Mapping Diversity

Basic information

Project Title

Mapping Diversity

Full project title

Mapping Diversity

Category

Regaining a sense of belonging

Project Description

How can we discuss inclusive cities when most streets are dedicated to men? Committing a road to one person, as opposed to another, implies celebrating all the values associated with them. Research has shown a correlation between a city’s gender bias in street names and cultural factors, like gender equality in that city. Street names are not neutral, and it is time to talk about them so that all citizens feel included and represented by the values that cities celebrate.

Geographical Scope

Cross-border/international

Project Region

CROSS-BORDER/INTERNATIONAL: Italy, Albania

Urban or rural issues

Mainly urban

Physical or other transformations

It refers to other types of transformations (soft investment)

Year

2023

Description of the project

Summary

The names of our streets are not harmless urban elements. They are more than a tool for orienting ourselves in space: they have strong symbolic power, and they are permeated with the cultural values behind the decision-making processes, the legitimation of the past, and the construction of a collective historical memory of that past. It is no coincidence that from the French Revolution to the Black Lives Matter protests, political demands for change have been accompanied by moments of symbolism that have often involved the renaming of streets, squares, and other urban spaces. This begs the question: in the onomastics of contemporary Europe, who is visible and who remains invisible?

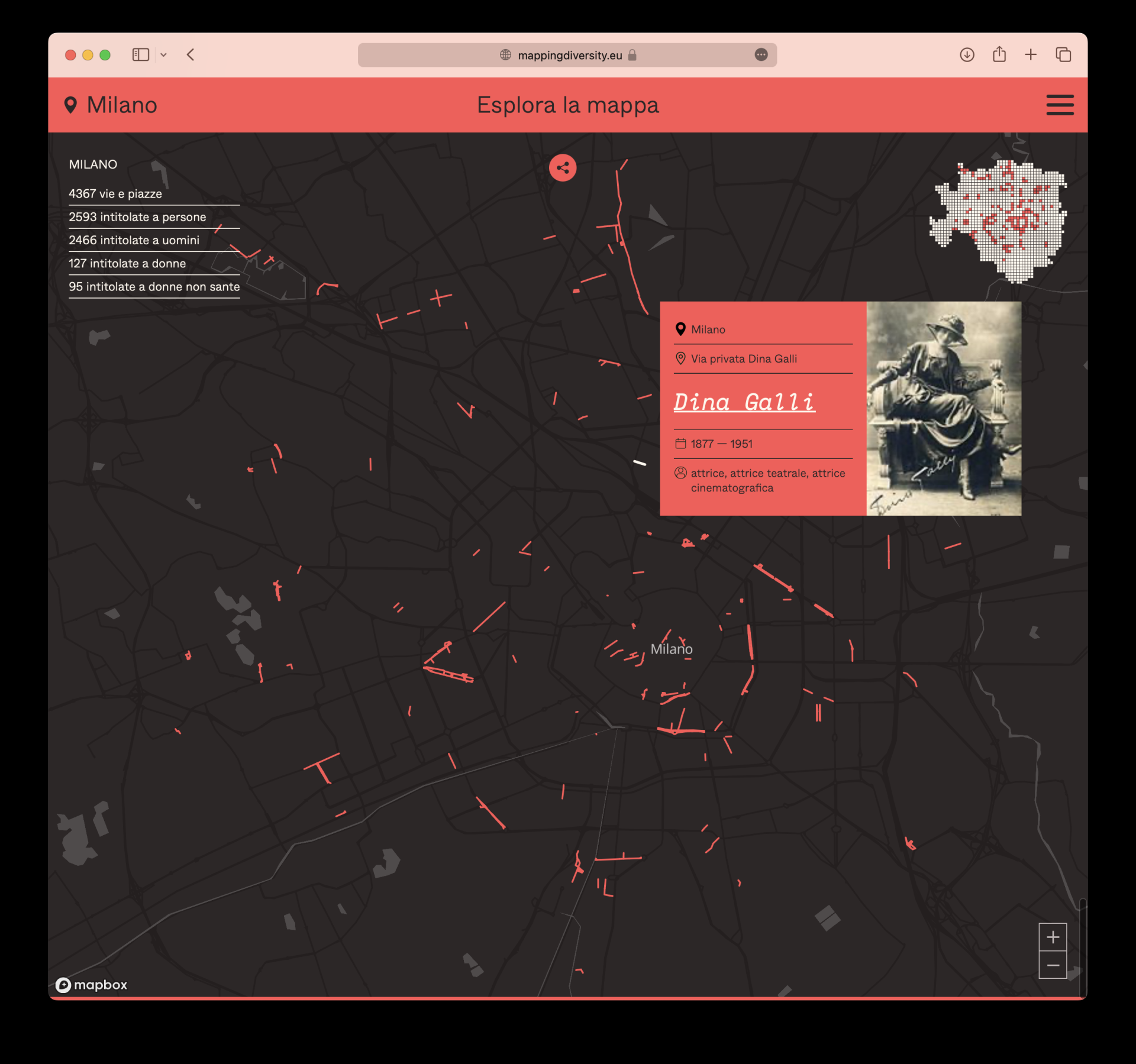

The Mapping Diversity platform sets out to answer this question. By combining linked open data with engaging visual storytelling, the reader can explore all the facts about the gender gap in major European cities. Visitors of the platform can read summary statistics about the street names across European cities and drill down in maps to discover specific street name dedications. With a click, a visitor can auto-generate a social media card with data visualisations and insight on the selected city and quickly share it to start a conversation about the gendered dynamics behind street names. In this way, the experience goes beyond that of an individual’s screen. It populates the (digital) public sphere with provocative facts about the stereotypes and power dynamics embedded in our urban lives.

The Mapping Diversity platform sets out to answer this question. By combining linked open data with engaging visual storytelling, the reader can explore all the facts about the gender gap in major European cities. Visitors of the platform can read summary statistics about the street names across European cities and drill down in maps to discover specific street name dedications. With a click, a visitor can auto-generate a social media card with data visualisations and insight on the selected city and quickly share it to start a conversation about the gendered dynamics behind street names. In this way, the experience goes beyond that of an individual’s screen. It populates the (digital) public sphere with provocative facts about the stereotypes and power dynamics embedded in our urban lives.

Key objectives for sustainability

The project addresses the issue of “social sustainability” because it functions as a platform that increases community participation within civil society and encourages a public debate that reinforces shared values and equal rights.

Mapping Diversity has been built as a “digital commons” to achieve this. Much like the traditional theorisation of “commons”, the term digital commons references a radical concept in which the ownership and care for the goods are shared between community members, whose role becomes that of active participants rather than consumers of - in this case - data, information, and knowledge.

The Mapping Diversity is an exemplar case of digital commons. Thus a project that contributes to social sustainability because of three main characteristics:

1. It enhances media and data literacy through active participation.

The platform is an entry point to a complex dataset that would otherwise be inaccessible to most people. Citizens are given access to the whole data transparently while at the same time being guided to make sense of this complexity through a scroll-based progressive reveal of data which makes it easier to parse and comprehend. This ultimately promotes media and data literacy skills.

2. It favours a participatory appropriation of the data.

Citizens are invited to actively submit updates and edits to the data in a way that removes all technical barriers. With a few clicks, they can also share the data insights that they find most relevant, nurturing a fact-based public debate.

3. It offers equitable access to information that is of paramount importance for shaping the public debate on civil rights issues.

Because of the previous two points, ultimately, Mapping Diversity contributes to an equitable public debate in which all citizens have at their disposal and under their care information that would otherwise be in the hands of few.

Mapping Diversity has been built as a “digital commons” to achieve this. Much like the traditional theorisation of “commons”, the term digital commons references a radical concept in which the ownership and care for the goods are shared between community members, whose role becomes that of active participants rather than consumers of - in this case - data, information, and knowledge.

The Mapping Diversity is an exemplar case of digital commons. Thus a project that contributes to social sustainability because of three main characteristics:

1. It enhances media and data literacy through active participation.

The platform is an entry point to a complex dataset that would otherwise be inaccessible to most people. Citizens are given access to the whole data transparently while at the same time being guided to make sense of this complexity through a scroll-based progressive reveal of data which makes it easier to parse and comprehend. This ultimately promotes media and data literacy skills.

2. It favours a participatory appropriation of the data.

Citizens are invited to actively submit updates and edits to the data in a way that removes all technical barriers. With a few clicks, they can also share the data insights that they find most relevant, nurturing a fact-based public debate.

3. It offers equitable access to information that is of paramount importance for shaping the public debate on civil rights issues.

Because of the previous two points, ultimately, Mapping Diversity contributes to an equitable public debate in which all citizens have at their disposal and under their care information that would otherwise be in the hands of few.

Key objectives for aesthetics and quality

In Mapping Diversity, design and UX play a central role as they are the key components through which it achieves the social sustainability goals detailed in the previous paragraphs. In this context, then, design and UX are not only a matter of embellishing or producing new frills, rather they are a means to make complex issues accessible and understandable to a wider audience, allowing information to break through the filter bubbles of audiences already familiar with the topics - like experts in design, data or gender issues.

In practice, this has been achieved thanks to clear low-density visualisations, each dealing with one facet of the data. Additionally, the visualisations are gradually revealed through a scroll-based animation, and each newly revealed fragment of the visualisation is accompanied by explanatory text. All these features enable less data-savvy population segments to understand complex data intuitively.

In practice, this has been achieved thanks to clear low-density visualisations, each dealing with one facet of the data. Additionally, the visualisations are gradually revealed through a scroll-based animation, and each newly revealed fragment of the visualisation is accompanied by explanatory text. All these features enable less data-savvy population segments to understand complex data intuitively.

Key objectives for inclusion

In Mapping Diversity, inclusion is a value we had in mind both when reasoning about its design and reflecting on its desired impact.

In terms of design, as detailed in the previous section, we have taken great care in devising visual and UX elements that favour equitable access to information by making complexity clear and engaging to experts and non-experts alike. This has been achieved, for example, through low-density visualisations and their scroll-based progressive reveal.

In terms of impact, we undertook this project with the goal of favouring a critical public debate about bias and diversity embedded in our everyday lives. Therefore, our metric of success in relation to this is closely linked to the number of media mentions and public references to our project. The Mapping Diversity pilot project launched in Italy in 2021 supported the publication of more than 50 articles in the national press and 32k visitors in a single year. With the newly published platform covering more than 70 European cities, we expect these numbers will scale accordingly and amplify the scope of the ongoing debate.

In terms of design, as detailed in the previous section, we have taken great care in devising visual and UX elements that favour equitable access to information by making complexity clear and engaging to experts and non-experts alike. This has been achieved, for example, through low-density visualisations and their scroll-based progressive reveal.

In terms of impact, we undertook this project with the goal of favouring a critical public debate about bias and diversity embedded in our everyday lives. Therefore, our metric of success in relation to this is closely linked to the number of media mentions and public references to our project. The Mapping Diversity pilot project launched in Italy in 2021 supported the publication of more than 50 articles in the national press and 32k visitors in a single year. With the newly published platform covering more than 70 European cities, we expect these numbers will scale accordingly and amplify the scope of the ongoing debate.

Results in relation to category

Mapping Diversity is, in its essence, a transdisciplinary endeavour. As reflected in the long list of the project’s credits, Mapping Diversity stems from the knowledge and work of all the activists, gender experts, designers, data analysts, and developers that actively contributed to its success. The combination of such a heterogeneous working group positively impacted the project’s outcome, although it required months of negotiations, mediation, and reflections that emerged during the several co-design sessions. Ultimately, this choral effort was crucial in establishing the added value of Mapping Diversity, allowing the project to reach beyond the bubbles of designers, activists, or data experts.

–––

Please give information on the results, outcomes and impacts achieved by your project in relation to the category you apply for. This includes also benefits from the project for direct and indirect beneficiaries *Maximum 2000 characters

Given the Mapping Diversity digital commons nature, the impact is two folded

Direct impact:

The pilot project Mapping Diversity, launched in Italy in 2021, resulted in more than 50 articles in the national press and 32,000 visitors in just one year. With the newly published platform covering more than 70 European cities, we expect these numbers to increase accordingly and amplify the scope of the ongoing debate.

Indirect impact:

Thanks to the attention generated by the media, the project has brought to the fore the debate on the inclusiveness of cities, starting with toponymy. An important debate, and one that in Italy had never been so strong and significant. Thanks to the data made available, the project served:

- Activists to promote their campaigns and initiatives

- Journalists to produce new articles on the state of their cities

- Mayors and administrators have one more tool to decide who to name new streets after.

–––

Please give information on the results, outcomes and impacts achieved by your project in relation to the category you apply for. This includes also benefits from the project for direct and indirect beneficiaries *Maximum 2000 characters

Given the Mapping Diversity digital commons nature, the impact is two folded

Direct impact:

The pilot project Mapping Diversity, launched in Italy in 2021, resulted in more than 50 articles in the national press and 32,000 visitors in just one year. With the newly published platform covering more than 70 European cities, we expect these numbers to increase accordingly and amplify the scope of the ongoing debate.

Indirect impact:

Thanks to the attention generated by the media, the project has brought to the fore the debate on the inclusiveness of cities, starting with toponymy. An important debate, and one that in Italy had never been so strong and significant. Thanks to the data made available, the project served:

- Activists to promote their campaigns and initiatives

- Journalists to produce new articles on the state of their cities

- Mayors and administrators have one more tool to decide who to name new streets after.

How Citizens benefit

The project involved several civil society actors right from its inception when we contacted local activists who had carried out smaller projects mapping gender diversity in street names. This allowed us to implement a co-design strategy focused on understanding what worked in these previous projects, what had been an obstacle to their scaling, and what had been important lessons learned in terms of data collection, verification, and classification. This has helped us avoid the “reinvent the wheel” outcome typical of many data projects by building a platform that stemmed from previous knowledge and harnessed technology to surpass hurdles that prevented the existing projects from having a wide impact.

Besides activists, Mapping Diversity has also considered common citizens when developing a strategy to scale its reach and impact. This has been achieved by providing tools, like the ability to quickly generate social media cards from data insights, that empower citizens’ active participation in a way that unites low effort requirements from the citizen with network effect for a large potential scale.

Besides activists, Mapping Diversity has also considered common citizens when developing a strategy to scale its reach and impact. This has been achieved by providing tools, like the ability to quickly generate social media cards from data insights, that empower citizens’ active participation in a way that unites low effort requirements from the citizen with network effect for a large potential scale.

Physical or other transformations

It refers to other types of transformations (soft investment)

Innovative character

There are not many mainstream actions in the field. In contrast, there are some pre-existing projects on which Mapping Diversity has drawn inspiration or worked in synergy with.

For example, Mapping Diversity consulted activists from the group behind “Toponomastica Femminile”, the first Italian project on gender toponymy. Through this discussion, we gained insights into the existing best practices to classify female street names, and we improved on them by automating the system so that it could scale easily.

Additionally, the project integrates open data from existing sources, Open Street Map (for data on street names) and Wikidata/Wikimedia (for data on gender and other biographic information on the streetnames). It is from the act of automatically combining these two otherwise independent, an open datasets that our project generates added value.

There are other digital projects combining these datasets, such as EqualStreetNames. These projects act as a repository of statistics about the cities that they cover, but they completely lack all the narrative aspects present in Mapping Diversity. This is a crucial difference, as it enables Mapping Diversity to make the information relevant and accessible to a wider audience to access content that used to belong to narrow insider circles beyond that of data experts.

For example, Mapping Diversity consulted activists from the group behind “Toponomastica Femminile”, the first Italian project on gender toponymy. Through this discussion, we gained insights into the existing best practices to classify female street names, and we improved on them by automating the system so that it could scale easily.

Additionally, the project integrates open data from existing sources, Open Street Map (for data on street names) and Wikidata/Wikimedia (for data on gender and other biographic information on the streetnames). It is from the act of automatically combining these two otherwise independent, an open datasets that our project generates added value.

There are other digital projects combining these datasets, such as EqualStreetNames. These projects act as a repository of statistics about the cities that they cover, but they completely lack all the narrative aspects present in Mapping Diversity. This is a crucial difference, as it enables Mapping Diversity to make the information relevant and accessible to a wider audience to access content that used to belong to narrow insider circles beyond that of data experts.

Disciplines/knowledge reflected

Mapping Diversity is, in its essence, a transdisciplinary endeavour. As reflected in the long list of the project’s credits, Mapping Diversity stems from the knowledge and work of all the activists, gender experts, designers, data analysts, and developers that actively contributed to its success. The combination of such a heterogeneous working group positively impacted the project’s outcome, although it required months of negotiations, mediation, and reflections that emerged during the several co-design sessions. Ultimately, this choral effort was crucial in establishing the added value of Mapping Diversity, allowing the project to reach beyond the bubbles of designers, activists, or data experts.

Methodology used

From the design point of view, the primary methodology was that of collaborative design, described above, which made it possible to bring together and give voice to a diverse range of people and professions. The collaborative design came to life thanks to a series of workshops involving both the professionals directly involved and domain experts, such as activists connected to the world of data and gender issues. Thanks to the workshops, it was possible to give voice to all possible demands, from data access to those related to inclusive language.

From the point of view of the content, the platform heavily relies on a unique and innovative data collection process. The data analyst and the developers in the team produced a novel system to automatically leverage Linked Open Data (LOD). The developed software imports Open Street Map data about the selected cities and automatically searches for them in Wikidata/Wikipedia through unique identifiers (URI). The system flags any street names that may need manual verification, for example, to disambiguate between homonyms or to fill in information about people that are not on Wikidata

The data verification team has access to a custom interface to further process the data that needs manual verification. The interface makes it easy to disambiguate entries and add missing information directly in Wikipedia.

This system makes the entire project replicable and scalable. At the same time, it furtherly fulfils its “digital commons nature”: on the one hand, it draws on open and crowd-sourced data, which has been created through the active participation of communities. On the other hand, it uses technology (the data verification custom interface) to give back to this community by enriching Wikipedia with new information or correcting data on Open Street Map, if needed.

From the point of view of the content, the platform heavily relies on a unique and innovative data collection process. The data analyst and the developers in the team produced a novel system to automatically leverage Linked Open Data (LOD). The developed software imports Open Street Map data about the selected cities and automatically searches for them in Wikidata/Wikipedia through unique identifiers (URI). The system flags any street names that may need manual verification, for example, to disambiguate between homonyms or to fill in information about people that are not on Wikidata

The data verification team has access to a custom interface to further process the data that needs manual verification. The interface makes it easy to disambiguate entries and add missing information directly in Wikipedia.

This system makes the entire project replicable and scalable. At the same time, it furtherly fulfils its “digital commons nature”: on the one hand, it draws on open and crowd-sourced data, which has been created through the active participation of communities. On the other hand, it uses technology (the data verification custom interface) to give back to this community by enriching Wikipedia with new information or correcting data on Open Street Map, if needed.

How stakeholders are engaged

OBCT, partner and initiator of the project, made its European network of Data Journalists available both to collect and verify data, as well as to contribute to the writing of language articles helpful to amplify the project's impact. More than 60 cities were involved.

Sheldon.studio is a newborn digital studio focusing on Data Design for social issues. Through several collaborative design workshops, the conversation on the project’s design, features, and objectives developed until the shaping of the current project.

Activists, experts on gender issues, and citizens participated in the collaborative workshops and user testing to develop an easy-to-understand approach to such a complex topic. User testing was informally led, asking participants about their understanding and experience after interacting with the project.

Sheldon.studio is a newborn digital studio focusing on Data Design for social issues. Through several collaborative design workshops, the conversation on the project’s design, features, and objectives developed until the shaping of the current project.

Activists, experts on gender issues, and citizens participated in the collaborative workshops and user testing to develop an easy-to-understand approach to such a complex topic. User testing was informally led, asking participants about their understanding and experience after interacting with the project.

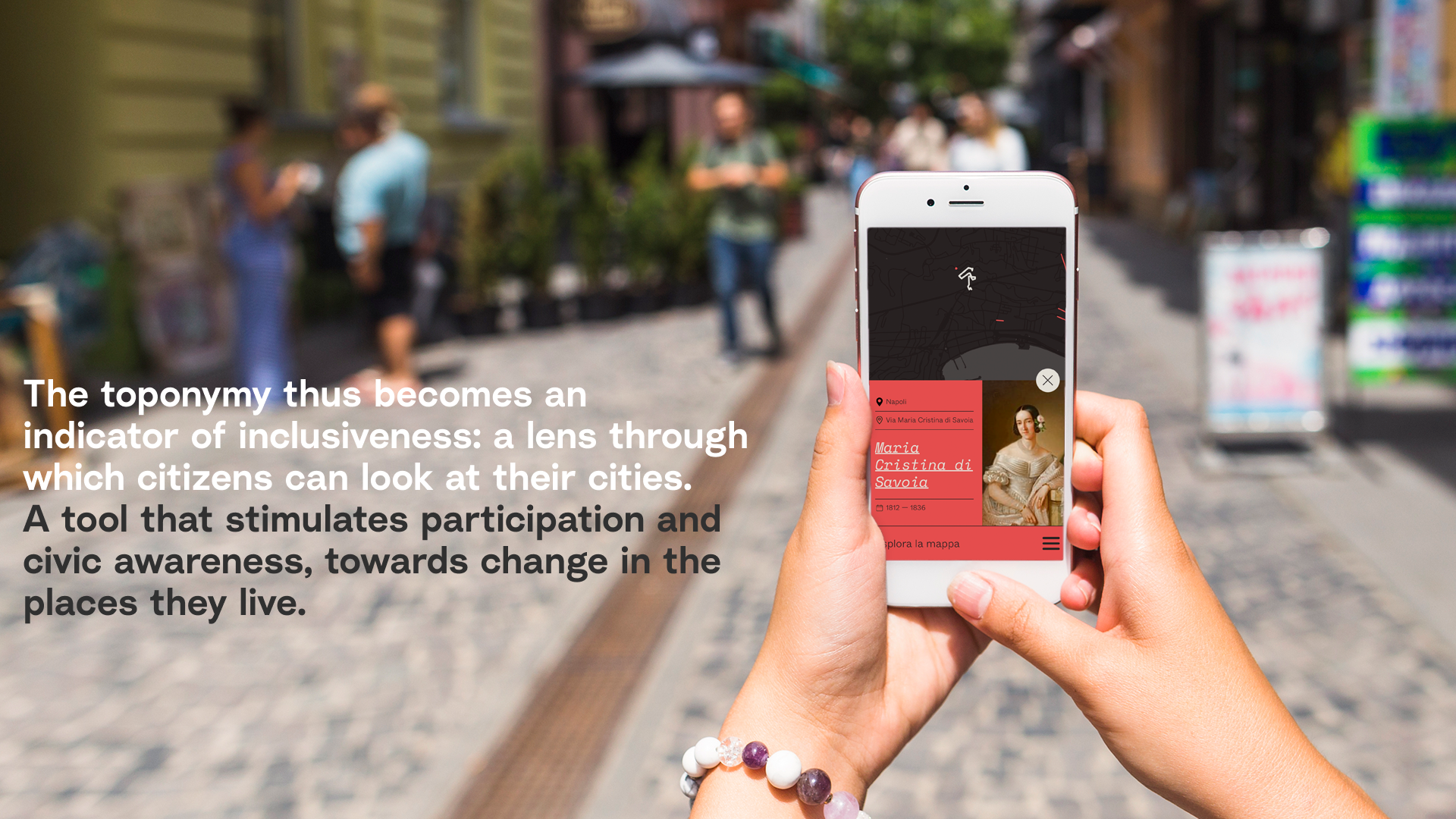

Global challenges

The project is part of the global challenge to make cities more inclusive places. The gender gap in toponymy says something about the kind of society we live in…and the one we perpetuate. The street names, it reflects the commemorative decisions of the municipalities and, as has also been done in various academic articles, they can be used as a proxy for their social and cultural characteristics (past or present). There is a link between toponymy, society and shared cultural values. According to a Spanish study (https://osf.io/b9n4k/), municipalities with a higher percentage of streets named after female figures also tend to boast more egalitarian numbers regarding female empowerment. We are in favour of a participatory and bottom-up approach towards more inclusive cities and inclusive street names. A top-down decision in which the mayor and local politicians, perhaps all men and all white, do a promotional photo shoot while replacing the license plate of a street and a limited stunt. On the other hand, there can be communities, activists and associations that instead initiate a radical reflection on the theme. Perhaps holding workshops, conferences and educational activities on the lack of diversity in the urban space, on the names that lack an urban commemoration and on what to do about it can instead have a more. Actions like these can have a significant impact, regardless of whether a street’s name change immediately follows them. And the Mapping Diversity platform has been designed precisely to support this type of participatory action: a tool that makes the necessary data accessible for this public and participatory debate to take place. The project, therefore, acts as a monitoring and support tool for a transformation of cities, which starts from the bottom, stimulating a feeling of belonging.

Learning transferred to other parties

Thanks to the methodology described above, the project is easily replicable in other places and countries. And that is exactly what happened. After the success of the Italian pilot, the working group decided to scale up the project to the European level. It was thus possible to collect data and publish the stories of dozens of European municipalities.

Similarly, the promotion methodology was also scaled up to the European level. Dozens of local newspapers acted as relays and multipliers of the project's impact, telling their citizens in their language about the situation in the cities where they live.

Finally, a last part on which we are working is the promotion of bottom-up initiatives involving activists and citizens in the participatory mapping of places that are currently not on the platform. These are either map-a-thons (collaborative mapping sessions) involving citizenship or training sessions in schools, educating students on the importance and value of data and the use of civic monitoring technologies.

Similarly, the promotion methodology was also scaled up to the European level. Dozens of local newspapers acted as relays and multipliers of the project's impact, telling their citizens in their language about the situation in the cities where they live.

Finally, a last part on which we are working is the promotion of bottom-up initiatives involving activists and citizens in the participatory mapping of places that are currently not on the platform. These are either map-a-thons (collaborative mapping sessions) involving citizenship or training sessions in schools, educating students on the importance and value of data and the use of civic monitoring technologies.

Keywords

Toponomy

Diversity

Europe

City

Gender