Reconnecting with nature

Vielwald

When design students grow a circular forest for their neighbourhood in Cologne.

Vielwald (polyforest in German) embodies the idea of transforming a generic patch of grass into a lush public space where plants are grown by locals, in collaboration with the design students, for uses such as food, remedies, materials and dyes. Vielwald is becoming a rich pedagogic experience for local neighbours and students as they design the space together and transform the harvest into new materials and food that can be cooked together.

Germany

Local

Köln

Mainly urban

It refers to a physical transformation of the built environment (hard investment)

Prototype level

No

No

As a representative of an organisation

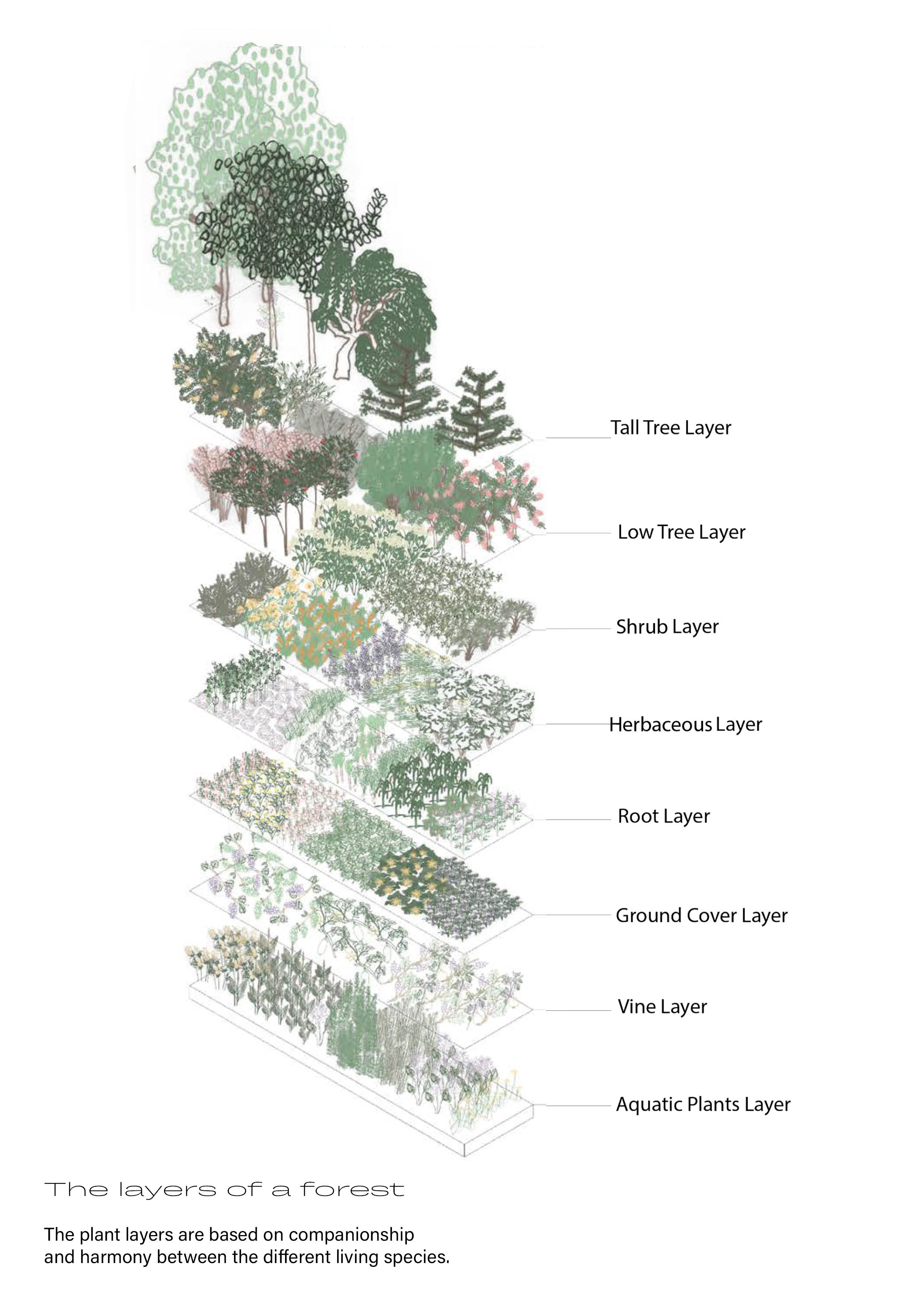

Urban forest gardens have incredible potential. As they replicate the natural ecosystem of native forests by creating multi-layered, resilient and very productive spaces, a forest garden showcases a wide variety of plants for citizens and animals to enjoy.

In 2019, students of KISD (Köln International School of Design), Anna Luz Pueyo and Clara Schmeinck discovered this system on a research trip to Taiwan, observing what it could offer to the community of the city of Hsinchu.

Once back in Cologne, they researched local plants adapted for the German climate, and looked for a space to grow a forest garden, in collaboration with the design school and the city’s nutrition council.

After a long search for the right spot, three green spaces were finally proposed by the department of green spaces in Cologne to grow the forest garden. Since September 2023, a working group is officially part of the school curriculum and fifteen motivated students come together every week to make the project come to life.

Vielwald (polyforest in German) embodies the idea of transforming a generic patch of grass into a lush public space where plants are grown by locals, in collaboration with the design students, for uses such as food, remedies, materials and dyes. Vielwald is becoming a rich pedagogic experience for local neighbours and students as they design the space together and transform the harvest into new materials and food that can be cooked together.

The forest garden is allowing neighbours and students to connect to nature by actively working with the soil and experiencing the productivity and beauty of the forest in their direct surroundings. Together, they contribute to better air, soil and biodiversity. A new porosity between the school and the public space comes to life, in direct reference to the way the German Bauhaus used to honour its context and embrace multiple disciplines.

In 2019, students of KISD (Köln International School of Design), Anna Luz Pueyo and Clara Schmeinck discovered this system on a research trip to Taiwan, observing what it could offer to the community of the city of Hsinchu.

Once back in Cologne, they researched local plants adapted for the German climate, and looked for a space to grow a forest garden, in collaboration with the design school and the city’s nutrition council.

After a long search for the right spot, three green spaces were finally proposed by the department of green spaces in Cologne to grow the forest garden. Since September 2023, a working group is officially part of the school curriculum and fifteen motivated students come together every week to make the project come to life.

Vielwald (polyforest in German) embodies the idea of transforming a generic patch of grass into a lush public space where plants are grown by locals, in collaboration with the design students, for uses such as food, remedies, materials and dyes. Vielwald is becoming a rich pedagogic experience for local neighbours and students as they design the space together and transform the harvest into new materials and food that can be cooked together.

The forest garden is allowing neighbours and students to connect to nature by actively working with the soil and experiencing the productivity and beauty of the forest in their direct surroundings. Together, they contribute to better air, soil and biodiversity. A new porosity between the school and the public space comes to life, in direct reference to the way the German Bauhaus used to honour its context and embrace multiple disciplines.

Regenerative Placemaking

Social Fermentation

Activation of Public Space

Collaborative Pedagogy

Lost uses of local plants

This initiative has both local and global effects on the environment, responding to the challenges of urbanisation today.

1. Letting native species return.

In a forest garden, plants on all levels cooperate : trees, shrubs, bushes, herbaceous plants, ground covers, roots, lianas... They work in symbiosis, with no other input than local compost. Compared to a traditional urban park, the biodiversity per square metre increases because the vegetation occupies the space in 3D. This favours the arrival of pollinating insects such as solitary bees and butterflies. For each layer, we identified a dozen varieties that could collaborate, even in a small area like ours. The food forests of Hsinchu, our case study, showed that biodiversity was increased by 2000% compared to the neighbouring park!

2. Preventing soil erosion thanks to the network of roots underground.

A food forest is like a primitive forest, except that all species are edible or usable as materials, to then be returned to the soil after use. The practice of pruning branches and using compost to create a rich humus helps regenerate a nutritious soil. Earthworms, bacteria, protozoa, springtails or other microorganisms make the soil alive.

3. Contributing to water management in the city.

Water drainage is managed better, as it can be absorbed easily by the vegetation and the porous soil. Furthermore, the tree canopy absorbs CO2 and creates islands of coolness, a direct solution to fight climate change and to regulate unstable weather patterns.

4. Fostering circular design practices.

Vielwald embodies a design practice with circularity at its core, as all products designed by students and locals are thought to be returned to the soil after use. The proximity of the circular garden to the school labs will put this micro production chain to the test, rooting this mindset in the workshops’ culture and transmitting it to the local neighbours.

1. Letting native species return.

In a forest garden, plants on all levels cooperate : trees, shrubs, bushes, herbaceous plants, ground covers, roots, lianas... They work in symbiosis, with no other input than local compost. Compared to a traditional urban park, the biodiversity per square metre increases because the vegetation occupies the space in 3D. This favours the arrival of pollinating insects such as solitary bees and butterflies. For each layer, we identified a dozen varieties that could collaborate, even in a small area like ours. The food forests of Hsinchu, our case study, showed that biodiversity was increased by 2000% compared to the neighbouring park!

2. Preventing soil erosion thanks to the network of roots underground.

A food forest is like a primitive forest, except that all species are edible or usable as materials, to then be returned to the soil after use. The practice of pruning branches and using compost to create a rich humus helps regenerate a nutritious soil. Earthworms, bacteria, protozoa, springtails or other microorganisms make the soil alive.

3. Contributing to water management in the city.

Water drainage is managed better, as it can be absorbed easily by the vegetation and the porous soil. Furthermore, the tree canopy absorbs CO2 and creates islands of coolness, a direct solution to fight climate change and to regulate unstable weather patterns.

4. Fostering circular design practices.

Vielwald embodies a design practice with circularity at its core, as all products designed by students and locals are thought to be returned to the soil after use. The proximity of the circular garden to the school labs will put this micro production chain to the test, rooting this mindset in the workshops’ culture and transmitting it to the local neighbours.

1. A sensorial space

Most green spaces in cities are a combination of green spreads of cut-grass and a selection of trees that we walk through without much interaction. Recreating a forest environment gives citizens access to a lush, dense and colourful space, which has a direct impact on their quality of life. The colour palette of the combined species, the smell of soil and plants, the sounds of birds and insects, the textures of leaves, the taste of the fresh harvest: all five senses are stimulated.

2. Connecting to our roots

Reconnecting with local plants is a sensorial experience in itself, one of increasing value in a society where most citizens work behind screens. Spending time growing food and materials gets rewarded with the harvest, unlocking emotions of accomplishment, pride and engagement. Satisfaction will also come from the wonders of learning something new, rooting back to cultural connections to plants and trees and making a step towards self-sufficiency. Locals will connect differently with the products they use in daily life and understand their value.

3. Rediscovering local crafts

On a global level, the Vielwald makes way for local circuits of foods and materials. The project integrates the development of the circular material library (already in process), a shared database documenting uses of local plants. This work will be reinforced by unveiling a lost legacy of crafts and recipes such as basketry, paper making, natural dyes, pastry, fermentation or woodwork within design projects at KISD, making way for beautiful products.

4. Brightening up the neighbourhood

The Vielwald will also be a social space, where neighbours across generations can meet up and interact on various occasions programmed by the working group. This will genuinely impact the quality of life in the neighbourhood, and contribute to a feeling of safety and solidarity in the city.

Most green spaces in cities are a combination of green spreads of cut-grass and a selection of trees that we walk through without much interaction. Recreating a forest environment gives citizens access to a lush, dense and colourful space, which has a direct impact on their quality of life. The colour palette of the combined species, the smell of soil and plants, the sounds of birds and insects, the textures of leaves, the taste of the fresh harvest: all five senses are stimulated.

2. Connecting to our roots

Reconnecting with local plants is a sensorial experience in itself, one of increasing value in a society where most citizens work behind screens. Spending time growing food and materials gets rewarded with the harvest, unlocking emotions of accomplishment, pride and engagement. Satisfaction will also come from the wonders of learning something new, rooting back to cultural connections to plants and trees and making a step towards self-sufficiency. Locals will connect differently with the products they use in daily life and understand their value.

3. Rediscovering local crafts

On a global level, the Vielwald makes way for local circuits of foods and materials. The project integrates the development of the circular material library (already in process), a shared database documenting uses of local plants. This work will be reinforced by unveiling a lost legacy of crafts and recipes such as basketry, paper making, natural dyes, pastry, fermentation or woodwork within design projects at KISD, making way for beautiful products.

4. Brightening up the neighbourhood

The Vielwald will also be a social space, where neighbours across generations can meet up and interact on various occasions programmed by the working group. This will genuinely impact the quality of life in the neighbourhood, and contribute to a feeling of safety and solidarity in the city.

1. Co-designing with the users

The design school and the space of the Vielwald are both located in the Sudstadt, an area of Cologne populated by many generations, backgrounds and origins. During our field research, we observed that green spaces are already used as a social space: dog walking areas, playgrounds for kids or exercise spots for adults. Because the forest garden will be grown in this public space, the current users of the site are invited from the beginning to co-design the space with us, as part of the decision-making. For example, our value wheels are currently on site for users to decide on the types of plants they would like to grow.

2. Free produce

Generating food together with a local community that can be freely shared is a direct way to address food insecurity in cities. If the initiative spreads to other green spaces, it can create an alternative food system on a local scale. Retrieving food and other objects from the forest means that money typically spent in the supermarket can be saved. In the long run, we imagine that committing half a day to the food forest can replace half a day of the working week for some, enabling models such as the 4 day working week to rise.

3. Education for all

Activities of transformation of the harvest can get all publics involved with plant knowledge, giving way for integration opportunities, as a way to fight educational imbalance.

We see the Vielwald as a great opportunity to make space for all generations, through activities and plantation groups. Design principles of the forest itself will also have a role to play in inclusivity: the hügelkultur, a vernacular German principle, is a way to grow vegetables on a mound that is ergonomic for all heights of gardeners.

We envision a buddy system where groups of volunteers gather a mix of students and neighbours around the same activity, creating proximity across cultures and challenging the generation gap.

The design school and the space of the Vielwald are both located in the Sudstadt, an area of Cologne populated by many generations, backgrounds and origins. During our field research, we observed that green spaces are already used as a social space: dog walking areas, playgrounds for kids or exercise spots for adults. Because the forest garden will be grown in this public space, the current users of the site are invited from the beginning to co-design the space with us, as part of the decision-making. For example, our value wheels are currently on site for users to decide on the types of plants they would like to grow.

2. Free produce

Generating food together with a local community that can be freely shared is a direct way to address food insecurity in cities. If the initiative spreads to other green spaces, it can create an alternative food system on a local scale. Retrieving food and other objects from the forest means that money typically spent in the supermarket can be saved. In the long run, we imagine that committing half a day to the food forest can replace half a day of the working week for some, enabling models such as the 4 day working week to rise.

3. Education for all

Activities of transformation of the harvest can get all publics involved with plant knowledge, giving way for integration opportunities, as a way to fight educational imbalance.

We see the Vielwald as a great opportunity to make space for all generations, through activities and plantation groups. Design principles of the forest itself will also have a role to play in inclusivity: the hügelkultur, a vernacular German principle, is a way to grow vegetables on a mound that is ergonomic for all heights of gardeners.

We envision a buddy system where groups of volunteers gather a mix of students and neighbours around the same activity, creating proximity across cultures and challenging the generation gap.

1. Including all users

Some users of the space, such as dog walkers, have already been identified as stakeholders that should be considered in the design of the forest. The working group has conducted interviews to integrate their needs to the design process from the beginning, thinking of strategies to involve non-humans in the circular forest. Dedicating the dog walking area to tall trees or material production are current options that will allow the project to be sustainable due to common agreements.

2. The working group as a core

As the Vielwald is located close to the design school, the working group of students is the connecting element between the two spaces. Communicating across the neighbourhood and exploring ways for local neighbours to engage will be a first step, to then take care of the space and organise activities to eventually grow food and materials across the seasons. Families, shop owners, regular visitors of the space can take part and benefit from the initiative, through harvests but also through shared plant knowledge.

3. An activity-based system

The system of the Vielwald will work organically: a designated platform will be placed on site for visitors to sign up for the next events. People who contributed will also receive an invitation to the harvest days. The workshops of the design school will be used to build infrastructures and transform the products of the forest, with external actors joining within dedicated events. Curious passers-by will also be able to join if an event hasn’t been completed with its desired number of participants to keep enabling social fermentation.

4. An open space

The connection to the university gives the project the status of a school experiment, more than an intensive production space. As opposed to shared gardens that would be locked at night, the idea is to experiment with the forest as it was done in Taiwan, counting on the trust and good will of the community to respect its openness.

Some users of the space, such as dog walkers, have already been identified as stakeholders that should be considered in the design of the forest. The working group has conducted interviews to integrate their needs to the design process from the beginning, thinking of strategies to involve non-humans in the circular forest. Dedicating the dog walking area to tall trees or material production are current options that will allow the project to be sustainable due to common agreements.

2. The working group as a core

As the Vielwald is located close to the design school, the working group of students is the connecting element between the two spaces. Communicating across the neighbourhood and exploring ways for local neighbours to engage will be a first step, to then take care of the space and organise activities to eventually grow food and materials across the seasons. Families, shop owners, regular visitors of the space can take part and benefit from the initiative, through harvests but also through shared plant knowledge.

3. An activity-based system

The system of the Vielwald will work organically: a designated platform will be placed on site for visitors to sign up for the next events. People who contributed will also receive an invitation to the harvest days. The workshops of the design school will be used to build infrastructures and transform the products of the forest, with external actors joining within dedicated events. Curious passers-by will also be able to join if an event hasn’t been completed with its desired number of participants to keep enabling social fermentation.

4. An open space

The connection to the university gives the project the status of a school experiment, more than an intensive production space. As opposed to shared gardens that would be locked at night, the idea is to experiment with the forest as it was done in Taiwan, counting on the trust and good will of the community to respect its openness.

1. Clara Schmeinck and Anna Luz Pueyo

Clara Schmeinck and Anna Luz Pueyo are the creators of a project initiated in 2019. Clara is the founder of the circular material library at KISD and has worked at the ZHDK material library in Zurich. Anna Luz focuses on forest gardening research and exploring the lost uses of trees. Together, they guide a student working group, drawing from their expertise.

2. Prof. Heidkamp and the Working Group

The project began within a design project led by Prof. Philip Heidkamp, who has since mentored the initiative. Heidkamp is well-connected in the European design community, being part of the Cumulus consortium and Medes program. In spring 2023, a working group was formed, consisting of 15 students, including representative Lennard Poppe. The group is responsible for designing the space, with leadership rotating each semester under Prof. Heidkamp's guidance.

3. Support from Local Associations

Since its creation, the project has gained support from local organizations such as the Committee for Edible Cities and Urban Agriculture. Their collaboration has connected the project to a wider network of contributors, grounding it in the local context. Since 2024, the group has also worked with NeuLand, a community garden in the neighborhood that is cultivating a forest garden in public space. The students have been learning and applying forest gardening techniques with NeuLand.

4. Collaboration with the City of Cologne

The project works closely with the Department of Green Spaces in Cologne. With support from M. Hölzer from the Office for Landscape Conservation and Green Spaces, the project is defining a space near the design school. This political support from the city strengthens the project's foundation.

5. The Forest Garden Movement

The project has also been shaped by the forest garden movement, which gained insight from a visit to Taiwan and continued communication with European actors in the field.

Clara Schmeinck and Anna Luz Pueyo are the creators of a project initiated in 2019. Clara is the founder of the circular material library at KISD and has worked at the ZHDK material library in Zurich. Anna Luz focuses on forest gardening research and exploring the lost uses of trees. Together, they guide a student working group, drawing from their expertise.

2. Prof. Heidkamp and the Working Group

The project began within a design project led by Prof. Philip Heidkamp, who has since mentored the initiative. Heidkamp is well-connected in the European design community, being part of the Cumulus consortium and Medes program. In spring 2023, a working group was formed, consisting of 15 students, including representative Lennard Poppe. The group is responsible for designing the space, with leadership rotating each semester under Prof. Heidkamp's guidance.

3. Support from Local Associations

Since its creation, the project has gained support from local organizations such as the Committee for Edible Cities and Urban Agriculture. Their collaboration has connected the project to a wider network of contributors, grounding it in the local context. Since 2024, the group has also worked with NeuLand, a community garden in the neighborhood that is cultivating a forest garden in public space. The students have been learning and applying forest gardening techniques with NeuLand.

4. Collaboration with the City of Cologne

The project works closely with the Department of Green Spaces in Cologne. With support from M. Hölzer from the Office for Landscape Conservation and Green Spaces, the project is defining a space near the design school. This political support from the city strengthens the project's foundation.

5. The Forest Garden Movement

The project has also been shaped by the forest garden movement, which gained insight from a visit to Taiwan and continued communication with European actors in the field.

To design the circular forest, we tangled disciplines from the field of agroecology with our own design skills.

1. Botanic

We adapted the concept studied in Taiwan to our European context, reaching out to German gardeners to select plants adapted to the climate of Cologne for all layers of the forest. This research was translated into a hand drawn plant database.

2. Permaculture

We borrowed principles from permaculture, such as hügels (raised beds), hedges and keyhole plantations to bring a 3D dimension to the space, as a way to manage shadows, winds and rainwater flows. In April 2024, we organized a workshop with Claire Mauquié, who designed the food forests in Hsinchu, to bring together a first forest garden design. Further, we took inspiration from light infrastructures (growing towers, vine tunnels, compost bins), redesigning them into versions that could be easily built in the school workshops.

3. Regenerative agriculture

Our contact Maxime Leloup, from Ver de Terre production, will help us consider which solutions are best to recreate a rich and living soil. We already know that a compost bank will have to be set up, and we see this as a way to collaborate with local restaurants, florists and coffee shops, collecting their organic waste to create our living soil.

4. Participatory design

Our participatory design skills are used all along the project to communicate with citizens, starting with interview tools.To ensure collaborative decision-making, we also designed the “value wheels”, a tool to evaluate key moments where volunteers would like to participate, the most important objectives for the community and the types of plants they would like to grow.

5. Mapping and graphic design

Mapping the space allowed us to study the topography of the space to envision water management, sound and sun exposure. This map will evolve to place the future plants and envision their growth in the future, as well as a means of communication to the public.

1. Botanic

We adapted the concept studied in Taiwan to our European context, reaching out to German gardeners to select plants adapted to the climate of Cologne for all layers of the forest. This research was translated into a hand drawn plant database.

2. Permaculture

We borrowed principles from permaculture, such as hügels (raised beds), hedges and keyhole plantations to bring a 3D dimension to the space, as a way to manage shadows, winds and rainwater flows. In April 2024, we organized a workshop with Claire Mauquié, who designed the food forests in Hsinchu, to bring together a first forest garden design. Further, we took inspiration from light infrastructures (growing towers, vine tunnels, compost bins), redesigning them into versions that could be easily built in the school workshops.

3. Regenerative agriculture

Our contact Maxime Leloup, from Ver de Terre production, will help us consider which solutions are best to recreate a rich and living soil. We already know that a compost bank will have to be set up, and we see this as a way to collaborate with local restaurants, florists and coffee shops, collecting their organic waste to create our living soil.

4. Participatory design

Our participatory design skills are used all along the project to communicate with citizens, starting with interview tools.To ensure collaborative decision-making, we also designed the “value wheels”, a tool to evaluate key moments where volunteers would like to participate, the most important objectives for the community and the types of plants they would like to grow.

5. Mapping and graphic design

Mapping the space allowed us to study the topography of the space to envision water management, sound and sun exposure. This map will evolve to place the future plants and envision their growth in the future, as well as a means of communication to the public.

1. Deep regeneration

Recreating a forest environment in a city is innovative in itself, as public green spaces are often very structured and limited in terms of interactions. Compared to shared gardens or urban greening initiatives that are often off-soil cultures, the core of this project is to deeply regenerate the soil of a patch of land. In contrast to city woods and forests that are often used as spaces of leisure and contemplation, the idea is to bring the interactions with trees in the center of the process.

2. Low maintenance

A forest can be resilient after five to ten years of maintenance, and it can pretty much take care of itself after that, meaning that the first push from the citizens is the most important. In the years after, the forest can integrate fully in the cityscape and provide more and more food and materials for the community. This longevity can engage municipalities in the long run, which is a good way to make sure that sustainable public policies are maintained. The resilience and generosity of this model are what make it so unique.

3. A unique partnership

The specificity of our project is also the link we want to create between the forest and an international school of design (KISD). The governance model based on a working group that is maintained over the years means that the responsibility for this space is shared among different actors, with a teacher figure (P. Heidkamp) and ourselves (A. Pueyo and C. Schmeinck) as initiators and coordinators.

4. A rich design practice

We strongly believe that working on the graphical communication of the project, designing rituals and infrastructures for this space, as well as documenting the different types of harvests and their applications can be great exercises for design students, giving space for agroforestry in the design culture. Sharing this practice with the neighborhood will also root the school in its local environment, creating an unmatched sense of belonging for both.

Recreating a forest environment in a city is innovative in itself, as public green spaces are often very structured and limited in terms of interactions. Compared to shared gardens or urban greening initiatives that are often off-soil cultures, the core of this project is to deeply regenerate the soil of a patch of land. In contrast to city woods and forests that are often used as spaces of leisure and contemplation, the idea is to bring the interactions with trees in the center of the process.

2. Low maintenance

A forest can be resilient after five to ten years of maintenance, and it can pretty much take care of itself after that, meaning that the first push from the citizens is the most important. In the years after, the forest can integrate fully in the cityscape and provide more and more food and materials for the community. This longevity can engage municipalities in the long run, which is a good way to make sure that sustainable public policies are maintained. The resilience and generosity of this model are what make it so unique.

3. A unique partnership

The specificity of our project is also the link we want to create between the forest and an international school of design (KISD). The governance model based on a working group that is maintained over the years means that the responsibility for this space is shared among different actors, with a teacher figure (P. Heidkamp) and ourselves (A. Pueyo and C. Schmeinck) as initiators and coordinators.

4. A rich design practice

We strongly believe that working on the graphical communication of the project, designing rituals and infrastructures for this space, as well as documenting the different types of harvests and their applications can be great exercises for design students, giving space for agroforestry in the design culture. Sharing this practice with the neighborhood will also root the school in its local environment, creating an unmatched sense of belonging for both.

Research-by-design

To decide on the location for the Vielwald, the working group has been working on different methodologies to analyse the field and make the best diagnosis of it. Those methods imply user interviews, soil testing and mapping of all kinds of data : sound and light around the parcel, local existing species, water supplies, compost sources and potential partners and nearby institutions. This research also involves participatory tools to start testing the temperature with the neighbours.

Regenerative

Once the data will be collected and the parcel will be allocated, the group will start working with the soil to recreate a rich base for a forest. This will imply collecting compost from local restaurants and using the pruned branches from the green services of the city. The mulch will be collected and left on the ground to decompose. Small installations such as compost containers can already be placed on the site to accelerate the process.

Co-design

The selection of plants and the spatial design of the forest will be done by the students of the working group, in collaboration with the local users of the site. Workshops will be organised onsite or at the KISD and collaborators such as school children and elderly people will be introduced to the project in dedicated formats, and those groups will be involved in the creation of a small plant nursery hosted at the KISD. The plantation phase will be a collaborative moment, where everyone will be able to join. Once the forest is planted, the activities will be hosted by the students from the design school, with different target groups : either completely open or dedicated to specific local partners. This will make sure that everyone close to the space will have the opportunity to participate in the project.

To decide on the location for the Vielwald, the working group has been working on different methodologies to analyse the field and make the best diagnosis of it. Those methods imply user interviews, soil testing and mapping of all kinds of data : sound and light around the parcel, local existing species, water supplies, compost sources and potential partners and nearby institutions. This research also involves participatory tools to start testing the temperature with the neighbours.

Regenerative

Once the data will be collected and the parcel will be allocated, the group will start working with the soil to recreate a rich base for a forest. This will imply collecting compost from local restaurants and using the pruned branches from the green services of the city. The mulch will be collected and left on the ground to decompose. Small installations such as compost containers can already be placed on the site to accelerate the process.

Co-design

The selection of plants and the spatial design of the forest will be done by the students of the working group, in collaboration with the local users of the site. Workshops will be organised onsite or at the KISD and collaborators such as school children and elderly people will be introduced to the project in dedicated formats, and those groups will be involved in the creation of a small plant nursery hosted at the KISD. The plantation phase will be a collaborative moment, where everyone will be able to join. Once the forest is planted, the activities will be hosted by the students from the design school, with different target groups : either completely open or dedicated to specific local partners. This will make sure that everyone close to the space will have the opportunity to participate in the project.

1. Universal Agroforestry

As it has been proven in the past, agroforestry can exist in most regions of the world, as long as trees can grow. Before the industrial revolution, systems of culture based around the tree were common in Europe, as it is still the case in Portugal with the patanegra pigs being fed from acorns.

Our own iteration of this model, Vielwald, is designed for cities, but it can equally be replicated elsewhere. As our research has shown, urban forests can be grown in Taiwan, in the south of France but also in England where the first food forests came to life, in the hands of Robert Hart. Local experts will have to be consulted for the plant and soil management because the vegetation will always have to be adapted to its context. But the main principle of using pruned wood and compost to regenerate the soil can be used across contexts.

2. Open designs

On the other hand, the growing principles can remain the same, with the different stratas of plants interacting with each other in a supportive system. Raised beds and keyhole gardens, as well as spaces kept wild can be replicated on most fields, but their design in the space will have to be decided according to the topography and weather conditions.

The tools we adapted for the project such as growing towers, compost bins, vine tunnels and herb spirals are low-tech designs that can be reproduced elsewhere with simple materials.

Similarly, the participation tools we developed such as the value wheels can be used across all contexts for decision-making.

3. Methodology

If the collaboration between the school, the forest and the neighborhood is successful, this could be a model replicable to similar city constellations. Design schools can therefore be seen as hubs, anchored to their local context through plants and the products they can experiment with. Hosting KISD partner European schools such as Rotterdam or Barcelona could be the occasion to teach them how to replicate the model.

As it has been proven in the past, agroforestry can exist in most regions of the world, as long as trees can grow. Before the industrial revolution, systems of culture based around the tree were common in Europe, as it is still the case in Portugal with the patanegra pigs being fed from acorns.

Our own iteration of this model, Vielwald, is designed for cities, but it can equally be replicated elsewhere. As our research has shown, urban forests can be grown in Taiwan, in the south of France but also in England where the first food forests came to life, in the hands of Robert Hart. Local experts will have to be consulted for the plant and soil management because the vegetation will always have to be adapted to its context. But the main principle of using pruned wood and compost to regenerate the soil can be used across contexts.

2. Open designs

On the other hand, the growing principles can remain the same, with the different stratas of plants interacting with each other in a supportive system. Raised beds and keyhole gardens, as well as spaces kept wild can be replicated on most fields, but their design in the space will have to be decided according to the topography and weather conditions.

The tools we adapted for the project such as growing towers, compost bins, vine tunnels and herb spirals are low-tech designs that can be reproduced elsewhere with simple materials.

Similarly, the participation tools we developed such as the value wheels can be used across all contexts for decision-making.

3. Methodology

If the collaboration between the school, the forest and the neighborhood is successful, this could be a model replicable to similar city constellations. Design schools can therefore be seen as hubs, anchored to their local context through plants and the products they can experiment with. Hosting KISD partner European schools such as Rotterdam or Barcelona could be the occasion to teach them how to replicate the model.

SDG Goals

Growing a productive forest addresses ten of the seventeen Sustainable Development goals set by the United Nations. Those are: zero hunger (2), good health and well-being (3), quality education (4), reduced inequality (10), sustainable cities and communities (11), responsible consumption and production (12), climate action (13), life on land (15), peace, justice and strong institutions (16) and partnerships to achieve the goal (17).

Self-sufficiency

Globally, our concept wants to change the perception of products amongst consumers, to make them actors of their own consumption through design. Self-sufficiency is the long-term objective, to reduce imports and fight the wasteful production chains of the linear economy. On a global level, the project turns public space into a productive space, fighting the loss of agricultural land and food insecurity while closing cycles of production and consumption. Envisioning full production chains will get mentalities to evolve and believe that we can craft our daily products ourselves.

Connecting to plants

The database of plants will be shared internationally, feeding into the global culture on plant knowledge. Physical activities such as planting and eating fresh produce will improve physical and mental health conditions and collaboration across cultures and generations will help sustain a friendly and inclusive society.

Patches that are transformed into forest grounds will provide porous land to absorb excess waters, fresh environments to fight climate change and sane soils to prevent excess pollution. As well as beautiful environments for humans and non humans.

We want to emphasize that this initiative has been clearly inspired by our case study in Taiwan. Seeing our project come to life can similarly motivate others to follow our example. If the movement spreads, all of the benefits that we are listing will be multiplied, which brings out the importance of funding our own initiative in the first place.

Growing a productive forest addresses ten of the seventeen Sustainable Development goals set by the United Nations. Those are: zero hunger (2), good health and well-being (3), quality education (4), reduced inequality (10), sustainable cities and communities (11), responsible consumption and production (12), climate action (13), life on land (15), peace, justice and strong institutions (16) and partnerships to achieve the goal (17).

Self-sufficiency

Globally, our concept wants to change the perception of products amongst consumers, to make them actors of their own consumption through design. Self-sufficiency is the long-term objective, to reduce imports and fight the wasteful production chains of the linear economy. On a global level, the project turns public space into a productive space, fighting the loss of agricultural land and food insecurity while closing cycles of production and consumption. Envisioning full production chains will get mentalities to evolve and believe that we can craft our daily products ourselves.

Connecting to plants

The database of plants will be shared internationally, feeding into the global culture on plant knowledge. Physical activities such as planting and eating fresh produce will improve physical and mental health conditions and collaboration across cultures and generations will help sustain a friendly and inclusive society.

Patches that are transformed into forest grounds will provide porous land to absorb excess waters, fresh environments to fight climate change and sane soils to prevent excess pollution. As well as beautiful environments for humans and non humans.

We want to emphasize that this initiative has been clearly inspired by our case study in Taiwan. Seeing our project come to life can similarly motivate others to follow our example. If the movement spreads, all of the benefits that we are listing will be multiplied, which brings out the importance of funding our own initiative in the first place.

Winter : planning and designing

The planning of the circular forest follows the natural rhythm of the year, because the growing seasons of the plants have to be taken into account. The cold months of the year will mainly be used to let locals vote for their preferred activities and plants and prepare the soil with pruned wood. The design of the circular forest will take shape from the start of the 2025 Winter semester.

Spring : preparing and seeding

The blooming months will be split between preparing the soil to create a rich humus necessary for plants to grow in the summer and installing a rainwater collection system to prevent any droughts in the summer. The field study of the working group will be completed by a workshop with our expert contacts, to learn how to design according to factors such as soil quality, sun exposure, annual temperatures etc. The final design will be decided, in consultation with the local users of the space, and the plant nursery will be initiated in collaboration with the local school and elderly home.

Summer : planting and maintaining

In the hot months, there will be a lot of work for everyone so workshops will be offered by the working group every week on the field. Workshops will already be organised at the KISD to build growing systems. At the end of the summer, a first event will be organised to share the first food and connect the participants.

Autumn : preserving and reflecting

After the summer, workshops will be planned in the food lab to preserve the harvest and share it with participants or at the Christmas markets. A focus on specific plants grown in the forest will be integrated to the Winter semester curriculum to have projects from students activating the space. As the end of the year approaches, we will look back at the process so far and reflect on our learnings. A moment to plan the next year will be necessary in order to pitch the newcomers and set a vision for the future.

The planning of the circular forest follows the natural rhythm of the year, because the growing seasons of the plants have to be taken into account. The cold months of the year will mainly be used to let locals vote for their preferred activities and plants and prepare the soil with pruned wood. The design of the circular forest will take shape from the start of the 2025 Winter semester.

Spring : preparing and seeding

The blooming months will be split between preparing the soil to create a rich humus necessary for plants to grow in the summer and installing a rainwater collection system to prevent any droughts in the summer. The field study of the working group will be completed by a workshop with our expert contacts, to learn how to design according to factors such as soil quality, sun exposure, annual temperatures etc. The final design will be decided, in consultation with the local users of the space, and the plant nursery will be initiated in collaboration with the local school and elderly home.

Summer : planting and maintaining

In the hot months, there will be a lot of work for everyone so workshops will be offered by the working group every week on the field. Workshops will already be organised at the KISD to build growing systems. At the end of the summer, a first event will be organised to share the first food and connect the participants.

Autumn : preserving and reflecting

After the summer, workshops will be planned in the food lab to preserve the harvest and share it with participants or at the Christmas markets. A focus on specific plants grown in the forest will be integrated to the Winter semester curriculum to have projects from students activating the space. As the end of the year approaches, we will look back at the process so far and reflect on our learnings. A moment to plan the next year will be necessary in order to pitch the newcomers and set a vision for the future.