Away with segregation

Basic information

Project Title

Full project title

Category

Project Description

A community-driven urban design approach to revitalize post-industrial neighbourhoods in the 21st century. The project aims to give municipalities, designers and residents a roadmap for reconnecting and reintegrating degraded industrial districts without triggering unhealthy gentrification. With a focus on the transition to sustainable transit, incremental beautification, and community engagement, our methodology aims to help breathe life back into neglected local communities from the bottom up.

Geographical Scope

Project Region

Urban or rural issues

Physical or other transformations

EU Programme or fund

Which funds

Description of the project

Summary

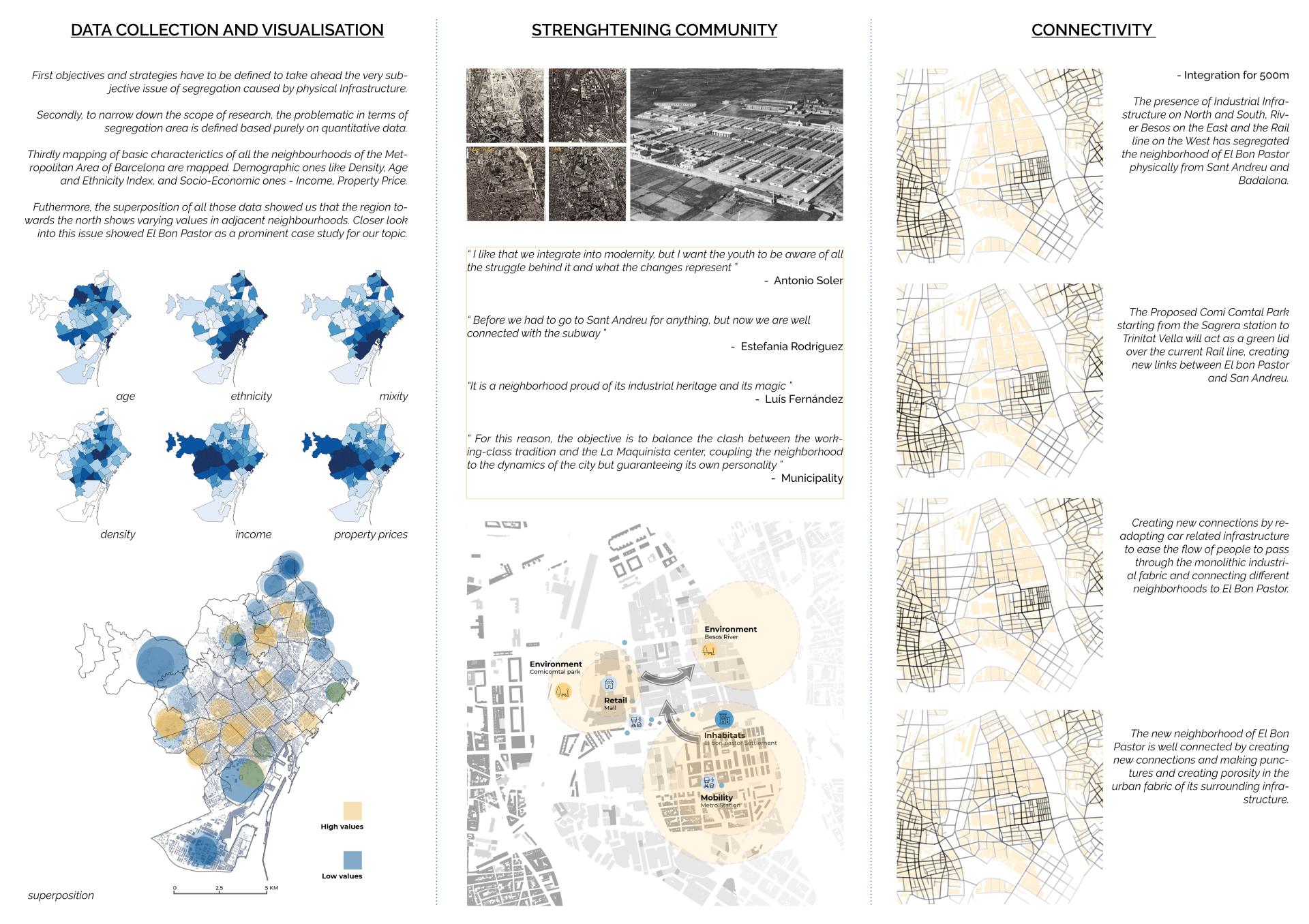

As post-industrial cities have grown up around their heavy industrial infrastructure, once proud blue-collar industrial neighbourhoods have struggled with their identity and place in the modern world. Impenetrable and monolithic blocks act as an architectural tissue of segregation between and inside these urban communities. This context is a background to study and understand, how cultural identity and community engagement can reshape the architectural fabric itself. The proposal entails a system of community-driven architectural integration and connection as an antidote to the disconnection of industrial, car-oriented landscapes. The project presents an adaptive reuse intervention that operates cyclically to generate integration and connection in the urban fabric over time. More specifically, it is a theoretical framework designed to revitalize the disconnected and monolithic, car-oriented neighbourhood of El Bon Pastor in Barcelona. In our design work, we focussed on the small scale and the near term in order to constrain our thesis to the realm of the possible, but ultimately the objective is to catalyse long-term, high integrity change in the urban fabric of such neighbourhoods. The residential town centre of El Bon Pastor is surrounded by a sea of industrial land which segregates it from the city that has grown up around it. Additionally, the city of Barcelona has been on a mission to replace the original, outdated housing stock in the neighbourhood, but lack of local access to the planning process has rekindled decades-old fires of political oppression. Locals are fighting to defend a way of life and a culture that is at risk of becoming a memory due to thoughtless "modern" urban planning. In the project, we worked to simultaneously address the twin problems of architectural segregation caused by automotive infrastructure and heavy industry, and the political conflict caused by lack of local authority in the process of implementing modernization.

Key objectives for sustainability

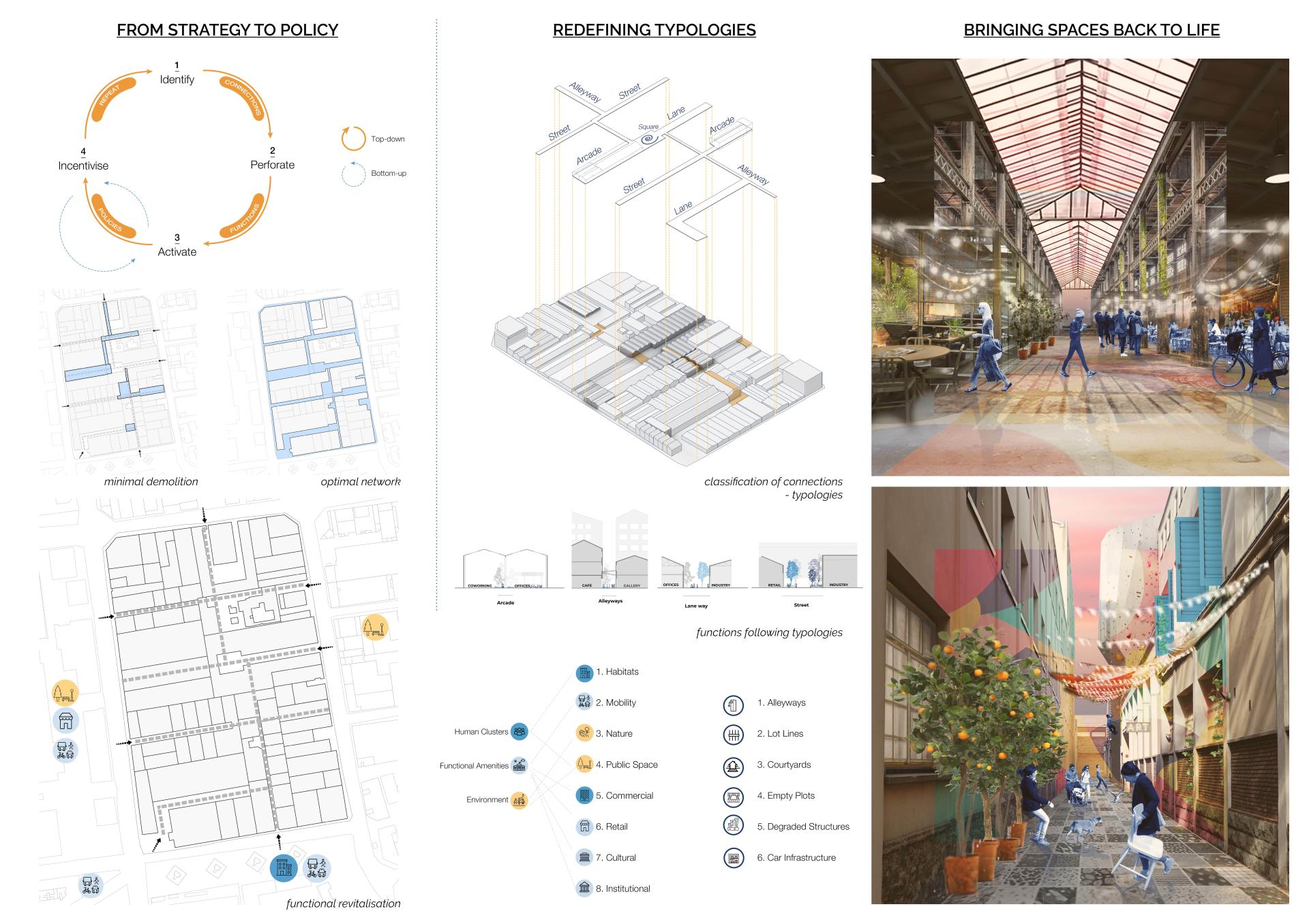

There are two aspects of our project that address circularity and environmental sustainability. First is the context of proposing a neighbourhood without cars. We believe it is particularly important that previously segregated industrial neighbourhoods are revitalized with sustainable mobility at the heart of the design thesis. Not only does this ensure equity of mobility, it also guides the design process towards efficient and thoughtful urban spaces made for people instead of cars. The outcome is a safer and more sustainable urban system that benefits from outdated car-related infrastructure being put to more useful ends. Second are the twin principles of minimum necessary demolition and construction waste up-cycling. Our urban revitalisation cycle requires that certain architectural structures are demolished to make way for much needed pedestrian connections through monolithic industrial blocks. By following the design guideline of minimum necessary demolition, connections can be strategically located as to require only small sections of existing structures to be removed. The construction material obtained through this process can then be up-cycled into new architecture that will inevitably follow in the spaces adjacent to the new connection. These construction activities and the subsequent appreciation of property values they generate, especially in the case of highly degraded buildings, unlock new capital flows which can be directed into making energy efficiency upgrades and funding rooftop solar and urban gardening projects.

Key objectives for aesthetics and quality

The aesthetic experience of a segregated and degraded industrial district is one of the most obvious barriers to renewed community engagement and urban revitalization. Engagement requires a feeling of safety and revitalisation requires a sense of inspiration. As such, our proposal puts special emphasis on beautification and human scale design. The utilitarian, industrial scale architecture has to be scaled down and humanized before it can engender an inviting sense of safety. Beyond that, we feel that community-lead art projects are actually central to the revitalization process and not just a nice after-thought. Designating space for and giving authority to street art is one approach we explore. Street art can humanize the scale and beautify the environment without remaking the architecture itself or requiring any major construction. Additionally, the use of tactical urbanism is key in this regard. It serves to quickly and affordably create an aesthetically welcoming and comfortable streetscape with beautiful furniture, playful lighting, and abundant plant life. The importance of aesthetics is impossible to overstate when we consider that these are often degraded and unwelcoming spaces which have to make a 180 degree transformation without losing their original character.

Key objectives for inclusion

This topic is at the heart of our proposal. Our analysis and observations made clear that this is where most other efforts have fallen short in the El Bon Pastor neighbourhood. Residents have been neglected in the core decision making processes around revitalisation that have occurred over the past few years. Although it may not seem like it on paper, the city's approach to community engagement has often come off to locals as patronising lip service. The obvious tension around "modernization" that has built up in the city's efforts to improve the housing stock make that much clear. Stemming all the way from the neighbourhood's origins as under-serviced workforce housing, the proud blue-collar culture and political energy of the locals is a key factor that presided over our entire analysis process and permeates our proposal through and through. Politically oppressed communities have a way of self-healing through the development of strong community bonds that only grow stronger through periods of political strife. We believe that has been the case in El Bon Pastor, and as such our proposal puts community engagement at the core of the revitalization process. The creation of pedestrian connections through the industrial architecture serves nothing if not to open new space for community actors to engage with. Many methods of implementation were explored in this regard. One such method is to allow organizations such as local schools and small businesses to adopt new spaces as they come online. Formally adopting the space would grant the authority to guide the aesthetics and the programming that may occur in the space as it is absorbed into the community, bringing local ownership into the urban realm. Ultimately the objective is to develop a deep connection to place, such that local residents and organizations engage with the emerging urban environment as it is being created from the ground up.

Physical or other transformations

Innovative character

Sustainability, aesthetics, and inclusion were core principles in our design work. To propose revitalisation without these three principles would be to propose cultural destruction, sweeping gentrification, and extensive reconstruction. We knew our proposal would have to explore mechanisms that bring people and cultural energy into the space without trading one problem for another. The cycle we developed only hopes to achieve that because of its foundations in sustainability, aesthetics, and inclusion as described above. Removing cars in favour of public transit and beautiful safe street systems is an exemplary move in any community striving to be more sustainable. That ties directly into the increased focus on aesthetics that must come in order to revivify degraded and typologically unattractive architectural landscapes. That said, beautification and the journey back to the human scale doesn't have to be expensive. It can be undertaken by local artists and communities making small aesthetic improvements that to add up. And lastly, if the push for revitalization is not generated at the local level, outside forces will only engender resentment. Thus it is critical to start the process by engaging the community in a real conversation about values, objectives, and dreams. Only then will subsequent development and change have the optimal short and long-term outcomes.