CO-HAB RAVAL

Basic information

Project Title

CO-HAB RAVAL

Full project title

Co-design and co-fabrication of rehabilitation solutions to improve the quality of life in El Raval

Category

Prioritising the places and people that need it the most

Project Description

This project articulates a methodology of assisted rehabilitation in vulnerable residential communities through the co-design of replicable, small-scale projects and their further co-fabrication and implementation in five multi-family buildings in the Raval neighbourhood. Efficient low-cost, recyclable, license-free solutions that can be self-constructed with the assistance of local professionals and entities respond to the local and global urgency of improving living spaces in deprived areas.

Geographical Scope

Local

Project Region

Barcelona, Spain

Urban or rural issues

Mainly urban

Physical or other transformations

It refers to other types of transformations (soft investment)

EU Programme or fund

No

Description of the project

Summary

This project addresses the urgency of improving living conditions in multi-family housing communities in deprived neighbourhoods through a bottom-up method of guided self-rehabilitation.

Barcelona’s Raval neighbourhood combines a high population density of inhabitants at risk of poverty and residential exclusion with a degraded building stock that fails to fulfil habitability requirements and is in need of expensive rehabilitation and heritage preservation.

This project consisted of the participatory design of a catalogue of small-scale solutions aimed at improving habitability in keeping with six principles: (1) sustainability, (2) interior air quality and sanitation, (3) inclusion, (4) care and health, (5) safety and (6) resilience. Low cost, perfectible, recyclable solutions designed in collaboration with residents meet urgent needs while respecting heritage protection. Several of these solutions were implemented in five multi-family buildings in the Raval. In each, we tested the feasibility of a guided self-rehabilitation process where residents worked on architectural solutions with help from local professionals.

The impact of the project is based on two characteristics: its bottom-up nature and its scalability. First, it relies on the capacity of residents and local entities to reconquer their right to housing and proactively transform their living spaces. Second, it is scalable thanks to the design of ‘plug-in’ solutions that were implemented in pilot cases and can be replicated in the rest of the neighbourhood or in similar contexts. We found that small-scale, participative socio-architectonic transformations can have a big impact by exploring the limits of simple and efficient constructive solutions that are low-cost, permit-free and do not require complex property agreements. Such projects can be easily managed and built by the residents themselves with help from local professionals.

Barcelona’s Raval neighbourhood combines a high population density of inhabitants at risk of poverty and residential exclusion with a degraded building stock that fails to fulfil habitability requirements and is in need of expensive rehabilitation and heritage preservation.

This project consisted of the participatory design of a catalogue of small-scale solutions aimed at improving habitability in keeping with six principles: (1) sustainability, (2) interior air quality and sanitation, (3) inclusion, (4) care and health, (5) safety and (6) resilience. Low cost, perfectible, recyclable solutions designed in collaboration with residents meet urgent needs while respecting heritage protection. Several of these solutions were implemented in five multi-family buildings in the Raval. In each, we tested the feasibility of a guided self-rehabilitation process where residents worked on architectural solutions with help from local professionals.

The impact of the project is based on two characteristics: its bottom-up nature and its scalability. First, it relies on the capacity of residents and local entities to reconquer their right to housing and proactively transform their living spaces. Second, it is scalable thanks to the design of ‘plug-in’ solutions that were implemented in pilot cases and can be replicated in the rest of the neighbourhood or in similar contexts. We found that small-scale, participative socio-architectonic transformations can have a big impact by exploring the limits of simple and efficient constructive solutions that are low-cost, permit-free and do not require complex property agreements. Such projects can be easily managed and built by the residents themselves with help from local professionals.

Key objectives for sustainability

The rehabilitation and adaptation of the existing housing stock to meet residents’ needs and offer comfortable, safe living spaces plays a central role in the achievement of the Green European Deal. Specifically, it contributes to Sustainability Development Goal 11: making cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable.

These aims have been addressed with the co-design of standardised solutions that are:

1.Easy to build. They can be implemented with guided self-construction involving residents and local professionals.

2.Perfectible. They are based on dry construction systems and are easily detachable from the built support so they do not compromise heritage protection and do not require complex building permits or property agreements.

3.Adaptable. They can be replicated and have an impact far beyond the pilot projects. They would work in most buildings in the Raval and in similar contexts (Mediterranean historic centres, vulnerable multi-family historic residential buildings).

4.Recyclable. Use of dry attached components through standardised solutions ensures circularity, attached solutions—or at least their components and materials—can be recycled, and no waste is generated if they are dismantled.

5.Participative. Involvement of residents helps to train them in the management, maintenance and re-use of built solutions, and it fosters the transformation of their habits into more environmentally and socially responsible practices.

The search for standardisation, replicability, circularity and perfectibility in rehabilitation is a mandatory path towards the sustainable adaptation and improvement of existing living spaces. Furthermore, the incorporation of community-led design in rehabilitation and the formal architectural approach to self-construction practices that are common and involve large populations in many contexts are key to advancing towards a more sustainable involvement of residents as proactive rehabilitation agents.

These aims have been addressed with the co-design of standardised solutions that are:

1.Easy to build. They can be implemented with guided self-construction involving residents and local professionals.

2.Perfectible. They are based on dry construction systems and are easily detachable from the built support so they do not compromise heritage protection and do not require complex building permits or property agreements.

3.Adaptable. They can be replicated and have an impact far beyond the pilot projects. They would work in most buildings in the Raval and in similar contexts (Mediterranean historic centres, vulnerable multi-family historic residential buildings).

4.Recyclable. Use of dry attached components through standardised solutions ensures circularity, attached solutions—or at least their components and materials—can be recycled, and no waste is generated if they are dismantled.

5.Participative. Involvement of residents helps to train them in the management, maintenance and re-use of built solutions, and it fosters the transformation of their habits into more environmentally and socially responsible practices.

The search for standardisation, replicability, circularity and perfectibility in rehabilitation is a mandatory path towards the sustainable adaptation and improvement of existing living spaces. Furthermore, the incorporation of community-led design in rehabilitation and the formal architectural approach to self-construction practices that are common and involve large populations in many contexts are key to advancing towards a more sustainable involvement of residents as proactive rehabilitation agents.

Key objectives for aesthetics and quality

The projects’ key aesthetic goals are based on the socio-architectural and multi-scalar nature of the proposals.

First, participation by residents in the co-design of solutions and implementation processes calls for an open system that can embed multiple aesthetic configurations to meet the desires of different residents and communities. Solutions must deal with historic heritage elements and spaces with deformations and degradations caused by the passage of time and intensive use; as a result, open systems must be able to adapt to fit irregular shapes, and prefabrication is nearly impossible.

Although design solutions take shape on a small scale, the goal is for them to be applied to the transformation of the shared spaces of entire residential communities. These solutions can be applied to most—if not all—buildings in the Raval. As a result, a shared aesthetic can lead to transformations on an urban scale.

The proposed aesthetics simultaneously meet requirements on diversity, adaptability, scalability and universality. Each project was seen as part of a larger whole involving universal, open designs based on standardized constructive systems and local—often recycled—materials. Implemented solutions are replicable and recyclable and their shared aesthetics provide common ground for participative and adaptable formal configurations. This system is based on:

1. Industrialized components of adjustable size based on dry construction systems that can be adapted to fit different physical supports (irregular roof slopes and shapes, different types of stairs, irregular windows, etc.).

2. Open structures that can incorporate variable plug-in components (plants, shades, storage compartments, furniture, services, etc.)

3. Open designs that rely on the conceptual, methodological and tangible universality of open support structures to provide a design base that can admit variable and adaptable finishings (colours, materials, textures, etc.).

First, participation by residents in the co-design of solutions and implementation processes calls for an open system that can embed multiple aesthetic configurations to meet the desires of different residents and communities. Solutions must deal with historic heritage elements and spaces with deformations and degradations caused by the passage of time and intensive use; as a result, open systems must be able to adapt to fit irregular shapes, and prefabrication is nearly impossible.

Although design solutions take shape on a small scale, the goal is for them to be applied to the transformation of the shared spaces of entire residential communities. These solutions can be applied to most—if not all—buildings in the Raval. As a result, a shared aesthetic can lead to transformations on an urban scale.

The proposed aesthetics simultaneously meet requirements on diversity, adaptability, scalability and universality. Each project was seen as part of a larger whole involving universal, open designs based on standardized constructive systems and local—often recycled—materials. Implemented solutions are replicable and recyclable and their shared aesthetics provide common ground for participative and adaptable formal configurations. This system is based on:

1. Industrialized components of adjustable size based on dry construction systems that can be adapted to fit different physical supports (irregular roof slopes and shapes, different types of stairs, irregular windows, etc.).

2. Open structures that can incorporate variable plug-in components (plants, shades, storage compartments, furniture, services, etc.)

3. Open designs that rely on the conceptual, methodological and tangible universality of open support structures to provide a design base that can admit variable and adaptable finishings (colours, materials, textures, etc.).

Key objectives for inclusion

This project applies the “design for all” concept in terms of both target and proposed actions.

First, it addresses vulnerable households—communities living in multi-family housing in deprived urban areas who can barely improve their living conditions due to complex economic, social and technical impediments. Public rehabilitation programs have difficulty targeting the communities and residents who need them the most. It is even more difficult for them to do so in a quantitative way that can simultaneously benefit many communities in the short and medium term. This project contributes to research on low-cost, efficient solutions that can be self-managed and self-built proactively by residents with the support of the local productive and associative fabric. It is based on confidence in and appreciation of local capacities.

Another of the project’s guiding design axes is inclusion; it seeks to improve accessibility and habitability for a diverse range of residents in all stages of life with variable needs and aspirations. Common residential spaces are key to inclusion, as they provide intermediate spaces between private homes and public areas. Often, the lack of private spaces for certain domestic activities can be compensated with flexible, more resilient spaces for care and health, comfort, diversity and cohabitation. For example, exterior common spaces for residents to meet spontaneously and practice co-appropriation or more comfortable, safer circulation spaces that foster continuity and communication instead of acting as barriers.

Finally, inclusion was ensured by embracing citizens and residents’ participation in all phases of the project. Co-design and co-fabrication processes provided an environment and pretext for citizen empowerment and organization and turned into powerful experiences of community mutual support and proactive learning.

First, it addresses vulnerable households—communities living in multi-family housing in deprived urban areas who can barely improve their living conditions due to complex economic, social and technical impediments. Public rehabilitation programs have difficulty targeting the communities and residents who need them the most. It is even more difficult for them to do so in a quantitative way that can simultaneously benefit many communities in the short and medium term. This project contributes to research on low-cost, efficient solutions that can be self-managed and self-built proactively by residents with the support of the local productive and associative fabric. It is based on confidence in and appreciation of local capacities.

Another of the project’s guiding design axes is inclusion; it seeks to improve accessibility and habitability for a diverse range of residents in all stages of life with variable needs and aspirations. Common residential spaces are key to inclusion, as they provide intermediate spaces between private homes and public areas. Often, the lack of private spaces for certain domestic activities can be compensated with flexible, more resilient spaces for care and health, comfort, diversity and cohabitation. For example, exterior common spaces for residents to meet spontaneously and practice co-appropriation or more comfortable, safer circulation spaces that foster continuity and communication instead of acting as barriers.

Finally, inclusion was ensured by embracing citizens and residents’ participation in all phases of the project. Co-design and co-fabrication processes provided an environment and pretext for citizen empowerment and organization and turned into powerful experiences of community mutual support and proactive learning.

Results in relation to category

The project's most significant outcome was the development of an open-source system that empowered vulnerable communities to access and repurpose underutilized spaces at low cost. This initiative successfully transformed neglected areas into functional, inclusive environments for those in greatest need. By providing a structured framework, the project enabled marginalized groups to take control of their living spaces, fostering a sense of ownership and belonging. As a result, the community experienced a tangible improvement in living conditions, marking a significant step towards greater social equity and inclusivity. This innovative approach not only addressed a pressing urban issue but also served as a model for similar initiatives in other communities.

Through inclusive workshops, participatory design processes, and open forums, it ensured that the community's voice was not only heard but also directly incorporated into decision-making. This collaborative approach not only fostered a sense of ownership among residents but also created a collective vision for the project's success. Moreover, the project showcased a strong commitment to Sustainability and Innovation by implementing eco-friendly construction methods and utilizing locally-sourced, recycled materials.

Additionally, its innovative use of technology streamlined processes, making them more cost-effective and replicable. Social Integration and Engagement were paramount, as the project focused on breaking down barriers and forging connections among diverse community members. Through targeted programs and events, it encouraged dialogue, cultural exchange, and mutual support, ultimately fostering a more inclusive and cohesive neighborhood fabric. This multifaceted approach not only improved physical spaces but also created a vibrant, socially integrated community that thrived on collaboration and shared experiences.

Through inclusive workshops, participatory design processes, and open forums, it ensured that the community's voice was not only heard but also directly incorporated into decision-making. This collaborative approach not only fostered a sense of ownership among residents but also created a collective vision for the project's success. Moreover, the project showcased a strong commitment to Sustainability and Innovation by implementing eco-friendly construction methods and utilizing locally-sourced, recycled materials.

Additionally, its innovative use of technology streamlined processes, making them more cost-effective and replicable. Social Integration and Engagement were paramount, as the project focused on breaking down barriers and forging connections among diverse community members. Through targeted programs and events, it encouraged dialogue, cultural exchange, and mutual support, ultimately fostering a more inclusive and cohesive neighborhood fabric. This multifaceted approach not only improved physical spaces but also created a vibrant, socially integrated community that thrived on collaboration and shared experiences.

How Citizens benefit

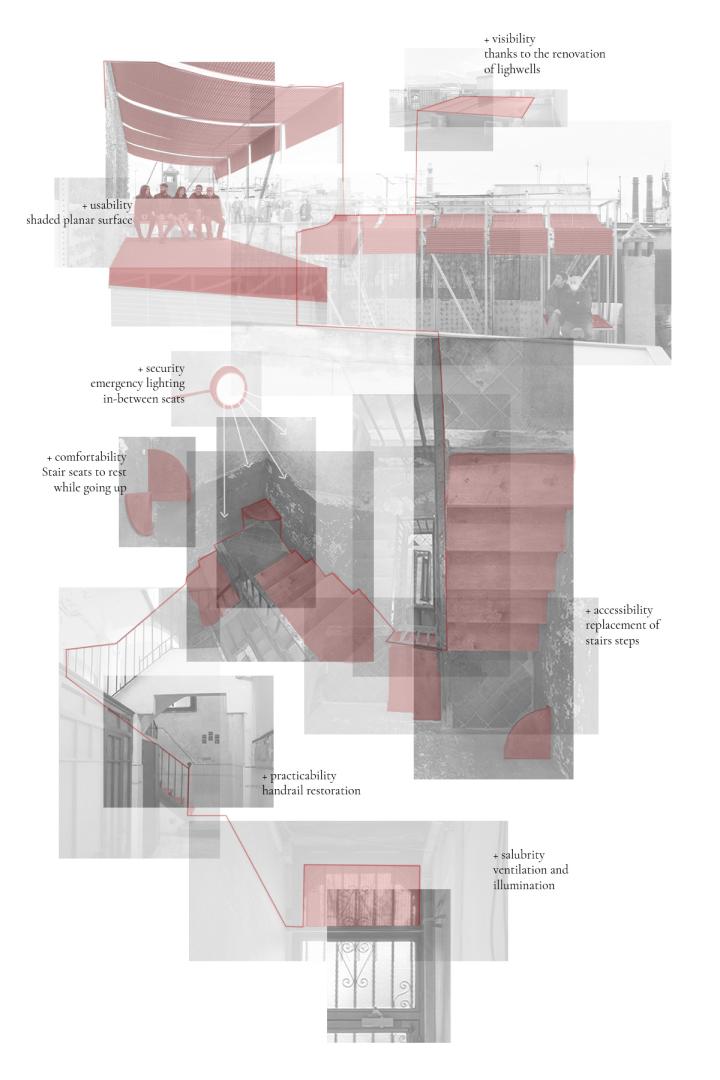

The safety and accessibility of staircases are improved with interventions in steps and railings. The lighting is also improved; energy consumption is reduced using more efficient LED technology, and residents’ perception of comfort and their experience of colour and light are improved. Air quality is improved with greater ventilation through selective openings throughout the building; this also brings in more natural light and provides greater views. This is done in keeping with residents’ desire to dignify entryways and staircases without compromising their privacy. Finally, pollutants and obsolete installations are removed from rooves, and new structures are added to provide a flat surface, additional storage, more shade, greenery and new furniture; this addresses all six conceptual axes.

This project addresses the needs of vulnerable areas, communities and individuals requiring specific, urgent attention. As a result, its results and impacts are both methodological and applicable.

Regarding the materialization of solutions, two pilot communities prioritised an intervention adding a pergola to the shared rooftop space to promote well-being and cohabitation. Two different versions of the same adaptable dry construction structure were built with recycled, local materials; they included greenery, shade and storage space. Two other communities chose to improve ventilation and illumination through the selective replacement of existing openings and light systems throughout the entryway and staircase. Finally, one community agreed on an intervention to make the stairs more accessible, beautiful and safe. With costs ranging from 5,000 to €15,500, built solutions required little or no maintenance and simultaneously improved sustainability, inclusion and aesthetics. They are directly replicable in most vulnerable multi-family housing communities in the Raval (up to 17,300 dwellings and 48,688 inhabitants) or in similar contexts.

This project addresses the needs of vulnerable areas, communities and individuals requiring specific, urgent attention. As a result, its results and impacts are both methodological and applicable.

Regarding the materialization of solutions, two pilot communities prioritised an intervention adding a pergola to the shared rooftop space to promote well-being and cohabitation. Two different versions of the same adaptable dry construction structure were built with recycled, local materials; they included greenery, shade and storage space. Two other communities chose to improve ventilation and illumination through the selective replacement of existing openings and light systems throughout the entryway and staircase. Finally, one community agreed on an intervention to make the stairs more accessible, beautiful and safe. With costs ranging from 5,000 to €15,500, built solutions required little or no maintenance and simultaneously improved sustainability, inclusion and aesthetics. They are directly replicable in most vulnerable multi-family housing communities in the Raval (up to 17,300 dwellings and 48,688 inhabitants) or in similar contexts.

Physical or other transformations

It refers to other types of transformations (soft investment)

Innovative character

The rehabilitation of shared spaces in multi-family housing is a common practice that requires community agreements, a technical project and a building permit. In the Raval, these actions usually involve investments ranging from €50,000 to €150,000 depending on the building and the complexity of the required intervention. Although there is a widespread need for large-scale rehabilitation, the communities that need it most face strong impediments to carrying out self-financed and self-managed interventions. This proposal provides an exploration of the limits and potential of alternative, affordable, small-scale solutions (€5,000-€15,000/building) with an impact throughout the building thanks to the combination of many small interventions in common spaces.

This project uses a bottom-up, collaborative methodology that not only includes citizen participation in decision-making but is also based on local capacities for the materialisation and replication of solutions. There are increasingly common experiences of assisted self-rehabilitation, but most consist of repairing specific or partial damages. Here, rehabilitation is seen as a multi-scalar and multi-faceted opportunity to transform and improve living spaces not only to meet technical requirements but also to offer more sustainable, inclusive, beautiful spaces that enhance new living experiences and cohabitation practices.

While there are great examples of improving shared spaces in cooperative communities and public social housing, common spaces in existing privately-owned multi-family buildings are neglected in the academic world of architecture and design. Furthermore, low-cost, perfectible and standardised solutions are often limited to temporary or furniture-like elements in domestic or public urban spaces. Research on the design and implementation of small-scale affordable systems that can permanently attach to existing spaces (at least in the medium term) and improve their performance is less common.

This project uses a bottom-up, collaborative methodology that not only includes citizen participation in decision-making but is also based on local capacities for the materialisation and replication of solutions. There are increasingly common experiences of assisted self-rehabilitation, but most consist of repairing specific or partial damages. Here, rehabilitation is seen as a multi-scalar and multi-faceted opportunity to transform and improve living spaces not only to meet technical requirements but also to offer more sustainable, inclusive, beautiful spaces that enhance new living experiences and cohabitation practices.

While there are great examples of improving shared spaces in cooperative communities and public social housing, common spaces in existing privately-owned multi-family buildings are neglected in the academic world of architecture and design. Furthermore, low-cost, perfectible and standardised solutions are often limited to temporary or furniture-like elements in domestic or public urban spaces. Research on the design and implementation of small-scale affordable systems that can permanently attach to existing spaces (at least in the medium term) and improve their performance is less common.

Disciplines/knowledge reflected

Thanks to the collaborative methodology used, alliances were created between different sectors: organised and non-organized residents, owners and renters, associations, local professionals, academic researchers, and students. 17 local businesses with more than 30 professionals took part in the co-design and co-fabrication processes. Four local non-profit entities informed and assessed the project, with one being part of the team. Gender equality was achieved throughout the process and in different participation teams, with more than 55% of women overall.

Architectural Research experts brought architectural knowledge, experience, and research skills to the project. They focused on the typification, characterization, and diagnosis of various buildings. Their contribution helped establish the socio-demographic profile and living conditions of the residents. Their expertise was essential in understanding the physical structures and environments.

Sociologists were involved in understanding the social dynamics, needs, and impacts of the project. They conducted research on urban sociology and public policy evaluation. Their input helped in identifying and addressing social aspects related to the project.

Community Engagement members brought valuable community insights and advocacy skills. They collaborated with local residents and organisations, ensuring that the project aligned with the needs and aspirations of the community.

The added value of this interdisciplinary collaboration was a holistic approach to the project. It ensured that not only the physical structures but also the social and legal aspects were considered. This enriched the project's outcomes, making them more relevant and applicable to the target community. The diverse perspectives led to comprehensive solutions that addressed both the tangible and intangible needs of the residents.

Architectural Research experts brought architectural knowledge, experience, and research skills to the project. They focused on the typification, characterization, and diagnosis of various buildings. Their contribution helped establish the socio-demographic profile and living conditions of the residents. Their expertise was essential in understanding the physical structures and environments.

Sociologists were involved in understanding the social dynamics, needs, and impacts of the project. They conducted research on urban sociology and public policy evaluation. Their input helped in identifying and addressing social aspects related to the project.

Community Engagement members brought valuable community insights and advocacy skills. They collaborated with local residents and organisations, ensuring that the project aligned with the needs and aspirations of the community.

The added value of this interdisciplinary collaboration was a holistic approach to the project. It ensured that not only the physical structures but also the social and legal aspects were considered. This enriched the project's outcomes, making them more relevant and applicable to the target community. The diverse perspectives led to comprehensive solutions that addressed both the tangible and intangible needs of the residents.

Methodology used

The project employed a multi-disciplinary and participatory methodology to address the complex challenges of urban revitalization. Eleven communities were studied in detail, and five communities consisting of 61 dwellings and a population of 95 residents were chosen for pilot projects. 30 residents were involved in the co-design and co-fabrication of solutions in their shared spaces.

Following this, a participatory approach was adopted, involving local residents, experts, and stakeholders in co-design workshops and discussions. This collaborative process ensured that the community's needs, preferences, and cultural nuances were central to the project's development. It allowed for a diverse range of perspectives to shape the design and implementation phases.

In parallel, the project prioritised sustainability and innovation by integrating eco-friendly construction techniques and utilising recyclable, locally-sourced and easy to access materials. This approach not only reduced environmental impact but also served as a model for sustainable urban interventions.

Throughout the project, continuous feedback loops were established to refine designs and strategies. Prototypes were developed and tested, with real-world applicability and adaptability in mind. This iterative process ensured that the final solutions were not only technically sound but also culturally and socially relevant.

Furthermore, the project placed a strong emphasis on capacity-building and community empowerment. Workshops, training sessions, and skill-building initiatives were organised to enhance the capabilities of local residents, enabling them to actively participate in the project and take ownership of the rooftop spaces.

Following this, a participatory approach was adopted, involving local residents, experts, and stakeholders in co-design workshops and discussions. This collaborative process ensured that the community's needs, preferences, and cultural nuances were central to the project's development. It allowed for a diverse range of perspectives to shape the design and implementation phases.

In parallel, the project prioritised sustainability and innovation by integrating eco-friendly construction techniques and utilising recyclable, locally-sourced and easy to access materials. This approach not only reduced environmental impact but also served as a model for sustainable urban interventions.

Throughout the project, continuous feedback loops were established to refine designs and strategies. Prototypes were developed and tested, with real-world applicability and adaptability in mind. This iterative process ensured that the final solutions were not only technically sound but also culturally and socially relevant.

Furthermore, the project placed a strong emphasis on capacity-building and community empowerment. Workshops, training sessions, and skill-building initiatives were organised to enhance the capabilities of local residents, enabling them to actively participate in the project and take ownership of the rooftop spaces.

How stakeholders are engaged

The project is a pioneering experience in capacity-building and cooperation between academics, non-profit local entities, the local productive fabric and civil society, with the financial support of the public administration. It was carried out by a team of architectural researchers, including members of a local non-profit who work hand in hand with the local population on a daily basis.

Citizen participation was included in all phases and consisted of:

1. A focus group of three local non-profits (a neighbourhood association, an entity that supports vulnerable populations and an organization of local professionals) accompanied the development of the project, offering a global view on both local needs and potentials for the implementation and replicability of solutions.

2. A first round of participatory processes where the needs and aspirations of residential communities were collected informed a draft catalogue of micro-projects. These were further co-designed, criticized, transformed and assessed in a second round of participation.

3. Residents of five pilot communities, together with local professionals, were involved in a deeper phase of co-design and prioritization of solutions to be implemented in their common spaces.

4. In the co-construction phase, residents who had building experience and skills helped to execute parts of the transformation with the assistance of local professionals, while others helped to organize, clean, cook and, in general, apply self-organization, mutual support and community-sharing.

Regarding sustainability, residents learned how to use and maintain their common spaces in more environmentally and socially responsible ways. Regarding inclusion, residents’ diverse needs and aspirations were negotiated and consensual agreements were reached; this resulted in more diverse aesthetic configurations. Residents’ satisfaction with their everyday living spaces and communities improved significantly.

Citizen participation was included in all phases and consisted of:

1. A focus group of three local non-profits (a neighbourhood association, an entity that supports vulnerable populations and an organization of local professionals) accompanied the development of the project, offering a global view on both local needs and potentials for the implementation and replicability of solutions.

2. A first round of participatory processes where the needs and aspirations of residential communities were collected informed a draft catalogue of micro-projects. These were further co-designed, criticized, transformed and assessed in a second round of participation.

3. Residents of five pilot communities, together with local professionals, were involved in a deeper phase of co-design and prioritization of solutions to be implemented in their common spaces.

4. In the co-construction phase, residents who had building experience and skills helped to execute parts of the transformation with the assistance of local professionals, while others helped to organize, clean, cook and, in general, apply self-organization, mutual support and community-sharing.

Regarding sustainability, residents learned how to use and maintain their common spaces in more environmentally and socially responsible ways. Regarding inclusion, residents’ diverse needs and aspirations were negotiated and consensual agreements were reached; this resulted in more diverse aesthetic configurations. Residents’ satisfaction with their everyday living spaces and communities improved significantly.

Global challenges

The need to improve sustainability and living conditions in deprived areas of cities is a widespread global need, emphasized by an increasingly severe housing emergency in both the Global South and the Global North. In this context, the existing ageing housing stock provides more than 90% of available living spaces and contributes greatly to energy consumption. The urgent need to develop efficient, sustainable, affordable and far-reaching rehabilitation techniques and actions is more than justified globally.

In parallel, the field of architecture is experiencing a turn towards more collaborative and socially responsible practices that enhance citizen participation and empowerment and foster cohabitation and mutual support. The urgent need to improve quality of life in multi-family-housing in vulnerable urban communities can only be effectively approached through this transversal and collaborative approach to design.

Barcelona’s Raval neighbourhood—where a housing emergency and a population at risk of residential exclusion meet a degraded historic housing stock mainly consisting of multi-family, privately owned buildings—provides a wonderful pretext to locally address these global challenges.

The design of small-scale, low cost, standardised solutions does not only respond to global sustainability and affordability needs; it also meets specific local needs for heritage preservation and urgent self-manageable action in the short term. The proposed socio-architectural transformations are adaptable, replicable, and can have an impact on different levels and in contexts far beyond the pilot cases.

Proposed solutions are based on the capacity of local professionals, non-profit entities and residents to reach consensus and implement affordable, sustainable and replicable solutions co-designed with the help of applied academic research in architecture. The integral, scalable nature of this methodology is key to providing local answers to the exposed global challenges.

In parallel, the field of architecture is experiencing a turn towards more collaborative and socially responsible practices that enhance citizen participation and empowerment and foster cohabitation and mutual support. The urgent need to improve quality of life in multi-family-housing in vulnerable urban communities can only be effectively approached through this transversal and collaborative approach to design.

Barcelona’s Raval neighbourhood—where a housing emergency and a population at risk of residential exclusion meet a degraded historic housing stock mainly consisting of multi-family, privately owned buildings—provides a wonderful pretext to locally address these global challenges.

The design of small-scale, low cost, standardised solutions does not only respond to global sustainability and affordability needs; it also meets specific local needs for heritage preservation and urgent self-manageable action in the short term. The proposed socio-architectural transformations are adaptable, replicable, and can have an impact on different levels and in contexts far beyond the pilot cases.

Proposed solutions are based on the capacity of local professionals, non-profit entities and residents to reach consensus and implement affordable, sustainable and replicable solutions co-designed with the help of applied academic research in architecture. The integral, scalable nature of this methodology is key to providing local answers to the exposed global challenges.

Learning transferred to other parties

The methodology of this project was designed to be applicable in vastly different residential contexts and in communities facing management, economic and technical difficulties. The participative design of a catalogue of solutions provides ready-made, open designs that could be adapted and implemented in most multi-family historic buildings in the Raval neighbourhood or in similar contexts (Mediterranean historic centres and other vulnerable, existing multi-family buildings).

Previous fieldwork and research show that close to 40% of entryways in residential buildings in the Raval lack basic ventilation and natural light. About half of buildings in the neighbourhood have serious technical and spatial impediments to adding lifts and require improvements in the safety and accessibility of staircases. Almost all shared rooves are misused and lack adequate, safe, comfortable spaces. These are spaces where the pilot projects could be replicated as soon as they are adapted to meet the residents’ needs and desires.

The replicability and adaptability of the projects have already been tested in the pilot interventions. Different adaptations of the same open-system pergola were implemented on two community rooves, while the interior air quality of two staircases was improved through the implementation of the same micro-projects in entryways and staircase openings.

On a global level, the common ties formed between public administrations, academics (researchers and students), non-profits and civil society (neighbourhood associations and communities) allow for capacity building and the dissemination of the results and the technology used. The project will soon be exposed in a massive online, open course within an Erasmus+ project, and it will be part of the Barcelona City Council’s science sharing program and the UPC’s citizen science program.

Previous fieldwork and research show that close to 40% of entryways in residential buildings in the Raval lack basic ventilation and natural light. About half of buildings in the neighbourhood have serious technical and spatial impediments to adding lifts and require improvements in the safety and accessibility of staircases. Almost all shared rooves are misused and lack adequate, safe, comfortable spaces. These are spaces where the pilot projects could be replicated as soon as they are adapted to meet the residents’ needs and desires.

The replicability and adaptability of the projects have already been tested in the pilot interventions. Different adaptations of the same open-system pergola were implemented on two community rooves, while the interior air quality of two staircases was improved through the implementation of the same micro-projects in entryways and staircase openings.

On a global level, the common ties formed between public administrations, academics (researchers and students), non-profits and civil society (neighbourhood associations and communities) allow for capacity building and the dissemination of the results and the technology used. The project will soon be exposed in a massive online, open course within an Erasmus+ project, and it will be part of the Barcelona City Council’s science sharing program and the UPC’s citizen science program.

Keywords

Guided self-rehabilitation

Improving living conditions

Community-led design

Perfectible rehabilitation

Vulnerable multi-family communities