this project looks into vernacular long-term strategies that accept and incorporate surplus and counterparts into their constructions.

Off-centered: An increased awareness of natural phenomena sets us back from the centre into post-humanism, a humbler position that takes all our environment into account.