Reconnecting with nature

Chozos

Chozos - Humans and nature in harmony

“Chozos” is a collaborative educational project between Extremadura (Spain) and Baden-Württemberg (Germany) aiming to value and regain fading traditions, bioconstruciton, and tacit skills. The chozo, a traditional shepherd’s hut built entirely with nature-based solutions, reflects an architecture fully connected with its environment. As the starting point of the joint project, it triggers local involvement, reorientation towards ecological practices, and inclusion across generations and cultures

Spain

Local

Cabeza del Buey, a rural village in southern Spain, and Stuttgart, an industrialized city in western Germany.

It addresses urban-rural linkages

It refers to other types of transformations (soft investment)

Yes

2023-03-31

No

No

No

As an individual partnership with other persons/organisation(s)

“Chozos” is a transdisciplinary project exploring, preserving, and transferring the fading knowledge of traditional building techniques using natural materials, aiding in the rethinking of construction systems that help to reduce the ecological footprint of future projects. By reviving vernacular architecture in extinction, the project highlights the importance of awareness, care, community, craftsmanship, and harmony between nature and human beings.

To deepen this understanding, two ecologically handcrafted chozos (traditional shepherds’ huts

were co-built) demonstrating how reconnecting with nature means recognizing resources as finite and construction as an inherently extractive act. In a society distanced from the origin of materials and lost in production chains, the chozo offers a direct connection to what is taken and what is left. This simple yet powerful structure exemplifies a construction logic that respects mutual needs and minimizes environmental impact, raising awareness of how architecture is shaped by both material and immaterial surroundings.

Beyond simply "re-creating" the chozos, the project focused on "co-creating" them, integrating context, history, local knowledge, and material realities. For this reason, the process included an intense exchange and a mutual learning with shepherds, local people, various experts, students and teachers. The holistic approach of the project was promoting inter-generational dialogue with the focus on the collection of perceptions, experiences, and narratives from the past and from the current situation.

During the two-week workshop on-site, participants, local inhabitants, and guests, were experiencing awareness for sustainable way of living in co-existing with the nature. From the two co-built chozos, one remains in Cabeza del Buey as an educational tool for school classes. The second one was travelling to Germany and staying in Switzerland opening a cross-cultural debate.

To deepen this understanding, two ecologically handcrafted chozos (traditional shepherds’ huts

were co-built) demonstrating how reconnecting with nature means recognizing resources as finite and construction as an inherently extractive act. In a society distanced from the origin of materials and lost in production chains, the chozo offers a direct connection to what is taken and what is left. This simple yet powerful structure exemplifies a construction logic that respects mutual needs and minimizes environmental impact, raising awareness of how architecture is shaped by both material and immaterial surroundings.

Beyond simply "re-creating" the chozos, the project focused on "co-creating" them, integrating context, history, local knowledge, and material realities. For this reason, the process included an intense exchange and a mutual learning with shepherds, local people, various experts, students and teachers. The holistic approach of the project was promoting inter-generational dialogue with the focus on the collection of perceptions, experiences, and narratives from the past and from the current situation.

During the two-week workshop on-site, participants, local inhabitants, and guests, were experiencing awareness for sustainable way of living in co-existing with the nature. From the two co-built chozos, one remains in Cabeza del Buey as an educational tool for school classes. The second one was travelling to Germany and staying in Switzerland opening a cross-cultural debate.

bioconstruction

vernacular architecture

rural heritage

sustainable cohabitation

intergenerational learning

The chozos are an expression of an architecture that was created in a symbiosis of cultural and natural conditions. Therefore, a deep understanding of sustainability was the initial point for the research and the pedagogy of this project:

_environment: The huts can be erected relatively simply, autonomously and with few local materials. A traditional method of building and using only few local natural materials has a minimal footprint in the landscape.

_community: Understanding chozos as a collective experience allows for strengthening local identity and for showing visitors that there are some universal things all people have in common. Daily discussions, working together and also celebrating together are creating a sense of community.

_knowledge transfer: This original vernacular architecture contains a great deal of knowledge that is in danger of being lost: the use of local resources, the effective use of materials, integration into the landscape, respect for the built environment, understanding life-cycle of material.

_afterlife – Since the huts were constructed using nature-based solutions and low-impact construction, they can, on one hand be reused, recicled, or adapted to new situations, and on the other, leave only a small footprint on the environment. This approach promotes constant awareness on the extractive nature of construction and the responsibility to take care of the two sides of the coin, and the responsibility to care for both sides of the equation: what is taken and what is left behind.

_environment: The huts can be erected relatively simply, autonomously and with few local materials. A traditional method of building and using only few local natural materials has a minimal footprint in the landscape.

_community: Understanding chozos as a collective experience allows for strengthening local identity and for showing visitors that there are some universal things all people have in common. Daily discussions, working together and also celebrating together are creating a sense of community.

_knowledge transfer: This original vernacular architecture contains a great deal of knowledge that is in danger of being lost: the use of local resources, the effective use of materials, integration into the landscape, respect for the built environment, understanding life-cycle of material.

_afterlife – Since the huts were constructed using nature-based solutions and low-impact construction, they can, on one hand be reused, recicled, or adapted to new situations, and on the other, leave only a small footprint on the environment. This approach promotes constant awareness on the extractive nature of construction and the responsibility to take care of the two sides of the coin, and the responsibility to care for both sides of the equation: what is taken and what is left behind.

Architecture as a cultural practice demonstrates how "Gestasltung“ can enhance human experience and social enrichment. It implies an understanding of aesthetics as a result of the understanding of local practices, knowledge, and resources. As Rudofsky (1964) notes, vernacular architecture reflects the essence of “how to live and let live” on both local and universal scales. Its beauty lies in its ability to solve practical problems through a sensitive interplay of context, culture, and identity.

The construction of two chozos embodied these qualities, blending social values (practices), and technological ingenuity (knowledge), and environmental principles (resources). The project celebrated the aesthetics and experiential richness of vernacular building methods by co-creating architectures that connect past and present, architecture and environment, bridging cultural knowledge with sustainable practices.

During the workshop, participants reimagined the chozos as living heritage, deeply connected with their landscape and oral histories. These structures symbolized a cultural imaginary that had always surrounded them. Simultaneously, the chozos demonstrated untapped architectural potential, showcasing how the “philosophy and knowledge of the anonymous builders” offers a “source of architectural inspiration for the industrial human being,” as Rudofsky again observed.

Through the co-creation process, aesthetics became a tool for inclusion and education. Participants experienced firsthand the cultural and environmental benefits of traditional building techniques, fostering a sense of identity and shared ownership. By celebrating a complex spatial expression that is based on local knowledge, practices, materials and therefore a specific local form, the project provided an opportunity for cultural reflection and a vision of how ancient wisdom can inspire modern, design. This approach demonstrates how architecture can be a profound vehicle to make a better world

The construction of two chozos embodied these qualities, blending social values (practices), and technological ingenuity (knowledge), and environmental principles (resources). The project celebrated the aesthetics and experiential richness of vernacular building methods by co-creating architectures that connect past and present, architecture and environment, bridging cultural knowledge with sustainable practices.

During the workshop, participants reimagined the chozos as living heritage, deeply connected with their landscape and oral histories. These structures symbolized a cultural imaginary that had always surrounded them. Simultaneously, the chozos demonstrated untapped architectural potential, showcasing how the “philosophy and knowledge of the anonymous builders” offers a “source of architectural inspiration for the industrial human being,” as Rudofsky again observed.

Through the co-creation process, aesthetics became a tool for inclusion and education. Participants experienced firsthand the cultural and environmental benefits of traditional building techniques, fostering a sense of identity and shared ownership. By celebrating a complex spatial expression that is based on local knowledge, practices, materials and therefore a specific local form, the project provided an opportunity for cultural reflection and a vision of how ancient wisdom can inspire modern, design. This approach demonstrates how architecture can be a profound vehicle to make a better world

The “Chozos” project prioritizes inclusion through accessibility, affordability, and collaborative participation. The building site was open to all, enabling active participation from diverse community members, including villagers of various ages, who were invited via personal outreach or social media. During our week we got a visit from curious individuals, but also from the elder care house and the local schools. By fostering a welcoming, multilingual environment in Spanish, German, and English, the project ensured effective communication and inclusivity.

Another objective was to challenge the historical stigma surrounding chozos and the loss of vernacular building techniques. By amplifying the voices of those who once lived in these structures, the project reclaimed their value as sustainable, self-managed, and affordable homes. Traditionally seen as symbols of poverty and immorality under the fascist regime—which promoted modernization while disregarding traditional knowledge—the project aimed to reintegrate and celebrate these construction methods. This approach highlights their relevance in addressing contemporary challenges while preserving cultural identity and environmental harmony.

Through the open and co-creative processes, the project strengthened intergenerational and cross-cultural dialogue. This inclusion fosters ownership, skill-sharing, and community cohesion while promoting the chozos as a dignified, ecological model that may help to address current trials. Inspiring new societal models grounded in equality, sustainability, and cultural pride. Its inclusive approach offers a replicable framework for affordable housing solutions, bridging tradition and innovation to benefit vulnerable communities while celebrating shared heritage.

Another objective was to challenge the historical stigma surrounding chozos and the loss of vernacular building techniques. By amplifying the voices of those who once lived in these structures, the project reclaimed their value as sustainable, self-managed, and affordable homes. Traditionally seen as symbols of poverty and immorality under the fascist regime—which promoted modernization while disregarding traditional knowledge—the project aimed to reintegrate and celebrate these construction methods. This approach highlights their relevance in addressing contemporary challenges while preserving cultural identity and environmental harmony.

Through the open and co-creative processes, the project strengthened intergenerational and cross-cultural dialogue. This inclusion fosters ownership, skill-sharing, and community cohesion while promoting the chozos as a dignified, ecological model that may help to address current trials. Inspiring new societal models grounded in equality, sustainability, and cultural pride. Its inclusive approach offers a replicable framework for affordable housing solutions, bridging tradition and innovation to benefit vulnerable communities while celebrating shared heritage.

The field of agriculture connected on-site natural and social systems, creating complex interdependencies among involved actors. To fully grasp this system, it was essential to engage with those affected. That’s why the working site remained open to anyone interested.

The project sparked great participation and curiosity among locals. Visitors from the senior residence, schools, shepherds, locals, Germans living in Extremadura, and Extremadurans in Germany came on their own initiative. These encounters led to exchange: locals, seeing external appreciation for something once considered archaic, felt a renewed sense of pride in their culture. Older generations recognized their past in the chozo and shared stories, while younger ones saw one for the first time. The exchange extended beyond local interactions. For participants from Stuttgart, it was deeply moving to witness knowledge being passed from aging shepherds to students, and from students to the village children—creating a chain that bridged past and future, as well as different cultural backgrounds.

Even after the project’s completion, dialogue with locals and participants continues. As we work on a book documenting the initiative, we have had the opportunity to reconnect with people two years later, gathering reflections on its impact. The project is still remembered in the village, with many locals expressing a desire for similar initiatives. In a rural area facing depopulation, they emphasize the importance of communal activities in strengthening identity and belonging.

Some now view the chozos as part of their heritage, something that truly belongs to them. Many are astonished that one of the chozos made its way to Switzerland and are fascinated by photos of it standing strong under the snow, adapting to a completely different climate. The mayorness believes that the project has brought excitement and hope to a community where young people often leave in search of better opportunities.

The project sparked great participation and curiosity among locals. Visitors from the senior residence, schools, shepherds, locals, Germans living in Extremadura, and Extremadurans in Germany came on their own initiative. These encounters led to exchange: locals, seeing external appreciation for something once considered archaic, felt a renewed sense of pride in their culture. Older generations recognized their past in the chozo and shared stories, while younger ones saw one for the first time. The exchange extended beyond local interactions. For participants from Stuttgart, it was deeply moving to witness knowledge being passed from aging shepherds to students, and from students to the village children—creating a chain that bridged past and future, as well as different cultural backgrounds.

Even after the project’s completion, dialogue with locals and participants continues. As we work on a book documenting the initiative, we have had the opportunity to reconnect with people two years later, gathering reflections on its impact. The project is still remembered in the village, with many locals expressing a desire for similar initiatives. In a rural area facing depopulation, they emphasize the importance of communal activities in strengthening identity and belonging.

Some now view the chozos as part of their heritage, something that truly belongs to them. Many are astonished that one of the chozos made its way to Switzerland and are fascinated by photos of it standing strong under the snow, adapting to a completely different climate. The mayorness believes that the project has brought excitement and hope to a community where young people often leave in search of better opportunities.

The Chozos project engaged stakeholders at multiple levels, fostering knowledge exchange and collaboration.

At the local level, architect Alba Balmaseda, in collaboration with the Faculty of Architecture and Planning, University of Stuttgart, initiated the project, involving students and tutors from IRGE and SuE Institutes. The Municipality of Cabeza del Buey provided logistical support, while shepherds, bioconstruction experts, neighbors, and schools contributed materials, skills, and site access. Community participation was encouraged through social media and direct outreach.

At the regional level, media coverage in Spain and Germany amplified the project’s impact, sparking discussions on vernacular architecture. Local networks played a key role in preparing materials, as sourcing and processing natural resources required pre-planning.

At the national level, Germany’s Sto-Stiftung funded student mobility, supporting hands-on learning and cultural exchange. In Spain, the Spanish Embassy in Switzerland helped gain recognition, enabling participation in international exhibitions.

At the European level, the project was featured at the Tacit Knowledge conference and exhibition in Switzerland, positioning the chozo as a case study in sustainable architecture. Collaboration between Spain, Germany, and Italy enriched both research and construction.

Stakeholders engaged in three phases: theoretical research at the University of Stuttgart, on-site cultural immersion in Cabeza del Buey—including visits to preserved chozos and local traditions—and the construction phase, where students worked with local experts and shepherds to integrate traditional techniques.

This multi-level engagement revitalized a nearly lost architectural practice, fostering a shared sense of ownership between local communities and international participants. The project stands as a model for interdisciplinary, cross-cultural collaboration in sustainable architecture.

At the local level, architect Alba Balmaseda, in collaboration with the Faculty of Architecture and Planning, University of Stuttgart, initiated the project, involving students and tutors from IRGE and SuE Institutes. The Municipality of Cabeza del Buey provided logistical support, while shepherds, bioconstruction experts, neighbors, and schools contributed materials, skills, and site access. Community participation was encouraged through social media and direct outreach.

At the regional level, media coverage in Spain and Germany amplified the project’s impact, sparking discussions on vernacular architecture. Local networks played a key role in preparing materials, as sourcing and processing natural resources required pre-planning.

At the national level, Germany’s Sto-Stiftung funded student mobility, supporting hands-on learning and cultural exchange. In Spain, the Spanish Embassy in Switzerland helped gain recognition, enabling participation in international exhibitions.

At the European level, the project was featured at the Tacit Knowledge conference and exhibition in Switzerland, positioning the chozo as a case study in sustainable architecture. Collaboration between Spain, Germany, and Italy enriched both research and construction.

Stakeholders engaged in three phases: theoretical research at the University of Stuttgart, on-site cultural immersion in Cabeza del Buey—including visits to preserved chozos and local traditions—and the construction phase, where students worked with local experts and shepherds to integrate traditional techniques.

This multi-level engagement revitalized a nearly lost architectural practice, fostering a shared sense of ownership between local communities and international participants. The project stands as a model for interdisciplinary, cross-cultural collaboration in sustainable architecture.

The Chozos project was built on a multidisciplinary and participatory approach, integrating expertise from academia, local communities, and practitioners.

The University of Stuttgart contributed knowledge in architectural scale (Institute IRGE), urban studies (Institute SuE), and social sciences, providing a framework for understanding spatial, social, and environmental dimensions. Meanwhile, locals and shepherds were central to the ethnographic expertise, bringing in stories, know-how, objects, and tacit knowledge essential to the project’s authenticity and success.

From the very beginning, all actors were actively involved and encouraged to participate in project development and decision-making. There was a continuous exchange of perspectives and ideas, ensuring that all knowledge resources were integrated into the process.

A local group of bio-construction experts played a key role in organizing material collection, storage, and the building process of the two chozos. Additionally, researchers on cohabitation introduced a new perspective, explaining the relationship between animals and human spaces, shifting the anthropocentric view of architecture. The Municipal Environmental Officer of Cabeza del Buey guided the team through the local ecological system and biodiversity, providing expertise that enriched the project’s environmental awareness.

This collaborative and cross-disciplinary approach ensured that the Chozos project was not just a reconstruction of traditional architecture but a holistic exploration of sustainable and culturally rooted living practices.

The University of Stuttgart contributed knowledge in architectural scale (Institute IRGE), urban studies (Institute SuE), and social sciences, providing a framework for understanding spatial, social, and environmental dimensions. Meanwhile, locals and shepherds were central to the ethnographic expertise, bringing in stories, know-how, objects, and tacit knowledge essential to the project’s authenticity and success.

From the very beginning, all actors were actively involved and encouraged to participate in project development and decision-making. There was a continuous exchange of perspectives and ideas, ensuring that all knowledge resources were integrated into the process.

A local group of bio-construction experts played a key role in organizing material collection, storage, and the building process of the two chozos. Additionally, researchers on cohabitation introduced a new perspective, explaining the relationship between animals and human spaces, shifting the anthropocentric view of architecture. The Municipal Environmental Officer of Cabeza del Buey guided the team through the local ecological system and biodiversity, providing expertise that enriched the project’s environmental awareness.

This collaborative and cross-disciplinary approach ensured that the Chozos project was not just a reconstruction of traditional architecture but a holistic exploration of sustainable and culturally rooted living practices.

It does not happen very often that a small, single hut will be a main object of research. But it can be used as a starting point to think about the canonical knowledge and give an inspiration how the architecture can be understood as a social tool to make the world better and sustainable. Putting the shepherds as a main source for learning about the traditions, local natural materials and skills was another unique characteristic. “Chozos” is a platform for a reflection of a way of life. It aims for encouraging us to strengthen the awareness of a rich cultural heritage and to use it for social and technical innovations leading to a better life in an intergenerational dialogue.

Two weeks of intensive exchange, living in the village, participating on the local festival was a common ground for an inclusive design. While one chozo was rebuilt according to traditional way of construction, a second chozo intended to use a different construction technique as the “original”. The modular chozo was experimenting with a construction, which is more flexible and can be adapted to local materials in another context. The modularity is allowing to dismantle the chozo in a simple way, stack the modules for the transport.

Raising awareness of the importance of sustainable development was not limited to one place. The modular chozo was travelling through Europa to be exhibited in Stuttgart and in Zürich.

Two weeks of intensive exchange, living in the village, participating on the local festival was a common ground for an inclusive design. While one chozo was rebuilt according to traditional way of construction, a second chozo intended to use a different construction technique as the “original”. The modular chozo was experimenting with a construction, which is more flexible and can be adapted to local materials in another context. The modularity is allowing to dismantle the chozo in a simple way, stack the modules for the transport.

Raising awareness of the importance of sustainable development was not limited to one place. The modular chozo was travelling through Europa to be exhibited in Stuttgart and in Zürich.

The methodology of our project was based on the methods and phases of transdisciplinary research: “Understanding,” “Concept developing,” “Implementation” and “Reflection & Evaluation”. In each of those phases, we put a special focus on 3 parameters: (1) process & actions, (2) actors, and (3) exchange & integration. In the processes of co-creation we were using participative methods like: design-thinking, mock-up, anthropological method of observing.

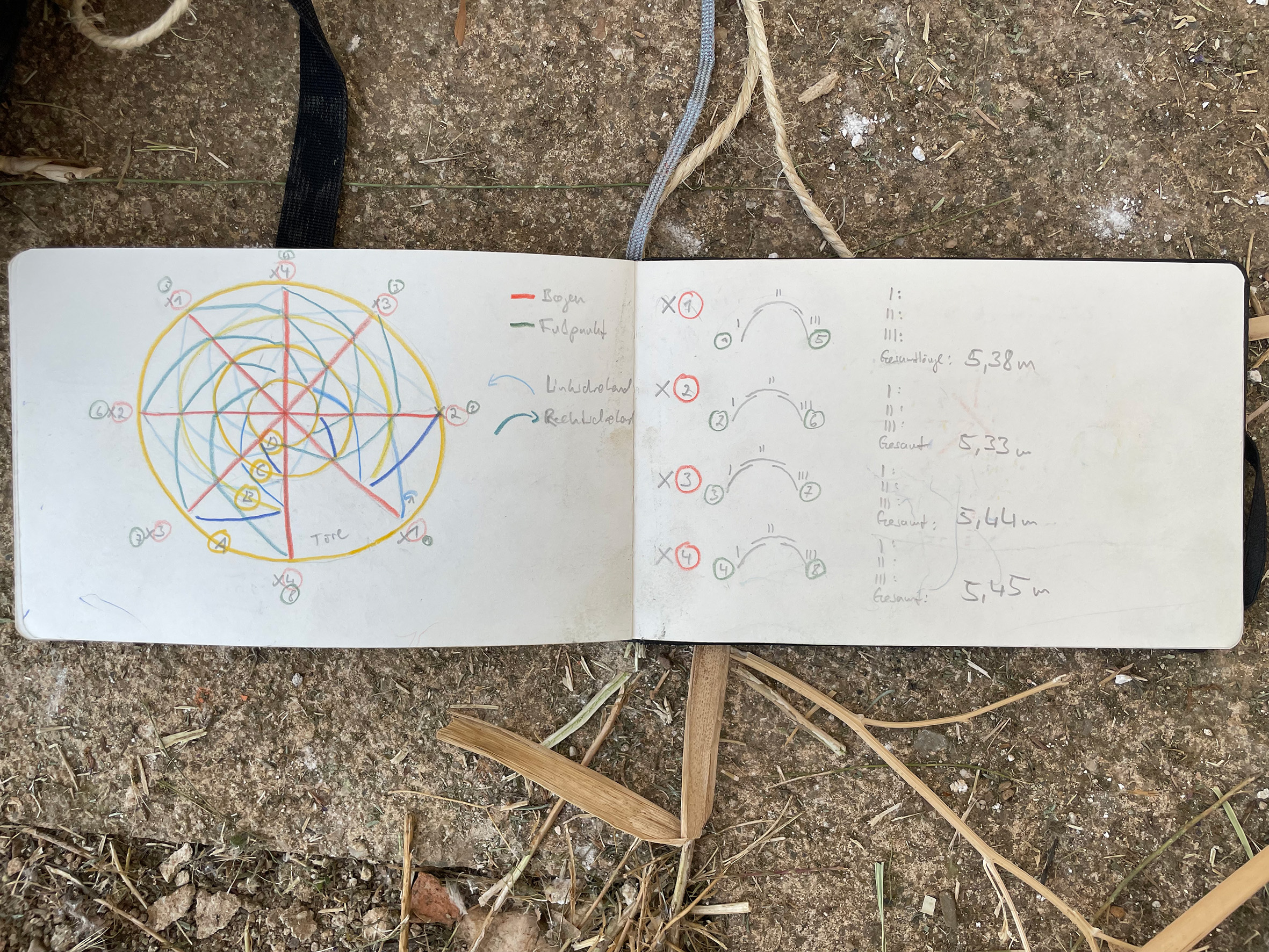

The process of building the chozo-object: first we take into account the where, the why and the how. The natural and cultural context is studied: the landscape, the tradition of transhumance, the culture of the huts, the challenges of the present. We then proceed to the construction of two huts on a scale of 1:1, accompanied by different local actors. We pay attention to the processes in order to be able to describe a posteriori the steps to follow to build a hut if someone else wanted to do it, given that knowledge is being lost: detailing the necessary materials, where we can find them in nature, what they are called, what they look like; collecting the tools necessary for their construction; finding a narrative for the process of building the hut, the setting out, the construction of the feet, the rings and arches, the placement of the enclosure, the types of knots, etc. In the actors' block, we wanted to give a voice to the people involved in the process. We understand the construction of the 1:1 scale hut as a social process in which different agents intervene, constructing not only the object itself, but also a whole transversal and multi-scale knowledge. The space was always open to visit or participate. To this end, we promoted on-site interviews, as well as questionnaires that invite reflection on architecture as a cultural project. To ensure exchange, contacts were established with the existing community, inviting them to participate in the initiative and always leaving the doors open to the building site,

The process of building the chozo-object: first we take into account the where, the why and the how. The natural and cultural context is studied: the landscape, the tradition of transhumance, the culture of the huts, the challenges of the present. We then proceed to the construction of two huts on a scale of 1:1, accompanied by different local actors. We pay attention to the processes in order to be able to describe a posteriori the steps to follow to build a hut if someone else wanted to do it, given that knowledge is being lost: detailing the necessary materials, where we can find them in nature, what they are called, what they look like; collecting the tools necessary for their construction; finding a narrative for the process of building the hut, the setting out, the construction of the feet, the rings and arches, the placement of the enclosure, the types of knots, etc. In the actors' block, we wanted to give a voice to the people involved in the process. We understand the construction of the 1:1 scale hut as a social process in which different agents intervene, constructing not only the object itself, but also a whole transversal and multi-scale knowledge. The space was always open to visit or participate. To this end, we promoted on-site interviews, as well as questionnaires that invite reflection on architecture as a cultural project. To ensure exchange, contacts were established with the existing community, inviting them to participate in the initiative and always leaving the doors open to the building site,

The disconnection with nature continue to be abandoned due to global discourses on urbanization, leading to the loss of knowledge deeply rooted in environmental awareness and resource management. This phenomenon is not unique to Extremadura but is occurring across many European regions. In this sense, the replicability of the Chozos project is possible, as similar rural realities exist throughout Europe and World-Wide.

One clear avenue for replication is in transhumance regions, where specific architectural forms and knowledge systems have developed around livestock migration. Countries such as Slovenia, Armenia, Ireland, Italy, and Greece maintain strong connections to their land through herding traditions, making them ideal locations for similar projects. Ultimately, the initiative demonstrates how simple, functional constructions can serve as a unifying element between different actors, strengthening social and environmental ties by recognizing and valuing their cultural significance.

Time is a crucial factor, as the generations holding this knowledge are gradually disappearing. Traditionally passed down through oral transmission and hands-on practice, this tacit knowledge is at risk of being lost. Our experience has shown that bringing together different countries, cultures, and realities fosters meaningful exchanges. Locals have gained a renewed appreciation for their heritage upon seeing external interest, while participants from abroad have discovered new perspectives, reshaping how they engage with their own surroundings.

To further this effort, a European network on traditional and sustainable rural architecture could facilitate knowledge exchange, interdisciplinary research, and collaborative hands-on experiences. Connecting experts, institutions, and communities across Europe would help safeguard disappearing practices while fostering innovation in sustainability, bioco

One clear avenue for replication is in transhumance regions, where specific architectural forms and knowledge systems have developed around livestock migration. Countries such as Slovenia, Armenia, Ireland, Italy, and Greece maintain strong connections to their land through herding traditions, making them ideal locations for similar projects. Ultimately, the initiative demonstrates how simple, functional constructions can serve as a unifying element between different actors, strengthening social and environmental ties by recognizing and valuing their cultural significance.

Time is a crucial factor, as the generations holding this knowledge are gradually disappearing. Traditionally passed down through oral transmission and hands-on practice, this tacit knowledge is at risk of being lost. Our experience has shown that bringing together different countries, cultures, and realities fosters meaningful exchanges. Locals have gained a renewed appreciation for their heritage upon seeing external interest, while participants from abroad have discovered new perspectives, reshaping how they engage with their own surroundings.

To further this effort, a European network on traditional and sustainable rural architecture could facilitate knowledge exchange, interdisciplinary research, and collaborative hands-on experiences. Connecting experts, institutions, and communities across Europe would help safeguard disappearing practices while fostering innovation in sustainability, bioco

_Climate Change: The project promotes the use of natural materials sourced on-site, reducing the carbon footprint associated with industrialized construction. This approach ensures that human development aligns with finite environmental resources, advocating for a necessary return to local, renewable materials, a practice still common in many parts of the world.

_Think global – Act local: By utilizing local craftsmanship and knowledge, the project proves that small-scale, community-driven solutions serve as living laboratories for future innovations. The transformation towards sustainability must begin at the local level, building on existing knowledge while integrating modern techniques to ensure resilience.

_Rural depopulation, knowledge gap and quality of life: By reincorporating fading traditions and local expertise, the project strengthens rural communities facing depopulation. It provides a framework for intergenerational knowledge exchange, where older generations pass down traditional skills, ensuring that young people see rural life as an opportunity rather than a limitation. This fosters a renewed sense of identity and purpose in these areas.

_Back to Basics - The Chozos project reintroduces historic, low-impact building techniques, proving their relevance in modern sustainability efforts. By adapting vernacular architecture to current needs, it serves as a model for other regions looking to revive contextual and resource-efficient building methods.

_Ecological and Cultural Responsibility in Architecture: The Chozos project demonstrates architecture and urbanism as a process informed by ecological and cultural responsibility. Its methodology aligns with a growing movement of 1:1 scale activities in schools of architecture and urbanism, where education should foster experiences in which local knowledge, materials, and practices inform sustainable solutions, ensuring a more resilient and context-aware built environment.

_Think global – Act local: By utilizing local craftsmanship and knowledge, the project proves that small-scale, community-driven solutions serve as living laboratories for future innovations. The transformation towards sustainability must begin at the local level, building on existing knowledge while integrating modern techniques to ensure resilience.

_Rural depopulation, knowledge gap and quality of life: By reincorporating fading traditions and local expertise, the project strengthens rural communities facing depopulation. It provides a framework for intergenerational knowledge exchange, where older generations pass down traditional skills, ensuring that young people see rural life as an opportunity rather than a limitation. This fosters a renewed sense of identity and purpose in these areas.

_Back to Basics - The Chozos project reintroduces historic, low-impact building techniques, proving their relevance in modern sustainability efforts. By adapting vernacular architecture to current needs, it serves as a model for other regions looking to revive contextual and resource-efficient building methods.

_Ecological and Cultural Responsibility in Architecture: The Chozos project demonstrates architecture and urbanism as a process informed by ecological and cultural responsibility. Its methodology aligns with a growing movement of 1:1 scale activities in schools of architecture and urbanism, where education should foster experiences in which local knowledge, materials, and practices inform sustainable solutions, ensuring a more resilient and context-aware built environment.

_Results: The "Chozos" project has achieved tangible outcomes, engaging both direct and indirect beneficiaries at local, national, and European levels. Two architectural objects were built: The traditional chozo remains in Cabeza del Buey as an educational tool; The modular reinterpretation travels across Europe, fostering dialogue and debate.

_Outcome: As described before, the "Chozos" project fostered both local and international engagement, with locals, shepherds, and visitors actively participating in the process. The involvement of civil society was key to ensuring the integration of knowledge across generations and disciplines. Locals played an active role, providing materials, skills, and historical insights. Shepherds shared tacit knowledge, contributing their expertise on vernacular construction and resource use, while younger villagers engaged by observing and learning from the process. Students acted as a "link" of knowledge. Following the experience, students were interviewed and expressed how it made them realize their disconnection from nature: “People here know how to use nature as a resource, understanding its rhythm and properties. My life is not connected enough with nature to use it as they do.” At the same time, the project prompted them to question their own models and acknowledge that the experience will shape their future designs.“Experiencing a different way of life offers new perspectives. It makes you question your own model and opens new design possibilities, especially in the face of climate change,”or “I’ve worked with traditional building methods, but mostly in massive construction. The chozo, however, is lightweight and minimalistic, using only essential materials. This will influence my future studies.”

_Impact: A major milestone was the project’s selection for the TACK Community’s final conference “Tacit Knowledge in Architecture” and the exhibition “Unausgesprochenes Wissen” at ETH Zurich (June 2023).

_Outcome: As described before, the "Chozos" project fostered both local and international engagement, with locals, shepherds, and visitors actively participating in the process. The involvement of civil society was key to ensuring the integration of knowledge across generations and disciplines. Locals played an active role, providing materials, skills, and historical insights. Shepherds shared tacit knowledge, contributing their expertise on vernacular construction and resource use, while younger villagers engaged by observing and learning from the process. Students acted as a "link" of knowledge. Following the experience, students were interviewed and expressed how it made them realize their disconnection from nature: “People here know how to use nature as a resource, understanding its rhythm and properties. My life is not connected enough with nature to use it as they do.” At the same time, the project prompted them to question their own models and acknowledge that the experience will shape their future designs.“Experiencing a different way of life offers new perspectives. It makes you question your own model and opens new design possibilities, especially in the face of climate change,”or “I’ve worked with traditional building methods, but mostly in massive construction. The chozo, however, is lightweight and minimalistic, using only essential materials. This will influence my future studies.”

_Impact: A major milestone was the project’s selection for the TACK Community’s final conference “Tacit Knowledge in Architecture” and the exhibition “Unausgesprochenes Wissen” at ETH Zurich (June 2023).