Climate Park Copenhagen

Basic information

Project Title

Full project title

Category

Project Description

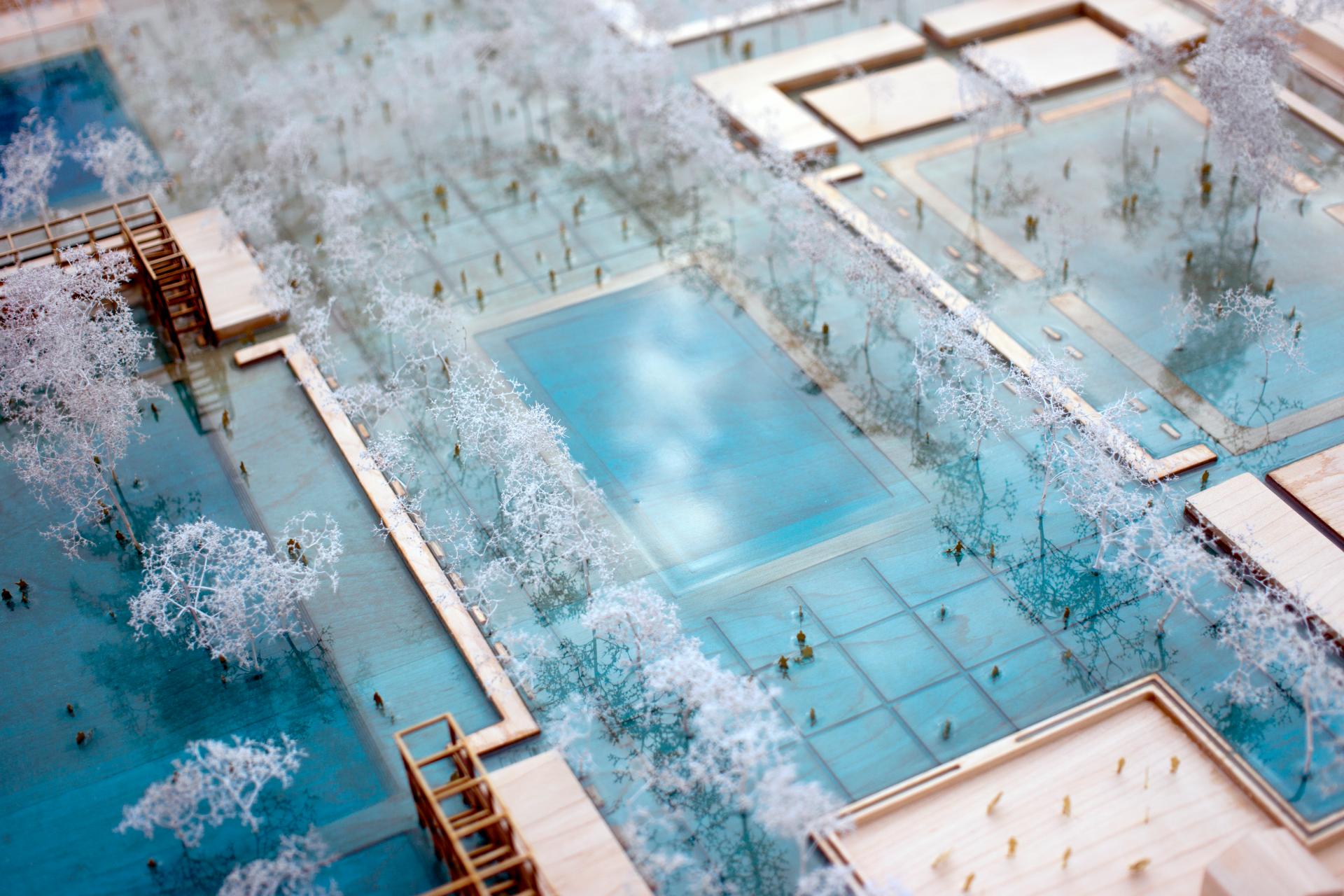

The innovative Climate Park in Copenhagen has been thoroughly transformed and is now the largest climate capacity project in Copenhagen. With 22.600 m3 extreme rain capacity, the park both mitigates the impact of the climate crisis and delivers new circular, recreational, and sensory opportunities for the public. The strength lies in the respectful integration of the massive water volume into the park’s classical DNA and the project is thus the very first of its kind and could inspire any city.

Geographical Scope

Project Region

Urban or rural issues

Physical or other transformations

EU Programme or fund

Which funds

Description of the project

Summary

The historical Enghave Park, with some of Arne Jacobsen’s early designs, has been respectfully transformed and is now the largest realised climate project in Copenhagen. With a 22.600 cubic meters (6 million gallons) extreme rain water capacity the park answers the need to handle future water challenges. The challenges are positively transformed into a large variety of new circular, recreational, relaxation and sensory opportunities to be used both in an everyday situation and in the event of cloudburst.

The water is visibly and innovatively handled in the project using multifunctional cloudburst pools and a 550 m encircling 'water wall' that also features seating and play possibilities. The solutions hold back the extreme rain and at the same time create new living, sensory and recreative opportunities for everyday life. The new circular functionality in the park also features a 2-million-liter rainwater reservoir that harvest the cleanest fraction of urban water from the city’s roofs and use it for its recreational features, for irrigation of the parks’ plants and lastly it provides service water for the city’s utility trucks at a water tanking spot at the edge of the park.

The listed park has been transformed into a climate project with a water reservoir for extreme amounts of rainwater. The transformation of the park has turned the water challenges to a variety of new experiences for recreation and interaction and creating climate awareness in a subtle and positivistic way.

The strength of the project lies in the integration of the huge volume of water into the park’s neoclassical aesthetic and the project is thus the very first of its kind. The architects show that we can both preserve and rethink our common cultural heritage when the climate crisis hits the cities. And that we can positively involve more than 1 million annual visitors in a reflection on our collective impact on the planet through just one public park.

Key objectives for sustainability

The 550 m water wall establishes the largest reservoir in the surface water management in the park and it is only supposed to function in extreme cases of flooding - i.e. 100 year rain events. At extreme cloudbursts, the gates in the wall will automatically be raised and the park will be filled with water. In the daily use the water will tell the story of the Climate Park and the water will be a recreational and educational element. The daily rain will be collected in the underground reservoir under the Rose garden, filtered and reused for recreative purpose in a trench at the top of the wall encircling the entire park. The water is visual in all spaces and will communicate the important message of climate change.

The Enghave Park is also a green breathing space for people and animals. 83 new trees have been planted in the park, spread across 10 different varieties. Most are planted in connection with the re-establishment of the alleys. The biodiversity in the garden is further enhanced by the 11,000 perennial plants, consisting of 55 different varieties in the Library Garden as well as 950 fragrant roses planted in the Rose Garden. All over the park 220,000 flower bulbs have been planted, which together with the rest of the planting will help make the park attractive to the eye and mind all year and create habitats for urban wildlife as insects and small animals.

By fusing water technology, cultural and social gatherings as well as including biomass and -diversity we hope to further the cognitive shift that is needed to better understand the impact of the climate crisis. And how we better can establish and further a more appropriate and informed behaviour daily. Circularity is not only a technocratic and quantifiable paradigm, but also a fundamental change in our culture, that architecture and technology should promote. We believe the Climate Park pays tribute to this new emergent agenda, and establishes a new circular awareness and culture in Copenhagen.

Key objectives for aesthetics and quality

Enghave Park has been an important recreative space at Vesterbro for more than 90 years. A respite for the working class living in the neighbourhood. The park is built as a strict neoclassical park with a reflecting pool, geometric axes, playground, and stage. With the challenges like rising population growth and more frequent cloudburst, there is a need to rethink our urban spaces smarter and more multifunctional. T

The extreme climate impact on our historically sensitive cities demands adaptive and innovative architectural approaches. Our design for The Enghave Climate Park implies, that great innovations reach as deep into our cultural and historical roots as much as they point towards the future.

A key objective was to let our new design ‘breathe’ through the original design dna and ethos in the park, and to use the necessary investment in resiliency to radically boost the liveable parameters of the park. The extreme rain functionality will only be active in less than 1% of the time so we have been focusing on how the public investment could promote liveability and circularity on a daily basis:

- A circular and surface bases solution makes for a gentler impact on existing heritage fabric. The small footprint preserves trees and have a small visual presence, yet a large capacity of almost 23.000 cubic meters.

- Surface based design uses way less resources than underground reservoirs. The water wall concept we have developed can be applied to almost any open space and is very effective and requires only little investment.

- Underground reservoir capacity for 2 million litres of harvested rainwater to be recirculated in the park.

- Focus on added biodiversity and endemic plant species that support wildlife and insects.

- Robust and very durable materials used everywhere to last practically forever – the park is expected to be preserved as cultural heritage indefinitely.

Key objectives for inclusion

- The transformation process has been very thorough regarding public participation and engagement.

- Municipal driven renewal office to frame the project before the architecture competition

- Cross disciplinary design teams to enter competition with specific competences on public engagement.

- Co-design workshops with citizens after competition on the specifics of the design and functionality.

- New entrance to the park towards library/public building that promote synergy.

- A school opposite the park uses the park as an extended school yard.

- Skating rink integrated into the central stage area makes for sustainable use of the winter city.

- Arne Jacobsen’s pavilions rebuilt to house communities (currently a petanque/boules club lends one of them and the other is planned for social non-profit café).

- The classicist formal design has been upgraded to promote social encounters and health-related activities.

- Water wall barrier is designed with benches and playful water features.

- One of the large water reservoir doubles as a state-of-the-art inline hockey-court with multi functionality for urban sports, public events.

- Open 24/7/265 for free for everyone.

- Fully accessible for everyone through universal design.

- A variety of spaces to facilitate both active and reflective calm places.

Results in relation to category

The everyday rain from the roofs of the new neighbouring district the ‘Carlsberg City’ will be directed to Enghave Park and be collected in a 2-million-liter underground reservoir. The collected rainwater will be used for the city’s utility trucks, for watering the trees and plantation and lastly, it will be used recreatively in the park’s water features, like the water wall and the central fountain garden where kids are invited to play. The recycling of rainwater will save millions of liters annually of clean drinking water annually and is a shift in practice in Copenhagen.

Denmark have traditionally relied on the use of groundwater, and this is the first time in the history of Copenhagen where rainwater is being harvested and used recreatively. The harvested water will pass a 3-stage cleaning process in the park that cleans it to the highest possible standard. As nations face more and more problems with the urban and agricultural pollution of groundwater resources, this circular approach is a solution to work safely with the resources at hand and using them locally and visibly.

On a expanded note, the use of the available resource of rain water creates a new dimension of climate awareness in the park. One consequence of the climate crisis is obviously too much water. But another often overlooked similar threat to the liveable city, is extreme periods of heat and drought. We are only using the harvested rain water in the park. If longer period of drought happens, the park will focus its water usage on only critical functions, like preserving the park's biodiversity, while other funtions like fountains etc. will be stopped as long as the water is scarce. This fundamentally involves the users in a bodily relatable experience of the urban metabolism and invites them into reflections about circulairty and climate awareness.

How Citizens benefit

This particular district of Copenhagen have always been signified by the working class spirit and still today there is a powerful public voice that demand inclusivity and diversity. The park’s transformation has been initiated by the City of Copenhagen. A local ‘area renewal’ office was established in the library and culture house in the adjacent street directly outside the park. In this way there has been a very early dialogue with the community, and workshops as well as analysis and early concepts have been proofed by the community. Thus, the brief for the design competition was largely based on year long research and information accumulated at the ‘renewal office’. We were given several reports containing detailed research data on how the users would use the park, how they perceived the many different spaces and how they could imagine the future of the park.

Our team was cross-disciplinary, and worked closely with the office called Platant to facilitate the user involvement process. We had several public events during the design process and involved both the general park user as well as specific user groups. All public involvement workshops had specific themes and several of the final design elements and solutions have been tested live before we finalized the design. and technology and the school kids were a great resource in giving interesting ideas, as well as putting the climate crisis on the agenda in a very concrete and positivistic manner.

Two shipping containers were put in place temporarily for testing out a café function at the main entrance of the park. This phase was during the Syrian crisis, and refugees were invited in helping out running the café, effectively welcoming them to Danish culture. Another example is when school kids were involved in creating new ideas for the water wall. That element was integrated in longer spanning learning segment about innovation and circularity at the school.

Physical or other transformations

Innovative character

- Working with a circular approach that harvest rainwater locally and use it for a variety of purposes is sustainable and not something that is mainstream in nations like Denmark that almost entirely rely on the use of pumped groundwater.

- Traditionally engineers and municipalities have been managing rainwater underground to a large extent, but due to the extreme nature of our new climate reality, with more frequent and violent rain events, this practice is not flexible enough, and results in flooding. Adding reservoir capacity to mitigate this new reality is a mainsteam practice, but due to the lack of free real estate in dense cities and the very expensive nature of this practice, the implementation is too slow.

- Working with surface based solutions and allowing controlled flooding of our free areas are a very resilient, low cost and low impact approach with very high hydraulic capacity.

- This approach of 'co-existing' with water and our new climate situation can be scaled to almost any global context and both make for more secure and resilient cities, but also do it in a way that is much cheaper and flexible than current practices. Allowing for controlled flooding is an integrated aspect of the sponge city. Our approach show it can be done with minimum impact in a highly sensitive context and be build on top of cultural heritage - something that is often overlooked when talking about the future of city. The reality is, that most of the future city will very much so be tied together with the genious loci and the given site condisions of of the historic urban fabric.

Learning transferred to other parties

Most great design innovation and most great architecture seems child like simple once you understand it. When we were initially presented with the catch-22 task of turning the park into a large scale hydraulic volume, and being expected to preserve both the parks cultural heritage and existing nature, we were struggling to move forward. Only by working truly cross disciplinary on the design team combining architecture, engineering and public involvement, could we come up with the solutions that could win the competition and be implemented accordingly.

But the exemplary capacity of the project extends further than just great design, engineering and user involvement. The competition brief in itself represents a great achievement within co-creation and cross disciplinary development of the city. The municipality's ability to co-fund and co-develop projects with the city's utility company Hofor is a first for Copenhagen at that time, and is a model any city could learn from. The necessary investments of future cities into public space is monumental, and all stakeholders should be able to co-create and co-fund these investments.

Lastly, the establishment of a local area renewal office to give space for all voices to be hears prior and during a transformation of this scale is the very foundation this project stands on. If we are to fully succeed with the green transition the city's users needs to be heard. True liveability and true life-cycle awareness can only be founded on true and ongoing involvement of the public. The sense of involvement and ownership from the local community we now see surrounding the finalized project is very much a testiment to the early phases of the transformation. This should serve as an inspiration to all urban transformation and renewal.