The Atlas of Emptiness

Basic information

Project Title

Full project title

Category

Project Description

Libavsko is a part of the hills of northern Moravia. The landscape of fields and windmills, nurtured for centuries, has gone through a complex history that resulted in the post-war displacement of the vast majority of the locals. They were replaced by people for whom the landscape never really became home. The decaying villages and fields reflect the fate of the Sudetenland, whose problems still affect our society. We can learn a lot about ourselves on a journey through the Atlas of Emptiness.

Geographical Scope

Project Region

Urban or rural issues

Physical or other transformations

EU Programme or fund

Which funds

Description of the project

Summary

The characteristics of rural areas vary from region to region, but few regions are as specific as Libavsko, where the problems caused by the social and environmental changes of the 20th century Czechoslovakia have accumulated into a particularly sad mix. The area was first forcibly depopulated of its native German-speaking population, became a military training area, later occupied by the Soviet army, and suffered neglect by much of society after the revolution. The result is an empty landscape losing its original picturesque character, threatened by drought.

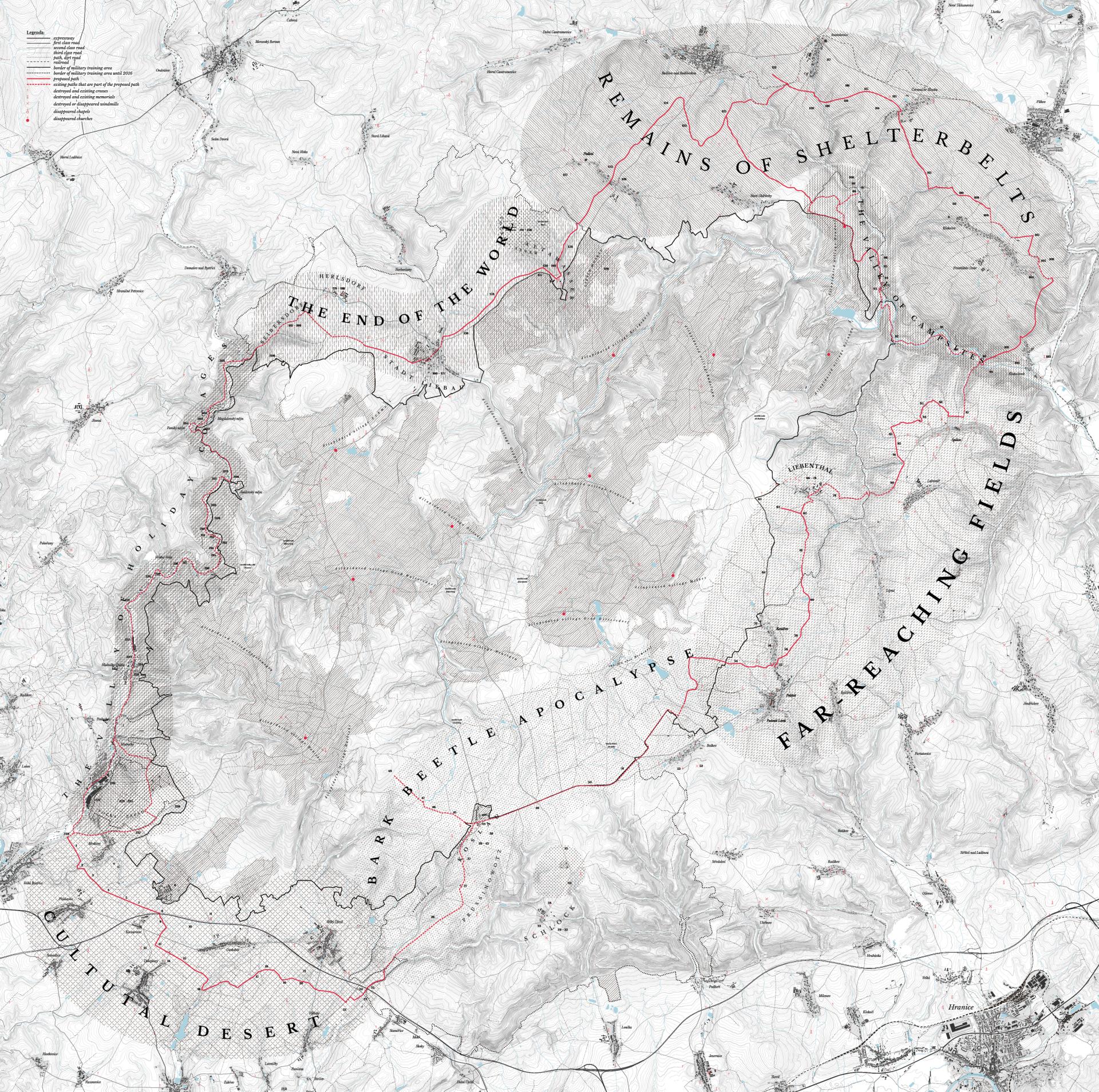

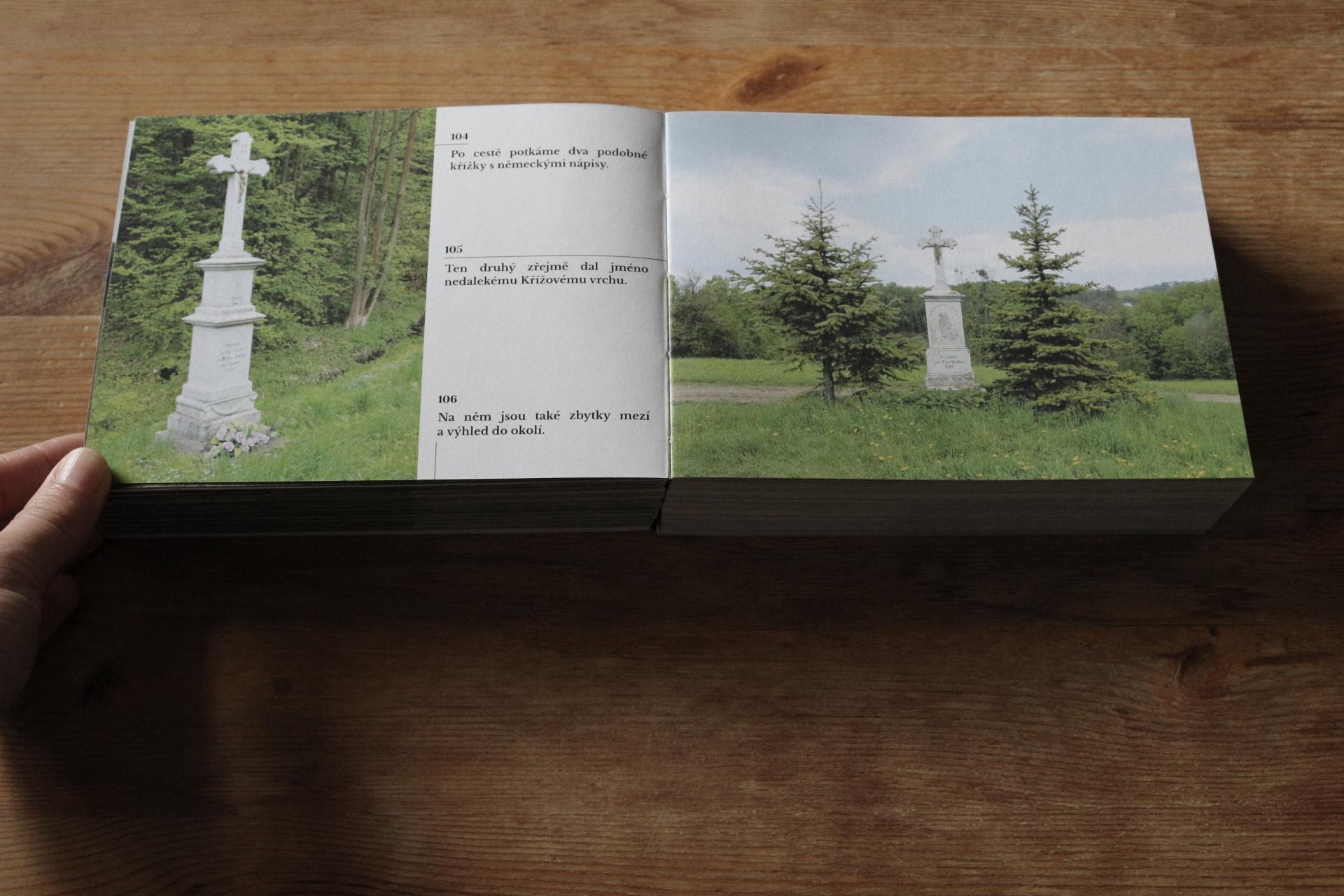

The Atlas of Emptiness works together with three large maps as a guidebook to the vanished paths through the empty landscape around Libavsko. The Atlas sees each of the 240 places connected by this imaginary route as small (and perhaps insignificant) parts of a larger and more important social story, which it introduces us to. The guide adds commentary to each such place, whether it be lonely trees and crosses in fields, ponds and abandoned villages. Everyone can piece together these individual components into a story that has unfolded here in the 80 years since the sad expulsion of the German-speaking inhabitants.

The proposed route passes through a landscape that the guidebook renames according to what it has come to over the years.It begins in the Cultural Desert, continues through sections of the Bark Beetle Apocalypse, Far-Reaching Fields, The Valley of Campsites The Remains of Shelterbelts, The End of the World, and ends with The Valley of Holiday Cottages.

The project aims to open the eyes of anyone who decides to explore this landscape, educate us about the causes and come up with our own creative solutions.

Key objectives for sustainability

The aim of the project is to return a healthy, sustainable landscape to the region and make it accessible to locals. Many of the original features, such as small-scale architecture in the agricultural landscape (columns, crosses, chapels), roads and paths, field divisions and others, were physically destroyed during collectivisation. The places that remain have become inaccessible through the vast fields. In practice, collectivisation made the landscape impenetrable not only to people but also to animals. Disappearing biodiversity, soil erosion, spruce monocultures easily attacked by harmful insects, problems with drought, but also with flooding, are just some of the problems that expropriation and the subsequent insensitive agricultural practices have caused. Not to mention what it has done to society and its continuity.

To this day, we have not come up with workable mechanisms to remedy this long-standing situation. Whether through lack of political will or ignorance, the Czech landscape remains vulnerable. The remedy through subsidy programmes appears to be the most effective for the time being, but its scope is limited and even it does not involve the wider society and its interests so much in the problem. At the same time, reflecting on our history and acknowledging our own mistakes are needed to solve the problem. In order to move forward as a society, we need to have a good understanding of our past. The purpose of the project is to mediate this, to convince society that the state of the landscape is also its heritage and its reflection. In a healthy landscape, plant, human and animal have equal status.

Such landscapes can produce quality food and increase the local availability of products from short supply chains. Without the unnecessary environmental burden of transporting products to distant locations or chemical fertilisers that destroy groundwater and small field animals. In the longer term, the project aims to inspire other regions of Czechia.

Key objectives for aesthetics and quality

Satellite images from around the Czech-Austrian border show that the diversified landscape of small fields and copses is more picturesque and resilient than the landscape of huge and intensively cultivated fields. A healthy landscape is a beautiful landscape. Our society goes to the countryside at every possible opportunity, but few people realise that a few decades ago the landscape looked very different. While continuity remained in Austria, changes took place in Czechoslovakia that completely transformed the landscape. And unfortunately for the worse. Despite popular belief, we have to admit that our landscape does not stand up to the surrounding countries in terms of beauty. However, in archival satellite images taken before and just after the Second World War, we can see that the Czech landscape then was almost completely different from that of Austria, Germany or Poland. Yet few people voluntarily study archival images of the landscape to understand how much the picturesqueness of our landscape has disappeared. Therefore, the Atlas of Emptiness introduces visitors to the past appearance of the landscape. It seeks to engage their own imagination and memory, so that the past appearance of the landscape at least materializes in their minds, and fills in the empty missing places in their living space.

Key objectives for inclusion

The idea of the project is that the wider public (whether from local communities or from other regions) will begin to discover it's own past. To learn from it and translate the new knowledge into the built and natural environment. The aim is to start a debate about what we want our landscape to look like in the future and how to make it sustainable again in the current social conditions.

Until today, this topic has been overlooked in our country. The agricultural landscape, which covers the vast majority of the country's surface area, is operated by a few actors, mostly from among the giant agricultural concerns. They have a very one-sided view of the landscape. Primarily it is a source of income for them, rather than a fragile source of life not only for human society but also for animals. The Atlas of Emptiness wants to convey to people the knowledge that they have the right to shape their environment too - whether by pressuring their local leaders or through citizen activism. The guidebook shows that not all solutions to climate change have to be expensive and technical. Sometimes all it takes is restoring a path, a tree line, a copse or a stream in a field. Sometimes it is enough to make the landscape permeable again - to connect villages with new walking and cycling routes. To help it retain water in the soil to prevent sudden flooding.

The project does not offer a single right solution. It gives communities the freedom to find a solution that suits their circumstances and their lifestyle. At the same time, it gives the freedom to decide what form landscape restoration could take. Whether it would be financial subsidies or joint work efforts in the field or a completely different form according to the creativity of the local people. The aim is a landscape that farmers, local people, landscape experts and other stakeholders work together to achieve.

Physical or other transformations

Innovative character

If we want to achieve a well-kept landscape, it will certainly be beautiful too. If we as a society shape its form, we will feel a strong attachment to it. If the landscapes we manage are functional, they will protect the interests of people and animals.

The landscape is the environment in which we live. Even cities themselves are embedded in the landscape, so nature and society cannot be separated. However, our society has not yet come to the realisation that only a sustainable landscape can provide us with a good quality of life. For now, we remain disconnected from the landscape. Few descendants of farmers who have had their trades confiscated have returned to the lifestyle and farming of their ancestors after restitution. Important knowledge of the local nature has not been passed on to them; the lifestyle has taken them on a different path. Farms began to deteriorate, were demolished or rebuilt beyond recognition. The countryside lost its function and therefore its beauty. It became poorer. The idea of the project is to become aware of this state of affairs and, with a joint effort, to remedy it with creativity.

If such an effort proves useful in the Libavsko area, it may become an inspiration for other, equally affected regions of the Czech Republic.