Reconnecting with nature

Park on the Warsaw Uprising Mound

Fourth Nature Park on the Warsaw Uprising Mound in Warsaw, Poland

The Warsaw Uprising Mound is a rewilded urban enclave on a former landfill, once a dumping site for post-WWII rubble. Over decades, it formed a 40-metre hill, later overgrown with vegetation that became a ruderal forest. The site was adapted into a public park, highlighting its ecological and symbolic potential. The Mound was thus reclaimed in three ways: by nature, symbolically, and physically by integrating the rubble into design. Once inaccessible and dangerous, it is now bustling with life.

Poland

Local

Warsaw

Mainly urban

It refers to a physical transformation of the built environment (hard investment)

Yes

2024-06-21

Yes

ERDF : European Regional Development Fund

No

No

As a representative of an organisation, in partnership with other organisations

The Warsaw Uprising Mound Park project transformed a post-war rubble landfill into a regenerative urban space that reconnects communities with nature while preserving cultural heritage. It integrates ecological restoration, inclusive design, and historical memory, demonstrating how degraded landscapes can become hubs of biodiversity and social resilience. The key objectives of the project included ecological regeneration by revitalizing biodiversity and restoring natural cycles through rewilding and native species, social inclusion by creating an accessible public space for diverse communities, cultural memory preservation by repurposing wartime rubble to symbolize resilience and history, and sustainable practices by reusing 90% of site materials to minimize waste and carbon footprint. The ecological aspect is seen in creating a biodiverse landscape with meadows, forests, and water retention systems that nurture life. The social dimension manifests in inclusive park infrastructure and participatory engagement of residents, fostering a sense of belonging and collective responsibility. The cultural significance is embodied in the Lapidarium and the use of rubble concrete, "Warsaw urbanite", which links history with ecological renewal, allowing past and future to coexist in a meaningful narrative. Philosophically, the park challenges conventional aesthetics by embracing dynamic, self-sustaining ecosystems and encourages visitors to become stewards of their environment. The Warsaw Uprising Mound Park serves as a global model for urban regeneration, proving that even sites of destruction can foster hope, equity, and ecological sustainability, embodying the principles of beauty, goodness, and truth.

ruderal ecosystems

biodiversity

circular economy

local identity

inclusive design

The park project showcases sustainability through ecological restoration, biodiversity enhancement and circular material use. Once a post-war rubble landfill, the site has been transformed into a biodiverse urban park using nature-based solutions, prioritizing minimal intervention to let natural processes guide regeneration.

A key focus was ecological restoration. Water and soil management stabilized the site. Hundreds of meters of low fascine fences were installed to combat erosion, retain organic matter, and foster soil formation. A multi-point water retention system turned runoff into a resource, protecting hydrology and reducing degradation. Certain areas were left inaccessible to protect wildlife. Artificial lighting was reduced to support nocturnal species.

Native species were introduced to boost biodiversity, while pioneer vegetation that naturally colonized the site was integrated into the restoration. The landscape was designed to evolve naturally, maintaining its wild, self-sustaining character with plantings that blend seamlessly into existing vegetation. Phytosociological studies guided plant selection, ensuring ecological compatibility. More than 70,000 plants were planted. In the future, planted young forest saplings will replace invasive ruderal trees, allowing natural selection to shape the woodland ecosystem.

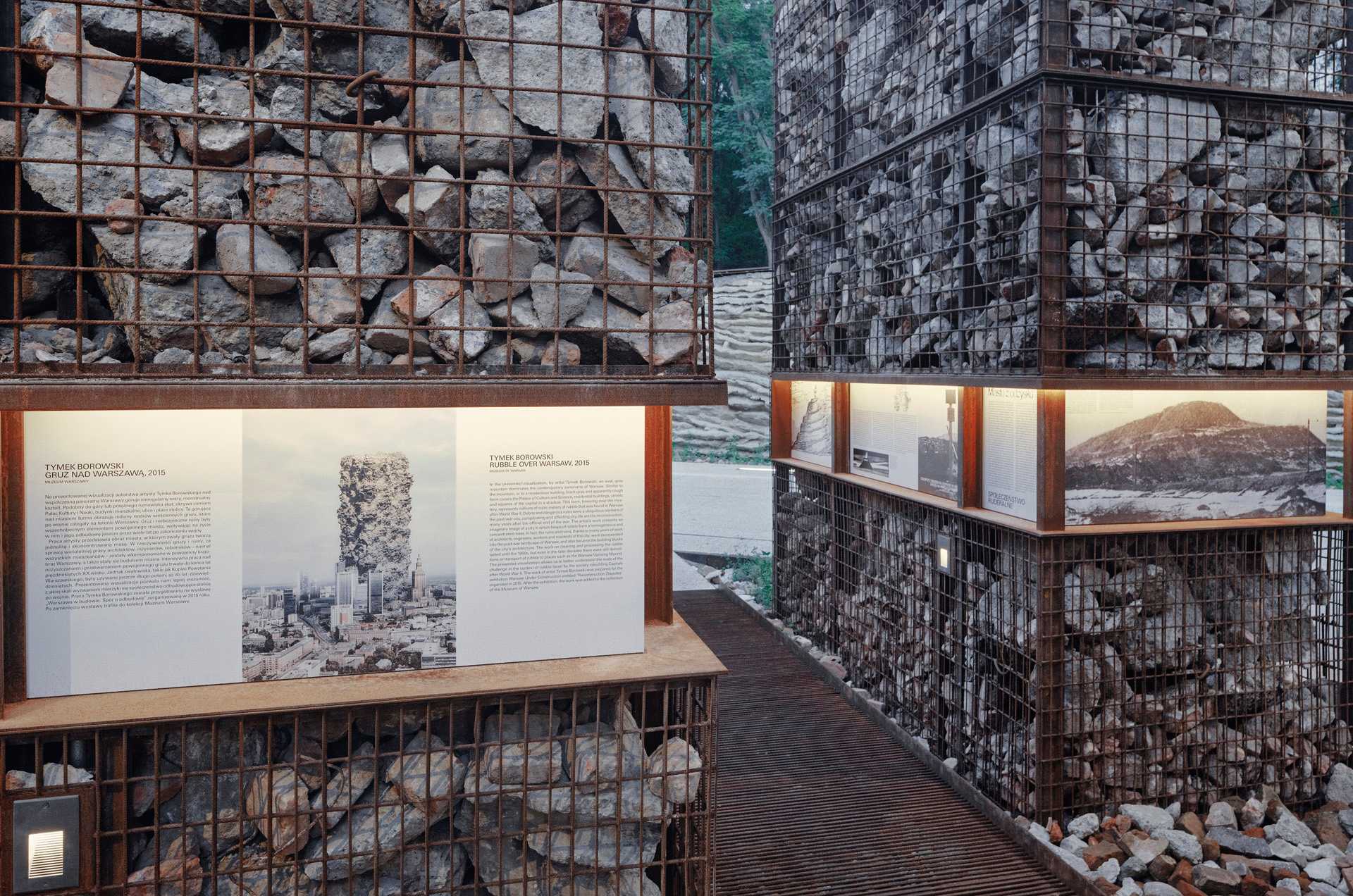

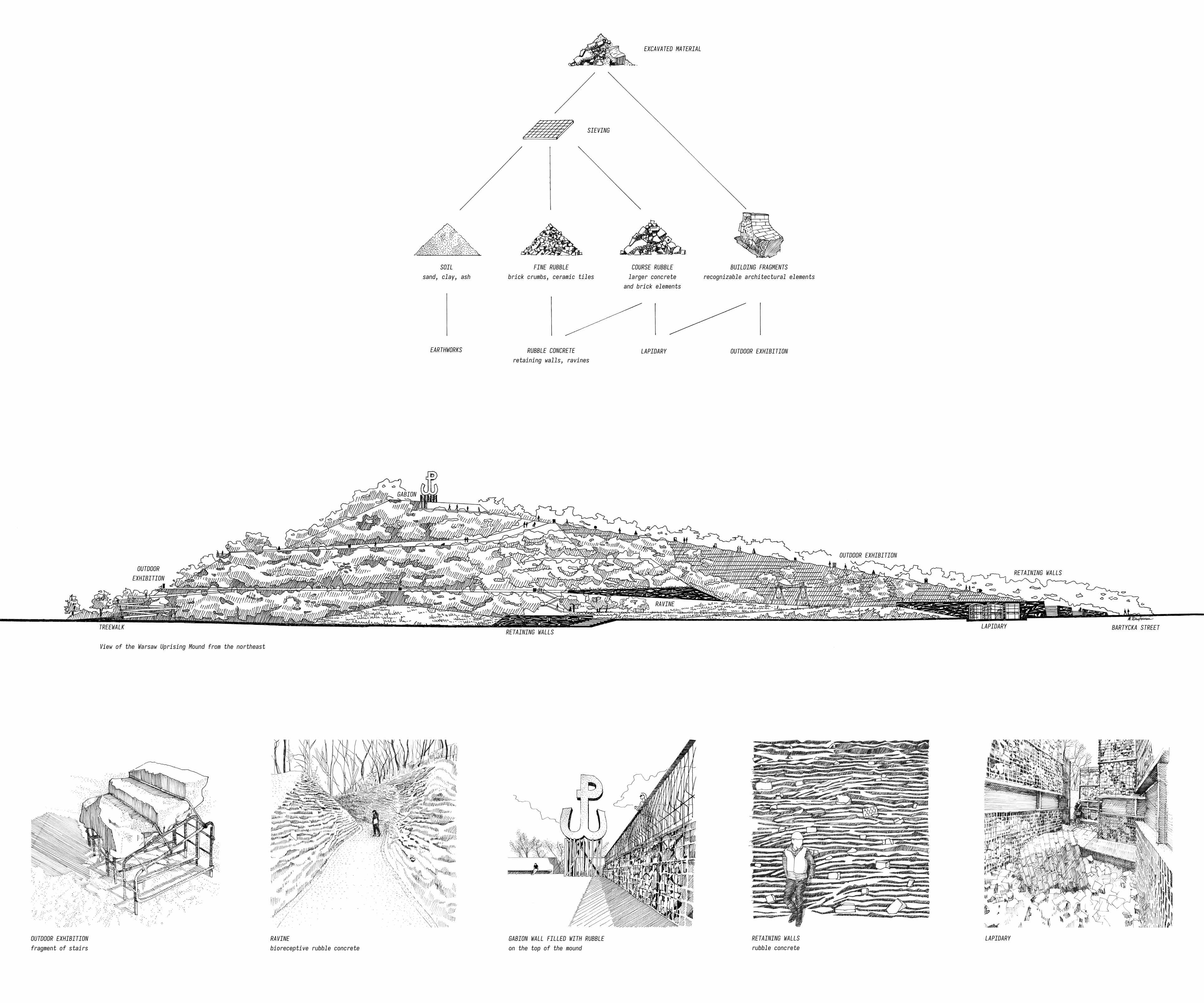

Over 20,000 m³ of WWII rubble and soil were repurposed on-site, reducing waste and reinforcing Warsaw’s circular economy legacy. The project also innovatively reused wartime debris. Retaining walls, gabions, and the exhibition are constructed with extensive use of rubble, echoing Warsaw’s post-war reconstruction. This approach minimized the carbon footprint while preserving historical identity. Debris and invasive ruderal vegetation were reframed as historical and ecological assets, demonstrating how urban wastelands can become sustainable, biodiverse spaces.

A key focus was ecological restoration. Water and soil management stabilized the site. Hundreds of meters of low fascine fences were installed to combat erosion, retain organic matter, and foster soil formation. A multi-point water retention system turned runoff into a resource, protecting hydrology and reducing degradation. Certain areas were left inaccessible to protect wildlife. Artificial lighting was reduced to support nocturnal species.

Native species were introduced to boost biodiversity, while pioneer vegetation that naturally colonized the site was integrated into the restoration. The landscape was designed to evolve naturally, maintaining its wild, self-sustaining character with plantings that blend seamlessly into existing vegetation. Phytosociological studies guided plant selection, ensuring ecological compatibility. More than 70,000 plants were planted. In the future, planted young forest saplings will replace invasive ruderal trees, allowing natural selection to shape the woodland ecosystem.

Over 20,000 m³ of WWII rubble and soil were repurposed on-site, reducing waste and reinforcing Warsaw’s circular economy legacy. The project also innovatively reused wartime debris. Retaining walls, gabions, and the exhibition are constructed with extensive use of rubble, echoing Warsaw’s post-war reconstruction. This approach minimized the carbon footprint while preserving historical identity. Debris and invasive ruderal vegetation were reframed as historical and ecological assets, demonstrating how urban wastelands can become sustainable, biodiverse spaces.

The Warsaw Uprising Mound Park merges the aesthetics of "new wildness" and "recycling" to create an inclusive, immersive landscape that honours the site's history. These two aesthetics correspond to distinct areas of the park: the recycling aesthetic corresponds to the commemorative zone, associated with the memory of the Warsaw Uprising, while the aesthetic of new wildness characterises the recreational areas.

The aesthetic of new wildness shifts the design paradigm from rigid, ornamental landscaping to one that values natural processes. In the project, we sought to preserve the charm of ruderal vegetation not found outside brownfield sites. Rather than transform or control this natural character, we have emphasised its authenticity and value. Spontaneous vegetation blends with unmanicured meadows, blurred edges, and decaying logs, creating a "fourth nature" environment that feels organic and ever-changing. This wild aesthetic is not just about appearance but about ecological function.

Complementing the wild aesthetic is the recycling aesthetic expressed through integrating wartime debris and rubble concrete in the landscape. The rubble canyons, gabions, and pedestals with pieces of demolished buildings reveal fragments of the past, grounding the site in historical authenticity. The park's design integrates wartime debris as a central aesthetic and cultural element, creating a tangible link to Warsaw's history.

The park enhances the quality of experience through diverse recreational opportunities. A natural playground with slope-embedded slides offers adventure for children, while wildflower meadows and shaded picnic areas encourage relaxation and social interaction. Elevated walkways and panoramic viewpoints create quiet contemplation, offering new perspectives on the surrounding landscape. Landscape management strategies have been implemented to give human users a sense of security, comfort and belonging.

The aesthetic of new wildness shifts the design paradigm from rigid, ornamental landscaping to one that values natural processes. In the project, we sought to preserve the charm of ruderal vegetation not found outside brownfield sites. Rather than transform or control this natural character, we have emphasised its authenticity and value. Spontaneous vegetation blends with unmanicured meadows, blurred edges, and decaying logs, creating a "fourth nature" environment that feels organic and ever-changing. This wild aesthetic is not just about appearance but about ecological function.

Complementing the wild aesthetic is the recycling aesthetic expressed through integrating wartime debris and rubble concrete in the landscape. The rubble canyons, gabions, and pedestals with pieces of demolished buildings reveal fragments of the past, grounding the site in historical authenticity. The park's design integrates wartime debris as a central aesthetic and cultural element, creating a tangible link to Warsaw's history.

The park enhances the quality of experience through diverse recreational opportunities. A natural playground with slope-embedded slides offers adventure for children, while wildflower meadows and shaded picnic areas encourage relaxation and social interaction. Elevated walkways and panoramic viewpoints create quiet contemplation, offering new perspectives on the surrounding landscape. Landscape management strategies have been implemented to give human users a sense of security, comfort and belonging.

The project ensures inclusivity through its informal aesthetics, elimination of physical barriers and community engagement.

Rather than adopting an exclusionary, elitist visual language, the park embraces the "unpolished" beauty of ruderal landscapes and recycling. This aesthetics of regeneration allows the space to be perceived as accessible and inclusive, with a "low entry threshold" where everyone can feel at ease. The careful zoning allowed for a conflict-free combination of the functions of a historical monument and everyday recreation. Free entry, multilingual signage, facilities for the visually impaired, and inclusive recreational zones—such as sensory-rich natural playgrounds, shaded rest areas, and picnic spaces—ensure the park is accessible to people of all backgrounds.

Given the mound's significant elevation changes—rising 40 meters from its base to the summit—accessibility interventions were essential to transform the historically inaccessible terrain into a welcoming, navigable space. Ramps, gentle slopes, and elevated walkways allow wheelchair users and families with strollers to traverse the park's steep landscape, while an accessible pathway winding through the trees creates seamless connections to nearby residential areas. These significant engineering interventions have become the park's attractions on their own. The park also serves as a functional transit corridor, providing pedestrians a direct route between new housing developments and the older parts of the city. On the other hand, leaving selected areas unlit and inaccessible to humans, it recognizes fauna, flora, and fungi as spatial agents.

The residents actively participated in the project through BioBlitz research, public consultations, and collaborative planting events. This participatory approach fostered a sense of ownership, resulting in increased social control. To date, we have not recorded any acts of vandalism.

Rather than adopting an exclusionary, elitist visual language, the park embraces the "unpolished" beauty of ruderal landscapes and recycling. This aesthetics of regeneration allows the space to be perceived as accessible and inclusive, with a "low entry threshold" where everyone can feel at ease. The careful zoning allowed for a conflict-free combination of the functions of a historical monument and everyday recreation. Free entry, multilingual signage, facilities for the visually impaired, and inclusive recreational zones—such as sensory-rich natural playgrounds, shaded rest areas, and picnic spaces—ensure the park is accessible to people of all backgrounds.

Given the mound's significant elevation changes—rising 40 meters from its base to the summit—accessibility interventions were essential to transform the historically inaccessible terrain into a welcoming, navigable space. Ramps, gentle slopes, and elevated walkways allow wheelchair users and families with strollers to traverse the park's steep landscape, while an accessible pathway winding through the trees creates seamless connections to nearby residential areas. These significant engineering interventions have become the park's attractions on their own. The park also serves as a functional transit corridor, providing pedestrians a direct route between new housing developments and the older parts of the city. On the other hand, leaving selected areas unlit and inaccessible to humans, it recognizes fauna, flora, and fungi as spatial agents.

The residents actively participated in the project through BioBlitz research, public consultations, and collaborative planting events. This participatory approach fostered a sense of ownership, resulting in increased social control. To date, we have not recorded any acts of vandalism.

The grassroots civic initiative lies at the core of this project. In 1994, veterans erected a monument on the former landfill, naming it the Warsaw Uprising Mound and creating a site for annual commemorations. Despite this, the area remained largely inaccessible and unsafe, leading veterans to advocate for the creation of a public park.

In 2019, an architectural competition for the park’s design was preceded by public consultations and an ecological inventory (BioBlitz). Residents and local organizations emphasized the need to improve safety, introduce recreational spaces like resting spots and picnic areas, and preserve the area’s green, open character while honoring its historical significance. The BioBlitz, led by volunteers, documented local biodiversity and shaped a planting strategy that balanced pioneer and native species, preserving unique habitats such as summit marsh vegetation.

The knowledge gained during consultations and the inventory informed the 13 competition proposals. A jury, including city officials and community representatives, selected the winning project, which was later presented and discussed publicly at the cultural center Dorożkarnia. During construction, residents were kept informed about key changes through walks with dendrologists, ensuring transparency and fostering dialogue. The opening of the park was preceded by a community planting of a pocket forest using the method of Professor Miyawaki by 100 volunteers under the supervision of municipal gardeners. The event was financed by an association of developers operating in the vicinity.

Following the park’s opening, in response to high community demand, the designers organized over 30 guided tours for nearly 500 residents and professionals. The park has become a vibrant space, meeting local needs while celebrating its historical significance. It now serves as both a living memorial and a public refuge, demonstrating the impact of grassroots involvement in urban transformation.

In 2019, an architectural competition for the park’s design was preceded by public consultations and an ecological inventory (BioBlitz). Residents and local organizations emphasized the need to improve safety, introduce recreational spaces like resting spots and picnic areas, and preserve the area’s green, open character while honoring its historical significance. The BioBlitz, led by volunteers, documented local biodiversity and shaped a planting strategy that balanced pioneer and native species, preserving unique habitats such as summit marsh vegetation.

The knowledge gained during consultations and the inventory informed the 13 competition proposals. A jury, including city officials and community representatives, selected the winning project, which was later presented and discussed publicly at the cultural center Dorożkarnia. During construction, residents were kept informed about key changes through walks with dendrologists, ensuring transparency and fostering dialogue. The opening of the park was preceded by a community planting of a pocket forest using the method of Professor Miyawaki by 100 volunteers under the supervision of municipal gardeners. The event was financed by an association of developers operating in the vicinity.

Following the park’s opening, in response to high community demand, the designers organized over 30 guided tours for nearly 500 residents and professionals. The park has become a vibrant space, meeting local needs while celebrating its historical significance. It now serves as both a living memorial and a public refuge, demonstrating the impact of grassroots involvement in urban transformation.

The project ensured a multi-level, cross-sectoral engagement of stakeholders at European, national, regional, and local levels, fostering synergy between policy objectives and on-the-ground implementation. It was developed under Action 2.5, "Enhancing Urban Environmental Quality”. EU strategic priorities guided the project’s focus on biodiversity enhancement and strengthening the resilience of existing vegetation to climate change impacts.

Key national level stakeholders included representatives of the Warsaw Uprising Insurgents Association and the World Association of Home Army Soldiers. Given that the memorial site originated as a bottom-up initiative led by veterans, their substantive input was pivotal in shaping the site’s symbolic and commemorative functions. Comprehensive stakeholder engagement included in-depth interviews and coordination with all entities responsible for the annual Warsaw Uprising commemoration events. Additionally, historical consultations with the Warsaw Uprising Museum (national level) and the Museum of Warsaw (regional level) contributed to the conceptualization of the site's historical narrative and the development of a permanent educational exhibition on the destruction and reconstruction of Warsaw.

At the local level, participatory planning mechanisms ensured alignment with community needs. Inclusive consultations incorporated public debates, on-site engagement points, and thematic historical and ecological walks. The outcome was a comprehensive needs assessment and a set of design guidelines. The participatory process involved residents, NGOs, foundations, housing cooperatives, and cultural institutions, facilitated by the University of Warsaw’s Center for Social Challenges. Design guidelines were elaborated by the Skwer Sportów Miejskich Foundation. Ensuring long-term results in, local stakeholders were actively involved in implementing the project, including the planting of a pocket forest.

Key national level stakeholders included representatives of the Warsaw Uprising Insurgents Association and the World Association of Home Army Soldiers. Given that the memorial site originated as a bottom-up initiative led by veterans, their substantive input was pivotal in shaping the site’s symbolic and commemorative functions. Comprehensive stakeholder engagement included in-depth interviews and coordination with all entities responsible for the annual Warsaw Uprising commemoration events. Additionally, historical consultations with the Warsaw Uprising Museum (national level) and the Museum of Warsaw (regional level) contributed to the conceptualization of the site's historical narrative and the development of a permanent educational exhibition on the destruction and reconstruction of Warsaw.

At the local level, participatory planning mechanisms ensured alignment with community needs. Inclusive consultations incorporated public debates, on-site engagement points, and thematic historical and ecological walks. The outcome was a comprehensive needs assessment and a set of design guidelines. The participatory process involved residents, NGOs, foundations, housing cooperatives, and cultural institutions, facilitated by the University of Warsaw’s Center for Social Challenges. Design guidelines were elaborated by the Skwer Sportów Miejskich Foundation. Ensuring long-term results in, local stakeholders were actively involved in implementing the project, including the planting of a pocket forest.

The project was developed through collaboration between specialists in engineering, social and natural sciences.

Sociologists engaged local communities in consultations through workshops, surveys, and discussions, gathering insights into residents' expectations. These resulted in the Catalogue of Needs, which shaped competition guidelines and ensured public involvement in the design process.

Historical research helped identify and understand local resources for construction. Historical botanical studies of post-WWII vegetation informed the development of contemporary seed mixtures for the rubble substrate. Engineers built on historical recycling techniques from the 1940s to create modern bioreceptive rubble concrete inoculated with moss spores.

Phytosociologists guided native plant selection and erosion control, ensuring compatibility with ruderal ecosystems. Their perspective reconstructed the site's "natural history," predicting its ecological future and accelerating the process through targeted plantings. This significantly influenced the park's aesthetic. Experts such as ornithologists, botanists, chiropterologists, theriologists, lichenologists, and mycologists contributed their BioBlitz expertise, shaping a biodiverse and self-sustaining environment.

Geologists, civil engineers, and concrete technologists developed slope stabilization techniques using recycled materials. Skilled craftsmen constructed retaining walls, layering rubble concrete to ensure structural integrity and a visually compelling texture that integrates with natural erosion patterns.

The close collaboration between these disciplines allowed for developing a cohesive, site-specific narrative and design. The resulting knowledge was made accessible to the public through bilingual educational boards on natural and historical topics, designed by professional educators and graphic designers to enhance clarity, engagement, and unique aesthetic tailored to the site's character.

Sociologists engaged local communities in consultations through workshops, surveys, and discussions, gathering insights into residents' expectations. These resulted in the Catalogue of Needs, which shaped competition guidelines and ensured public involvement in the design process.

Historical research helped identify and understand local resources for construction. Historical botanical studies of post-WWII vegetation informed the development of contemporary seed mixtures for the rubble substrate. Engineers built on historical recycling techniques from the 1940s to create modern bioreceptive rubble concrete inoculated with moss spores.

Phytosociologists guided native plant selection and erosion control, ensuring compatibility with ruderal ecosystems. Their perspective reconstructed the site's "natural history," predicting its ecological future and accelerating the process through targeted plantings. This significantly influenced the park's aesthetic. Experts such as ornithologists, botanists, chiropterologists, theriologists, lichenologists, and mycologists contributed their BioBlitz expertise, shaping a biodiverse and self-sustaining environment.

Geologists, civil engineers, and concrete technologists developed slope stabilization techniques using recycled materials. Skilled craftsmen constructed retaining walls, layering rubble concrete to ensure structural integrity and a visually compelling texture that integrates with natural erosion patterns.

The close collaboration between these disciplines allowed for developing a cohesive, site-specific narrative and design. The resulting knowledge was made accessible to the public through bilingual educational boards on natural and historical topics, designed by professional educators and graphic designers to enhance clarity, engagement, and unique aesthetic tailored to the site's character.

The project adopted a strategy of complete reuse of materials excavated during construction. This material management approach enabled the full utilization of all excavated material as a resource. The rubble was repurposed in its raw form as drystack walls, gabion fill, and as a component of rubble concrete—an innovative, bioreceptive urban rock. Its composition and application make it bioreceptive, meaning it provides a potential habitat for pioneer plant species. The final phase of work involved the deliberate introduction of mosses. Rubble concrete was used in the retaining walls, designed to resemble the geological cross-section of the mound. These walls are the result of collaboration between designers and experts but also serve as an expression of the craftsmanship of the workers who built them. It was they who selected and embedded fragments of old Warsaw—building elements, bricks and tiles—into the structure.

The project applies forest management strategies to the design of green public spaces—an entirely novel approach. Instead of an aesthetics-driven methodology, it adopts a process-oriented strategy, dynamically responding to environmental changes such as erosion, spontaneous vegetation growth, and ecosystem shifts. Biodiversity is enhanced not only by introducing new species but also through genetic diversity: planting genetically varied forest seedlings from local nurseries and native perennials adapted to site-specific soil conditions. Also an innovative area-based planting method was developed, allowing for the replication of complex natural succession processes, even by unskilled laborers.

By merging ecological resilience with cultural memory, the project exemplifies regenerative urbanism, prioritizing adaptive, site-specific processes over static, ornamental solutions. Through the artistic reinterpretation of waste and the exposure of the site's layered history, it redefines urban greening, transforming ruins into a dynamic cultural landscap.

The project applies forest management strategies to the design of green public spaces—an entirely novel approach. Instead of an aesthetics-driven methodology, it adopts a process-oriented strategy, dynamically responding to environmental changes such as erosion, spontaneous vegetation growth, and ecosystem shifts. Biodiversity is enhanced not only by introducing new species but also through genetic diversity: planting genetically varied forest seedlings from local nurseries and native perennials adapted to site-specific soil conditions. Also an innovative area-based planting method was developed, allowing for the replication of complex natural succession processes, even by unskilled laborers.

By merging ecological resilience with cultural memory, the project exemplifies regenerative urbanism, prioritizing adaptive, site-specific processes over static, ornamental solutions. Through the artistic reinterpretation of waste and the exposure of the site's layered history, it redefines urban greening, transforming ruins into a dynamic cultural landscap.

The park design is based on an interdisciplinary approach. Key aspects are:

1. Public consultations, BioBlitz and local resource assessment

During the analysis phase, a BioBlitz study and public consultations engaged residents in documenting biodiversity and shaping the project’s vision. A local resource assessment then identified 13,000 m³ of historical debris suitable for reuse. This material was repurposed into gabions, pathway foundations, and rubble concrete, achieving sustainability through a circular economy.

2. Ecosystem Approach – Fourth Nature focusing on the process not visual aspects

The project applies the concept of Fourth Nature, focusing on regenerating degraded land through minimal intervention in natural processes. Spontaneous plant succession was encouraged, allowing ruderal pioneer species to coexist with introduced native species. A hybrid Novel Ecosystem was developed using the phytosociological reference ecosystems method. New plantings were mixed to mimic natural randomness.

3. Landscape Management Through Non-Intervention

A key principle was limiting excessive control and maintenance. Invasive species were not removed, as they have been identified as a natural stage of succession. No classic soil cultivation was carried out. Erosion was regulated by biotechnical stabilization methods, supporting natural soil-forming processes.

4. Integration of historical knowledge

The project draws from Warsaw’s post-WWII reconstruction, where rubble was repurposed to rebuild the city. In-depth research on historical practices and technologies informed the development of a contemporary material that complies with Eurocodes.

The methodology combines scientific principles with minimal intervention and heritage preservation. Rather than imposing rigid solutions, it establishes a framework for landscape evolution in a process-driven design. Success is measured by the ecosystem’s self-regulation rather than aesthetic perfection.

1. Public consultations, BioBlitz and local resource assessment

During the analysis phase, a BioBlitz study and public consultations engaged residents in documenting biodiversity and shaping the project’s vision. A local resource assessment then identified 13,000 m³ of historical debris suitable for reuse. This material was repurposed into gabions, pathway foundations, and rubble concrete, achieving sustainability through a circular economy.

2. Ecosystem Approach – Fourth Nature focusing on the process not visual aspects

The project applies the concept of Fourth Nature, focusing on regenerating degraded land through minimal intervention in natural processes. Spontaneous plant succession was encouraged, allowing ruderal pioneer species to coexist with introduced native species. A hybrid Novel Ecosystem was developed using the phytosociological reference ecosystems method. New plantings were mixed to mimic natural randomness.

3. Landscape Management Through Non-Intervention

A key principle was limiting excessive control and maintenance. Invasive species were not removed, as they have been identified as a natural stage of succession. No classic soil cultivation was carried out. Erosion was regulated by biotechnical stabilization methods, supporting natural soil-forming processes.

4. Integration of historical knowledge

The project draws from Warsaw’s post-WWII reconstruction, where rubble was repurposed to rebuild the city. In-depth research on historical practices and technologies informed the development of a contemporary material that complies with Eurocodes.

The methodology combines scientific principles with minimal intervention and heritage preservation. Rather than imposing rigid solutions, it establishes a framework for landscape evolution in a process-driven design. Success is measured by the ecosystem’s self-regulation rather than aesthetic perfection.

The project's approach could be replicable in post-industrial and post-conflict areas facing ecological degradation and fractured memory. A combination of 'soft' social actions and low-tech infrastructure interventions offers a cost-effective, adaptable model. Key transferable elements include:

1. Community Engagement

Active resident participation ensured long-term social sustainability, shaping both the park's vision and implementation (effective programming, inclusivity, and community ownership). Simple, traditional techniques required no specialized skills, allowing even children to participate under expert guidance. This approach minimized vandalism and strengthened local stewardship.

2. Rubble Reuse

WWII rubble was repurposed into infrastructure, reducing waste while preserving cultural heritage. "Warsaw urbanite"—a rubble-based concrete—revives circular economy principles. Crushed bricks and fragments became park structures, symbolizing resilience. This strategy, adaptable to other cities, transforms debris into both functional elements and memorials. A simple mix of spores and organic medium enables moss growth on its bioreceptive surfaces.

3. Ecological Restoration

Applying Fourth Nature principles, the project balanced spontaneous rewilding with targeted interventions. Pioneer species, even invasives, aided soil detoxification; fascine fences stabilized slopes; native meadow seeds restored habitats. Deadwood was repurposed for mulch, erosion control, insect habitats, and closing material cycles. Ruderal forests were left to transition naturally into native woodlands, creating self-sustaining ecosystems.

Replication requires site-specific adaptation—drought-resistant flora, urban agriculture, or cultural narratives. Low-tech, community-driven strategies and partnerships between municipalities, NGOs, and professionals can align sustainability goals with local needs.

1. Community Engagement

Active resident participation ensured long-term social sustainability, shaping both the park's vision and implementation (effective programming, inclusivity, and community ownership). Simple, traditional techniques required no specialized skills, allowing even children to participate under expert guidance. This approach minimized vandalism and strengthened local stewardship.

2. Rubble Reuse

WWII rubble was repurposed into infrastructure, reducing waste while preserving cultural heritage. "Warsaw urbanite"—a rubble-based concrete—revives circular economy principles. Crushed bricks and fragments became park structures, symbolizing resilience. This strategy, adaptable to other cities, transforms debris into both functional elements and memorials. A simple mix of spores and organic medium enables moss growth on its bioreceptive surfaces.

3. Ecological Restoration

Applying Fourth Nature principles, the project balanced spontaneous rewilding with targeted interventions. Pioneer species, even invasives, aided soil detoxification; fascine fences stabilized slopes; native meadow seeds restored habitats. Deadwood was repurposed for mulch, erosion control, insect habitats, and closing material cycles. Ruderal forests were left to transition naturally into native woodlands, creating self-sustaining ecosystems.

Replication requires site-specific adaptation—drought-resistant flora, urban agriculture, or cultural narratives. Low-tech, community-driven strategies and partnerships between municipalities, NGOs, and professionals can align sustainability goals with local needs.

Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation.

The project made full use of excavated rubble, reducing landfill waste and carbon gas emissions - a hyper-local response to the global crisis of resource overconsumption. The integration of spontaneous vegetation and native meadows cools urban microclimates, countering heat islands, while water-retention systems tackle drought risks exacerbated by climate extremes. These strategies exemplify how circular material practices and nature-based solutions can scale to cities worldwide.

Soil erosion

The project uses innovative solutions but also draws on traditional bioengineering techniques (e.g., fascine fences, vegetated drains, green retaining walls, terracing of slopes with infiltration zones), which are intended to counteract anthropogenic soil erosion, the accumulation of organic matter and the conscious management of rainwater.

Biodiversity Loss

The park combats ecosystem degradation by embracing "Fourth Nature"—allowing degraded urban sites to regenerate through natural processes. Locally sourced genetically diverse plants and native tree saplings from regional nurseries ensured better adaptation to local soil and climate conditions. Deadwood recycling for insect habitats and reintroducing meadows revive ecological networks and native ecosystems.

Social Inequality and Exclusion.

The project transforms neglected spaces into inclusive hubs through community co-design. Accessible pathways, natural playgrounds, and participatory workshops ensure marginalised groups—from elderly residents to children with disabilities—can shape and access the park. By reframing rubble as shared cultural heritage, the park also heals social fractures caused by conflict or displacement, offering a blueprint for reconciling collective memory with equitable urban development. By creating a local identity based on the city's history and its inhabitants' involvement, the project counters globalisation and alienation.

The project made full use of excavated rubble, reducing landfill waste and carbon gas emissions - a hyper-local response to the global crisis of resource overconsumption. The integration of spontaneous vegetation and native meadows cools urban microclimates, countering heat islands, while water-retention systems tackle drought risks exacerbated by climate extremes. These strategies exemplify how circular material practices and nature-based solutions can scale to cities worldwide.

Soil erosion

The project uses innovative solutions but also draws on traditional bioengineering techniques (e.g., fascine fences, vegetated drains, green retaining walls, terracing of slopes with infiltration zones), which are intended to counteract anthropogenic soil erosion, the accumulation of organic matter and the conscious management of rainwater.

Biodiversity Loss

The park combats ecosystem degradation by embracing "Fourth Nature"—allowing degraded urban sites to regenerate through natural processes. Locally sourced genetically diverse plants and native tree saplings from regional nurseries ensured better adaptation to local soil and climate conditions. Deadwood recycling for insect habitats and reintroducing meadows revive ecological networks and native ecosystems.

Social Inequality and Exclusion.

The project transforms neglected spaces into inclusive hubs through community co-design. Accessible pathways, natural playgrounds, and participatory workshops ensure marginalised groups—from elderly residents to children with disabilities—can shape and access the park. By reframing rubble as shared cultural heritage, the park also heals social fractures caused by conflict or displacement, offering a blueprint for reconciling collective memory with equitable urban development. By creating a local identity based on the city's history and its inhabitants' involvement, the project counters globalisation and alienation.

The park on the Warsaw Uprising Mound offers high ecosystem services and requires low maintenance costs. An area that was previously treated as a wasteland is now embraced as a welcoming space that allows visitors to experience being part of nature. The establishment of this park has brought the concept of fourth nature into public discourse in Poland fostering a change of perspective towards nature. The insights gained from this project have contributed to the development of new urban standards that the city is systematically implementing.

By improving accessibility the park has become a local green hub that integrates both new and longtime residents of the neighborhood. It serves as a connector between shared spaces and communal areas. The playgrounds and recreational spaces designed for different generations and user groups have significantly increased foot traffic, making the park not only a venue that meets local needs but also a destination for the entire city and tourists alike.

The park is the result of a grassroots initiative of the Warsaw Uprising Combatants and has established a respectful setting for local anniversary celebrations, enhancing their significance in the long term.

The park restores the heritage of post-war reconstruction as a collective effort. Indirectly the design of the mound has influenced the exhibition “Rubbleuprise” in the Historical Museum of Warsaw and has also introduced circular economy solutions as embedded in local tradition (rubble concrete).

The park serves as a civic hub, hosting educational programs, cultural events, commemoration, and anti-war protests, reinforcing its role as a place of memory and activism.

Indirectly, the project has become a global source of inspiration, demonstrating how post-trauma landscapes can be transformed into regenerative spaces that balance human needs with planetary health and principles of the circular economy.

By improving accessibility the park has become a local green hub that integrates both new and longtime residents of the neighborhood. It serves as a connector between shared spaces and communal areas. The playgrounds and recreational spaces designed for different generations and user groups have significantly increased foot traffic, making the park not only a venue that meets local needs but also a destination for the entire city and tourists alike.

The park is the result of a grassroots initiative of the Warsaw Uprising Combatants and has established a respectful setting for local anniversary celebrations, enhancing their significance in the long term.

The park restores the heritage of post-war reconstruction as a collective effort. Indirectly the design of the mound has influenced the exhibition “Rubbleuprise” in the Historical Museum of Warsaw and has also introduced circular economy solutions as embedded in local tradition (rubble concrete).

The park serves as a civic hub, hosting educational programs, cultural events, commemoration, and anti-war protests, reinforcing its role as a place of memory and activism.

Indirectly, the project has become a global source of inspiration, demonstrating how post-trauma landscapes can be transformed into regenerative spaces that balance human needs with planetary health and principles of the circular economy.