Nationalmuseum

Basic information

Project Title

Full project title

Category

Project Description

Sweden’s first and foremost art museum have reclaimed its architectural qualities that had been hidden for almost a century. This was possible by numerous innovative technical and architectural solutions that also introduced new features to the 19th century building.

Project Region

EU Programme or fund

Description of the project

Summary

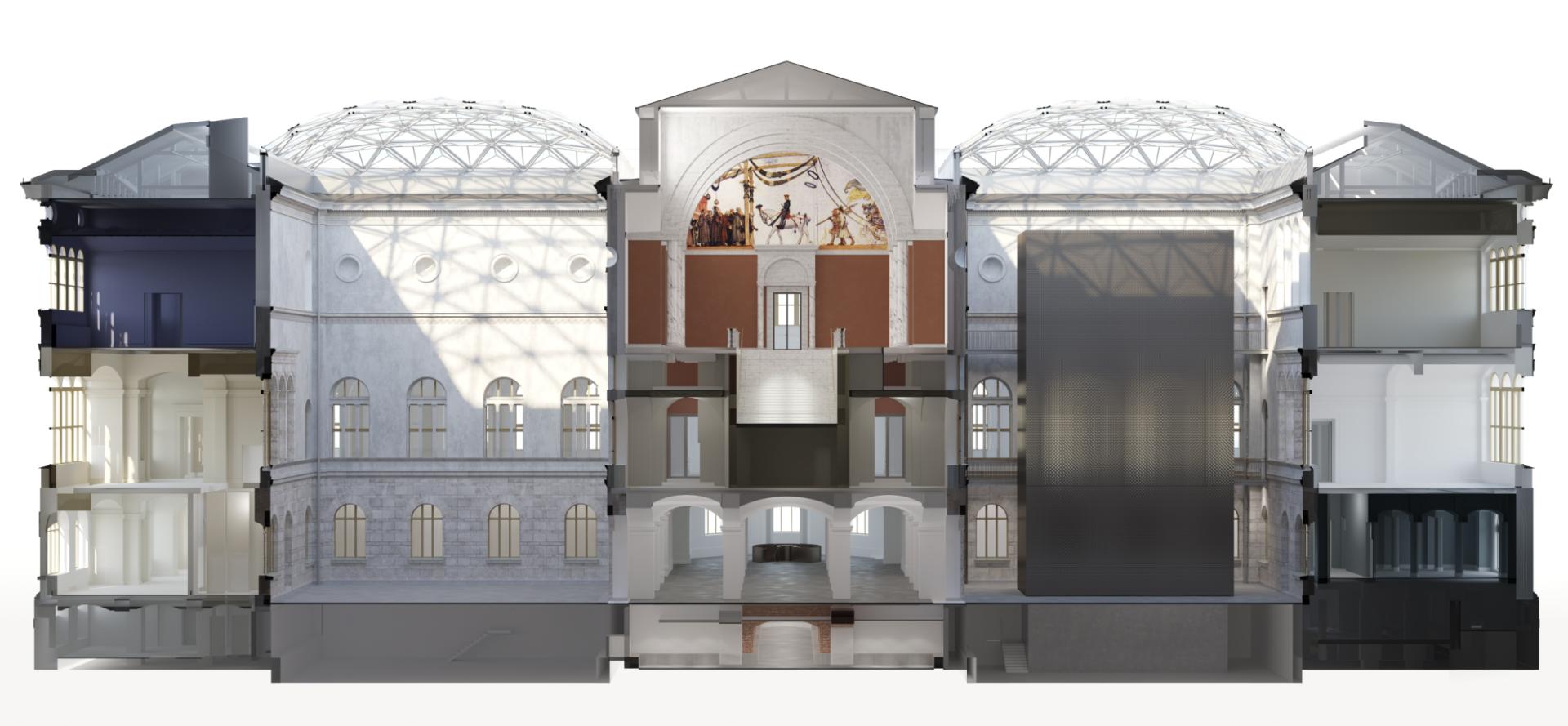

Nationalmusuem in the middle of Stockholm was built after the design of Friedrich August Stüler from Berlin and opened in 1866. A row of changes has been forced to the building since; In the 1910s a series of cabinets were replaced by a large hall, in the 1930s electricity closed almost every window and in the 1960s one of the two courtyards were destroyed and the central hall reduced in height. Contemporary requirements for indoor climate in museums also made large parts of the building unsuitable for paintings.

All technical systems have now been invisibly replaced, and the visitors are as originally intended able to enjoy the view of the environment and the art in combination. The qualities of the 19th century as transparency, vistas and variation do once again meet the visitors. The lost courtyard is reconstructed and equipped with an acoustically inventive glass roof. Statens Fastighetsverk (SFV) The National Property Board, were in charge for the project. Wingårdh architects in collaboration with Wikerstål arkitekter were the architects.

Key objectives for sustainability

The project brief was to create an enduringly functional museum by

reclaiming opportunities for daylight and views to the exterior;

reclaiming for public use several areas that had previously been used for internal activities;

improving the logistics through alternative circulation patterns for the public and separate and secure routes for the art;

replacing and augmenting all technical systems—the middle level had no climate control system at all and the upper level needed a new one; and

achieving all these enhancements with respectful consideration for the building’s architecture and cultural historical value.

The work with Nationalmuseum has oscillated between identifying self-evident opportunities and discovering unexpected ones, though the self-evident dominated the design. Most of Nationalmuseum’s new design is derived from the painstaking work of the building’s original architect, Friedrich August Stüler, and the lion’s share of the architect’s work has been to ensure we meet the new technical and operational requirements while remaining true to the building’s own inherent qualities.

Retrofitting the windows with the most appropriate technology, new inventive glass roofs and an ingenious ventilation system did not only reduce the need for energy, but doubled the capacity of the building. This means, that the climatic impact per visitor have cut by half.

Key objectives for aesthetics and quality

The most stunning improvments in terms of aesthetics and quality of experience beyond functionality regards the courtyards. The Southern Courtyard next to the Entrance hall has been recreated. The limestone friezes previously built into the masonry were replaced with stucco replicas with painted veining, while the original rendering was covered with a thin layer of acoustic render. The goal was to create a replica, allowing the added lift shaft to engage with an 1860s setting. The woven brass of the elevator tower refers to the wickerwork, in which the architect and writer Gottfried Semper saw the origins of the wall, or “enclosure”.

The glass roofs are the second major addition to the courtyards. An inventive construction scatters the echo, thus make the sound behave more like in an open courtyard than in a covered one. But the design improves the aesthetic qualities of the building at large. Their geometrical structure resembles the ornaments of the 19th century, but is undispuitable contemporary at the same time. They did immedeatly gain an emblematic status together with the elevator tower in wowen brass. A signature for the new Nationalmuseum.

Key objectives for inclusion

SFV created an in-house group of specialists – project manager, architects, engineers, building conservationists and procurement officers – whose first task was to contract a team of consultants capable of undertaking this demanding assignment. Based on the conservation program and the Museum’s vision and requirements, tender documents were prepared for a feasibility study.

An initial step was to arrange three knowledge seminars for the entire feasibility study team. The feasibility study showed that a renovation and remodeling project meeting the exacting requirements set was possible. One of the guiding principles was to create as much public space as possible, both for displays and exhibitions and for visitor services. It was also noted that, thanks to modern glass technology capable of filtering out harmful radiation, daylight could be reintroduced to the building without damaging the objects on display. In addition, the study proposed opening up the South Courtyard again and having an underground building for the climate control plant in the park, combined with an extension providing a secure loading facility and a new, large lift. Without far-reaching cooperation between SFV and the Museum, this degree of consensus could not have been achieved.

The success of the New Nationalmuseum can be measured in terms of visitors. The first year after the reopening did the museum host three times as many visitors as an average year before. The restoration did not only attract former fans of the museum to its venue, but more important many new groups as well.

Results in relation to category

In a time when costly public works often are questioned, Nationalmuseum's restoration is a marvelous example of how a carefully executed work on all levels - from planning to construction - can gain a very warm response from all citizens. The creation Nationalmuseum was a trailblazer for public institutions in the middle of the 19th century. Today, its restoration have opened up a common understanding for the need to handle the heritage with both care and dare! The large elevator tower has not only made the building much more accessible. It is also a bespoken item for the new museum, and a popular backdrop for lectures, meetings and even weddings. The new Nationalmuseum has become a vibrant space and a vivid example of our heritage's impact in Europe's transition to sustainability.

How Citizens benefit

The restoration of Nationalmuseum was one of the largest project ever executed by the National Property Board. The planning process included years of feasibility studies and a dialogue process with the government, as the project was fully paid by governmental taxes*. Hence, the communication with the citizens was also an important factor of the success. no efforts was spared to show and tell what the citizens would get for their money.

(* That the restoration was entirely paid by the government is not completely true. During one of the public shows of the ongoing work, one lady asked the guide if all the ceilings were to be repainted in the 19th century manner. "Unfortunatly not", the guide told her. "There is no money for that". The lady sighed, and a week later she sent the National Property Board a letter: "Please paint the ceilings. I'll pay!")

Innovative character

The glass roofs of the courtyards are innovations that deal with the fact that most courtyards covered with vaulted glass have terrible acoustics. These roofs are essentially domes too, with a rise of 2.5 metres, resting on squares. Each dome consists of 104 triangles, and because each triangle is covered by a tetrahedron of glass, the roofs scatter the echo, primarily to the parts of the courtyards that are finished with a sound-absorbing acoustic render. The intricate geometrical pattern, with its many nodes, have decorative qualities that can rival the 19th century decoration of the museum, but was merely designed to make the echo disappear and the steel supports as slender as possible.

The glass over the courtyards has coatings that mean that it blocks both incoming sunlight and losses of heat. The roofs are thus very well insulated. The U-value of 0.5 is more than twice as good as that of regular triple-glazed windows. In addition, the glass blocks 81 per cent of the heat from incoming solar radiation and transmits only 38 per cent of daylight.

The new ceiling rosettes are another innovative feature in the project. They combine modern technology with traditional craftsmanship, enabling some of the biggest technical improvements of the renovation to remain almost invisible. Based on originals, new plaster rosettes were cast and fitted with sprinklers and ventilation diffusers. They were then painted with distemper in colours similar to the original ones.