Drawing as a common language.

Basic information

Project Title

Full project title

Category

Project Description

Handmade drawings are extremely efficient for making scientific culture more accessible.

From children to scientists, and from the development of animation techniques to their application at large scale in scientific museums, this long-term project extended drawing with new possibilities of transformations.

It was finalized with a PhD documenting the perspectives and the sustainability of those productions.

Project Region

EU Programme or fund

Description of the project

Summary

nThis project explored the fundamental role of drawing in the cohesion of our society through a focus on the accessibility of sciences. In the 1990s, the rise of digital images posed a serious challenge to handmade drawing, while today this practice appears more and more relevant to both green and digital transformations. The main achievement of this long-term project was to show that drawing is so fundamental in our culture because it builds a common space of representation.

The first step, in the early 2000s, was to extend the capacities of drawing in terms of movement and transformations: how could we make handmade drawings move with the same fluidity as 3D images? This raised aesthetic challenges involving movement analysis and dance as well as computer graphics. The answer came through the development of morphing-based animation (fig. 1)

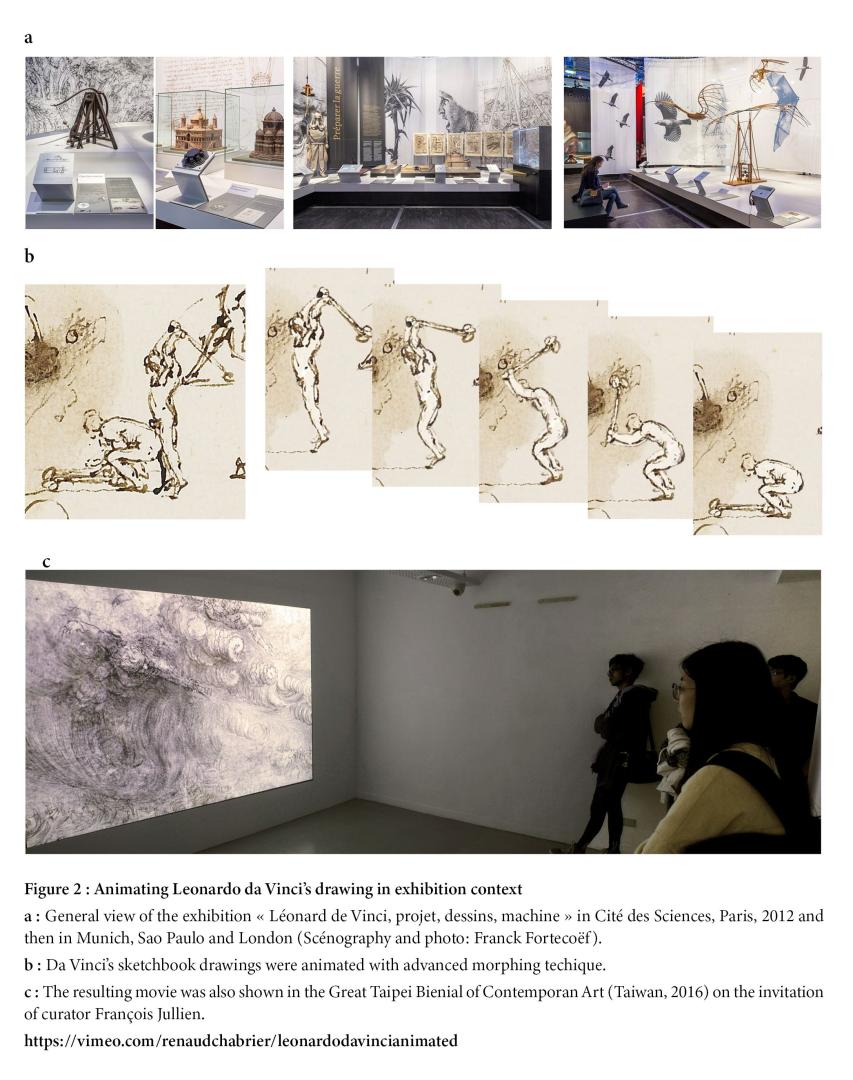

The second step was to use those capacities in real productions. Books, movies and museographic installations were produced, principally in the Cité des Sciences et de l’Industrie in Paris (fig. 2). Children contributed to experimental workshops at the beginning, in the next stage participation by the general public was key, and researchers involved themselves for the final development of the project. The resulting productions proved their sustainability many years afterwards.

The last step was to convert those experiences into transmissible scientific knowledge. In order to further explore the relationship between drawing and life sciences, I prepared an interdisciplinary PhD in Art and Design involving a large scientific community. The thesis I defended through video conference in November 2020 showed how the common space of representation created through drawing can be explained in terms of movement and transformations.

On the basis of this project, drawing appears to be one of our most important ways to access, respect and share the geometry of life. This makes it key to the success of the New Bauhaus.

Key objectives for sustainability

The sustainability of many drawings from the Renaissance or from the 19th century is obvious: 120 years later, the drawings of Ernst Haeckel (who invented the concept of “ecology”) are still one of the most valued representations of biodiversity. How can we try to achieve this level of sustainability with the representations of life we produce today?

The solution could not come from digital 2D techniques (improperly called “vector graphics”). Since they are fundamentally “flat”, they are not suited to the representation of life in real space, and they are clearly dedicated to superficial short-term communication. The solution could not simply come from digital 3D techniques either, because virtual cameras are bounded to a “point of view”: like photography, such images are very tied to one particular place and moment. Since conventional 3D does not create a common space for representations, it cannot promote the long-term circulation of ideas.

Fortunately, Renaissance and Modern art provide solutions for creating spatial representation “without a point a view”. This is essential in da Vinci’s way of sketching, but also in modern dance where choreographies were no longer supposed to be viewed from one specific place. Consequently, I invested a lot of time in learning hand and body techniques, and then I applied the same composition logic to scientific transmission.

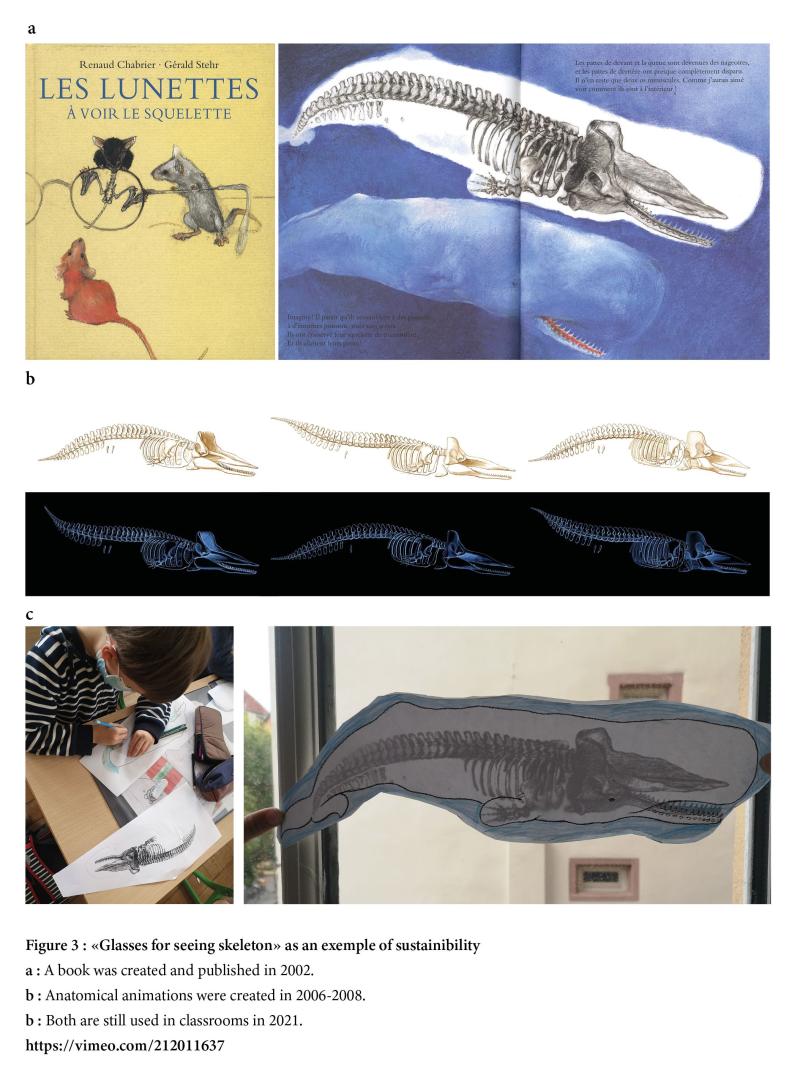

The results are clear: 20 years after it was made, my first book for children “glasses for seeing skeletons” (“Les lunettes à voir le squelette”, fig. 3) is still in demand and used in France for the introduction to anatomy in schools, without any marketing support. Similarly, the short movie “Birth of a brain” (”Naissance d’un cerveau”, fig. 4) made in 2014 for the Cité des Sciences et de l’Industrie in Paris, has become the preferred accessible presentation of neurodevelopment.

Key objectives for aesthetics and quality

Beyond functional challenges like giving correct ideas about proportions, the quality and aesthetic in scientific representations strongly depend on our ability to handle textures. These material dimensions of representations imply traditional skills concerning tools and paper. It also means that digital animation choices must be coherent with this aesthetic.

In 2000, morphing appeared to be the solution to that question. Through precisely controlled deformations of a texture, it allows us to make drawing move in a very fluid and subtle manner. I mastered this technique through 10 years of developments, experiments and projects, from the animation of portraits to anatomy in movement for natural history museums. In 2012, I was able to produce my “masterpiece” by animating a complete set of Leonardo da Vinci drawings in the context of a large exhibition at Cité des Sciences (fig. 2). This work shows how science and aesthetics can connect through the combination of drawing, movement and music.

The rise of video mapping at the end of the 2000s provided a fantastic opportunity to explore further. In several scientific exhibitions, I was able to pioneer the combination of model scales, animation and projections. With my production team, we evoked a Gaulish Ceremony in a sanctuary, or the transformations of a medieval village over four centuries. In such cases, the aesthetic of drawings was fundamental for functionality: it allowed hundreds of thousands of visitors to share the experience and build common representations of the past.

Finally, with researchers like Matthieu Piel, Ana-Maria Lennon-Dumenil and Carsten Janke, we promoted the uses of drawing for more aesthetic representations of modern life sciences. With Institut Curie and partners such as the European Molecular Biology Organization, we realized this project in multiple ways, from designing scientific figures and concepts for publication, to telling the story of immune cells to teenagers (fig. 5 and 6)

Key objectives for inclusion

Accessibility of science is one of the most challenging issues for democracy today. Important decisions must be made based on scientific knowledge, yet many scientific fields have become less accessible during recent decades because of specialization.

Thanks to my scientific background, I had the opportunity to design visuals and stories for several communities, which differed greatly in terms of expertise: researchers were mainly focused on “hot topics”, the general public needed a lot of context and background information, and children were discovering almost everything for the first time.

However, I was surprised how the same drawing could be used with the three kinds of communities, if and only if it included enough contextual information. Typically, instead of showing an isolated schematic cell, it is possible to show the tissues and organs it belongs to. On this basis, text and explanations can be adapted to fit the expertise of the audience in question. Most of the time, specialists are glad to benefit from this work too, because context always opens up questions outside of their usual field.

I often insisted on raising the level of scientific information in science exhibitions, since I was confident that anyone could engage with proper drawing, animation, and storytelling work. Investing time and money in documentation and representation work proved extremely rewarding afterwards, since it allowed presenting and debating between different people at different ages.

During recent years, the project was focused on a recurrent problem: understanding the scale of cells, viruses and molecules is exceedingly difficult for most people. For the new QLife Institute in Paris, I created an animation which zooms in and out from the entire body down to the scale of DNA (fig. 6). Pastels were used for drawing the different steps, inspired by Pasteur’s drawings. This work demonstrates that a clear feeling of the multi-scale aspect of life can be made accessible.

Results in relation to category

This project has been involved in many important exhibitions in humanities and sciences (In Cité des Sciences: “Gaulish”, “Middle Ages”, “Brain”, “Vinci”, “Pasteur”…) each attracting more than 200,000 visitors in Paris alone. Thus it significantly contributed to the building of common scientific culture in France and other countries.

The morphing-based animation of drawing demonstrates how techniques, arts and culture can be mobilized for that purpose. In the 2000s, this technique allowed the achievement of a long-held dream: to make ancient drawings and paintings move. But how they should move was not specified by the digital tooI: expertise in traditional animation and dance was required to determine that. Furthermore, since the transformation of an image affects its texture as well as its meaning, a knowledge of history is needed to do it well.

This approach allowed me to animate European art from throughout history: cave paintings from the Grotte Chauvet and Lascaux, the Gundestrup Cauldron from Denmark, paintings from Pompeii, Lorenzetti’s “Effects of Good Government” fresco, da Vinci’s drawings… Arte, CNRS Image and several museums in France provided significant dissemination of these animations.

This work was influential in popularizing the use of animation in TV documentaries. One can regret that limited “puppet animation” approaches have often been chosen, instead of more advanced solutions. However, the most important and positive aspect of this evolution is that visual culture from any age has remained dynamic in Europe, thanks to the new life provided by movement.

As for humanities, science culture needs to stay alive in the largest community possible. In that, the main contribution of this project was to break down the barriers between researcher, general public and children. All these citizens can certainly not be addressed the same way, but drawing gives them the means to access the same world. This is why it can be considered a common language.

How Citizens benefit

Three kinds of active citizen involvement can be highlighted in this project.

Children were particularly involved between 2006 and 2010, in the context of scientific workshops I had designed. We addressed topics like the movements of cells, the role of the skeleton in movement, life in the Abysses, or agroecological techniques for avoiding plowing. To let children from 6 to 12 years old experiment themselves with the movements of cells, octopuses or earthworms, I created software that facilitates the animation of drawings or modeling clay in a workshop context, thanks to a real-time visualization of the result. The involvement of children convinced me that movement was an excellent entry to addressing more abstract information. I used this experience often afterwards in more large-scale productions.

Researchers contributed actively to the project from 2008 to 2020. At first, they came to me with representation problems that they could not solve alone. They quickly realized that the conception of a drawing was an excellent opportunity to compare the different ways they were looking at the same problems. Today, many of them have integrated such drawing into their scientific representations. This progression led me to develop the concept of “Globule”, an illustrated story based on immune cells that can be extended to other topics and make the world of cells accessible to teenagers.

Finally, my collaboration with researchers became so productive that I was invited to work directly in the laboratories to prepare a PhD, at first in a cell biology team of Institut Curie, and then in a computer graphics team at Ecole Polytechnique. This opened the way to new activities: I co-organized a drawing workshop for cell biologists at the Muséum national d'histoire Naturelle in Paris, and I created a course for young engineers. Thus, the project achieved a real mobilization in the scientific community, beyond the limits of their own disciplines.

Innovative character

In recent decades, a disconnection between reality and the digital world has occurred. The innovative character of this project was to reconstitute, maintain and extend the chain that goes from sketches on real paper, to installations using advanced technologies.

Morphing animation emerged as the missing link between the materiality of drawing, and the spatiality and fluidity of 3D images. At the basic level, morphing creates a continuous transition between two images. With the developments I introduced, this could be used in many ways: displaying drawing with stereoscopy, generating a large number of animal figures on the basis of a limited set, mapping an animated drawing onto an object…

Thanks to this general approach, drawing could be used for the generation of immersive landscapes, to give the feeling of flying over a sea or a forest with a watercolor aesthetic. Such animations are interesting for science as well as fiction: in 2014, they were integrated in the musical for children “Peter Pan” (Guy Grimberg, 1 million spectators).

Collaboration between drawing and other scientific images also became possible. Indeed, many scientific studies use 3D data today, but they are less easy to understand than scientific photographs. In both cases, animated drawing makes them far more accessible, as demonstrated by two short films about heritage and ancient material sciences (“the mystery of the amulet”, “à la découverte des tissus minéralisés”).

Today, with the addition of Artificial Intelligence, this work can provide a valuable basis for a new step in the development of European animation. It also demonstrates a route for innovations in pedagogy: in schools, the book “les lunettes à voir le squelette” (“glasses for seeing skeletons”) can be enhanced by the presentation of anatomical animations, opening up a discussion on evolution. This shows the importance of coordinating both the technical and pedagogical dimensions at a European level.