Suelchen Church Bishop‘s Burial Vault

Basic information

Project Title

Full project title

Category

Project Description

Excavations inside the Suelchen church revealed the remains of previous churches and 15 centuries of burial culture. To replace the existing bishops’ burial vault, the cavity was then occupied by an earth monolith. Eextractions from the monolith form the spaces. The centre is the oratory, housing the burial vault. Rammed earth construction reuses the 1500-year-old cemetery earth from within the church. This transformation goes along with the Christian ideals of the cycle of life and death.

Project Region

EU Programme or fund

Description of the project

Summary

The task was to replace and expand the existing bishop’s burial vault inside the Suelchen Church near Rottenburg am Neckar, Germany. The current church was constructed between 1447 and 1454 in the Late Gothic style. During excavations, fundaments of a pre-romanesque church with a triple-apsed choir dating from the ninth century were found and remains of another church, from the sixth or seventh century, are believed to lie beneath. From a cultural-historical and archaeological point of view, the finds are of paramount importance. During the process of the archaeological excavations the floor of the current church was removed in layers, uncovering relics of more than 1500 years of burial culture in central Europe. The cavity created by the excavations is then occupied by a monolithic volume, forming a link for the new foundation to the existing nave. Our scheme has adopted the underlying axial symmetry from the late gothic church building. The new spaces are depicted as extractions from the overall monolithic structure. A central stairway links the upper church to the lower. The focal point of the complex is a tall room: the oratory, the flanks of which house the burial vault. The archaeological excavations are accessed via a landing, two alcoves in the monolithic volume support the exhibition of smaller artefacts. The entire design contains an intricate system as combinatorics of mathematical ratios, proportions and symbols. All rooms – floor, walls and ceiling - were built using rammed earth, thus transforming the more than 1500-year-old cemetery earth from within the church, which was recovered during the excavations. The transformation and reuse of the earth originating from the same place goes hand in hand with the Christian ideals the cycle of life and death, namely in the book of Genesis 3:19: "By the sweat of your brow you will eat your food until you return to the ground, since from it you were taken; for dust you are and to dust you will return."

Key objectives for sustainability

To justify the incredible efforts to create buildings the central component of sustainable concepts must be the longevity of these constructions. Continuing the work of the builders before us, the project is laid out for the burial of 19 future generations of bishops and is expected to be used for a minimum of another 3 centuries. An integral part to the design process was the development of construction methods and materials that last, age beautifully, gain character and are easily repaired. The technique of rammed earth opens possibilities to plan in lifecycles of centuries, not decades. Due to the geological properties of the site there was a minimal need for structural components made out of concrete to ensure an earthquake-proof structure. Carefully crafted details connect the processed soil to stone and brass. The material property of rammed earth, namely its hygroscopic nature, drastically reduces the need for technical components, like ventilation and moisture regulation, and thus the probability of technical failure.

Since the rammed earth construction method doesn’t need additions like cement or glue it can safely be returned to the soil after the building has served its purpose and perfectly fulfils the criteria of the cyclical ideology of “cradle to cradle”: The historical soil from within the church is removed by the archaeological excavations, processed, transformed, and put back in place as floors, walls and ceilings until its no longer needed. During the construction phase the excavated material was stored, sifted, remixed, and tested 50 meters from the building site. The mechanical process of preparing the construction material doesn’t involve any thermal processing unlike cement or brick. The procedure drastically reduces primary and transport-related emissions.

During that whole time, the builders worked, ate, and slept right next to the site to further reduce CO2-emissions.

Key objectives for aesthetics and quality

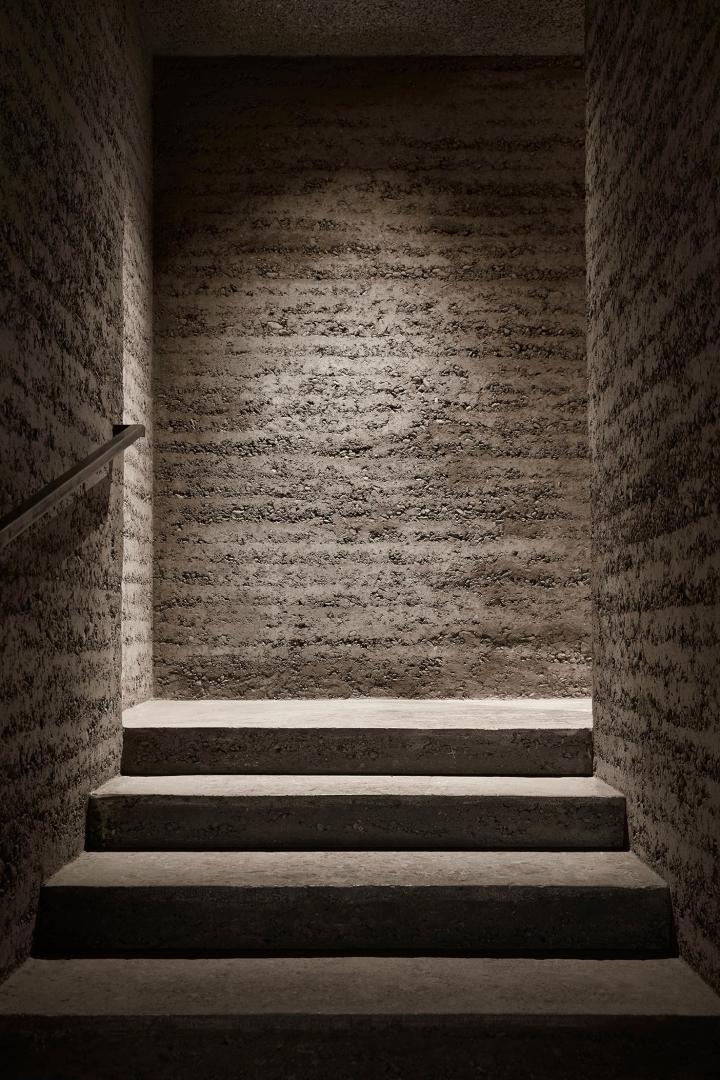

The topic of the end of a life is difficult to frame. There is no exit, no belongings. There is only trust in what is and the believe in what may come. Hoping to be at peace with what was when life ends. The project answers with a perfect balance in radical symmetry. A central stair in the nave leads down towards two sets of stairs that diverge and come together once more. Their slope becomes flatter the further down one proceeds, slowing the pace and making the descent more comfortable. They lead towards a final room - the oratory. A reduced space with a central source of light focusing a monolithic travertine block – the altar, a symbol for Jesus Christ. It reflects the light onto the tombstone of black slate inlaid into the surrounding walls containing the bishop’s tombs. The golden engravings of their names, births, terms of office and deaths shimmer in the half-light.

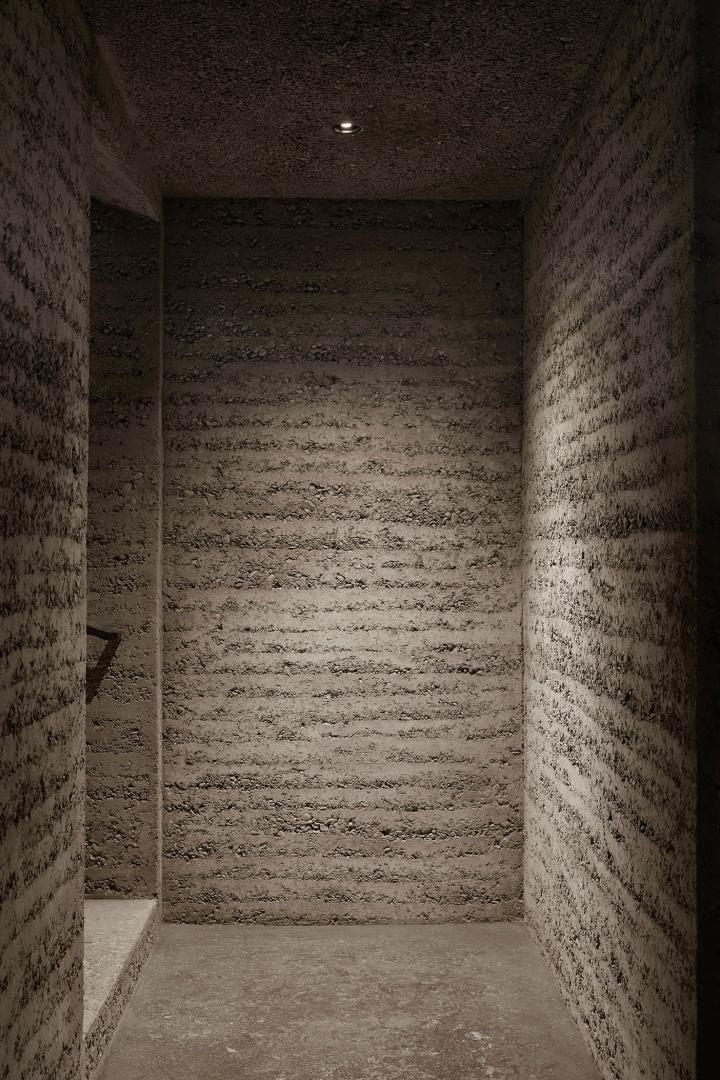

The radical monolithic construction for floors, walls and ceiling in rammed earth is reminiscent of early cave tombs or the monolithic cave churches of Lalibela in Ethiopia. It feels as if the spaces and passages were carved out of the earth and creates an almost mythological underground space. The layering of the construction method reminds of archaeological or tectonical formations that carry the history of the place and creates a feeling of timelessness.

On the other side of the project is an underground exhibition site. A distinct step out of the monolithic volume puts one into a very real place showing the remains of the old churches underneath the current one. The history of the place becomes very concrete and exists right in front of the eyes.

Reduced to space, construction, geometry, light and material, the project emphasizes an atmosphere of concentration, focus and overall silence. Everything is just what it is. It is only through their relationship to one another and the perception by a human being that the surroundings become more than they are.

Key objectives for inclusion

Due to the underground nature of the project and its existing surroundings it is not accessible in a wheelchair. Nevertheless, inclusion played an integral part during the design of the burial vault and the exhibition space. The overall concept is based on a wholistic idea. The quality of the space is created by experiencing it with multiple senses. Since it is pure in construction there is no altering of sounds with additional measures, so the spaces sound the way they are. The surfaces offer a variety of different haptical qualities – the roughness of the rammed walls, the clarity of the brass handrails, the smoothness of the slate tomb stones. The richness of the sensual experience integrates into the inclusive concept of the space. Since the central purpose of the space is primarily felt, not understood it can be experienced even with limitations to the senses.

To allow for prayers and songs the oratory offers the possibility to increase light intensities.

The central way of learning the facts and history of the space is through the guided exhibition. A multimedia presentation with visual and acoustic storytelling gives insight to the ruins’ story. This multisensual communication allows visually or hearing impaired people to understand their surroundings.

Results in relation to category

The project is developed with the understanding, that we are a part of the history of our built environment, that we continue to shape. The concept is deeply focused on what is there and how we can add to and transform these surroundings to fit the current needs. It tries to find the essence of the place and continue the building in that spirit, not contrast it.

At the core of the task of the burial vault lies the cycle of becoming and passing away. Most cultures have created rituals around mourning, remembering, and moving on from those that passed away. The need for a place to bury the deceased is an existential part of human civilization. When we were tasked with the replacement and extension of the old bishops’ burial vault, there was already an ongoing archaeological excavation inside the existing church. Luckily the soil, that had been removed so far was stored right next to the church. After almost two more years of excavation, the same soil, that served as a last resting place for more than 200 bodies was returned in the form of rammed earth construction to form another burial place. When this space has served its’ purpose, it can be taken down and returned as soil once more and thus close the cycle of becoming and passing away: Earth to earth, ashes to ashes, dust to dust.

How Citizens benefit

While the craftsmen involved in the project were mainly from the direct vicinity - e.g. the mason that created the altar, was the latest in a generation of masons, that made the tombstones for the graveyard - the major emotional involvement of the citizens was the importance of the archaeological excavation. The findings show the Christianisation of the area in south-west Germany around the 6th century, at a much earlier time than expected, giving new relevance and pride to the rather young diocese of Rottenburg-Stuttgart founded in 1828. The findings can be seen as part of the exhibition inside the new burial vault that was curated with a team of local historians, local archaeologists, exhibition and media specialists and architects.

Innovative character

The bishops' burial vault is one of few contemporary projects around the world using rammed earth as a primary technique of construction. Apart from the substantive value of the material, it stands in line with a few other projects that lay the groundwork to lift rammed earth constructions into the realm of popular construction materials like concrete, metal, or brick. Rammed earth is a true sustainable alternative to those methods as described in the sustainability paragraph. These projects lay the groundwork for the development of prototypical details and building components of that technique. The project was the first to integrate a rammed earth ceiling successfully.

An indispensable part of the development was the early integration of craftsmen into the process. Only the continued cooperation of architects and expert craftsmen at eye level – especially the expertise of Martin Rauch concerning rammed earth construction - and the client’s will to support that procedure ensured the success and innovative nature of the project.