Regaining a sense of belonging

Social and urban infill project

Revitalization of a former garden neighbourhood in Kortrijk, a social and urban infill project.

The original garden city concept, where private gardens connect to a central green space, has largely disappeared in this neighbourhood. Many gardens turned into garages or enclosed extensions, disrupting connections between homes and neighbours. This project revitalizes the inner area, transforming the back into a second front while enhancing home quality and flexibility. By focusing on participation and material reuse, social and societal concerns are identified and integrated into the project

Belgium

Local

Kortrijk

Mainly urban

It refers to a physical transformation of the built environment (hard investment)

Yes

2024-10-25

No

No

Yes

Yes

Yes

As a representative of an organisation, in partnership with other organisations

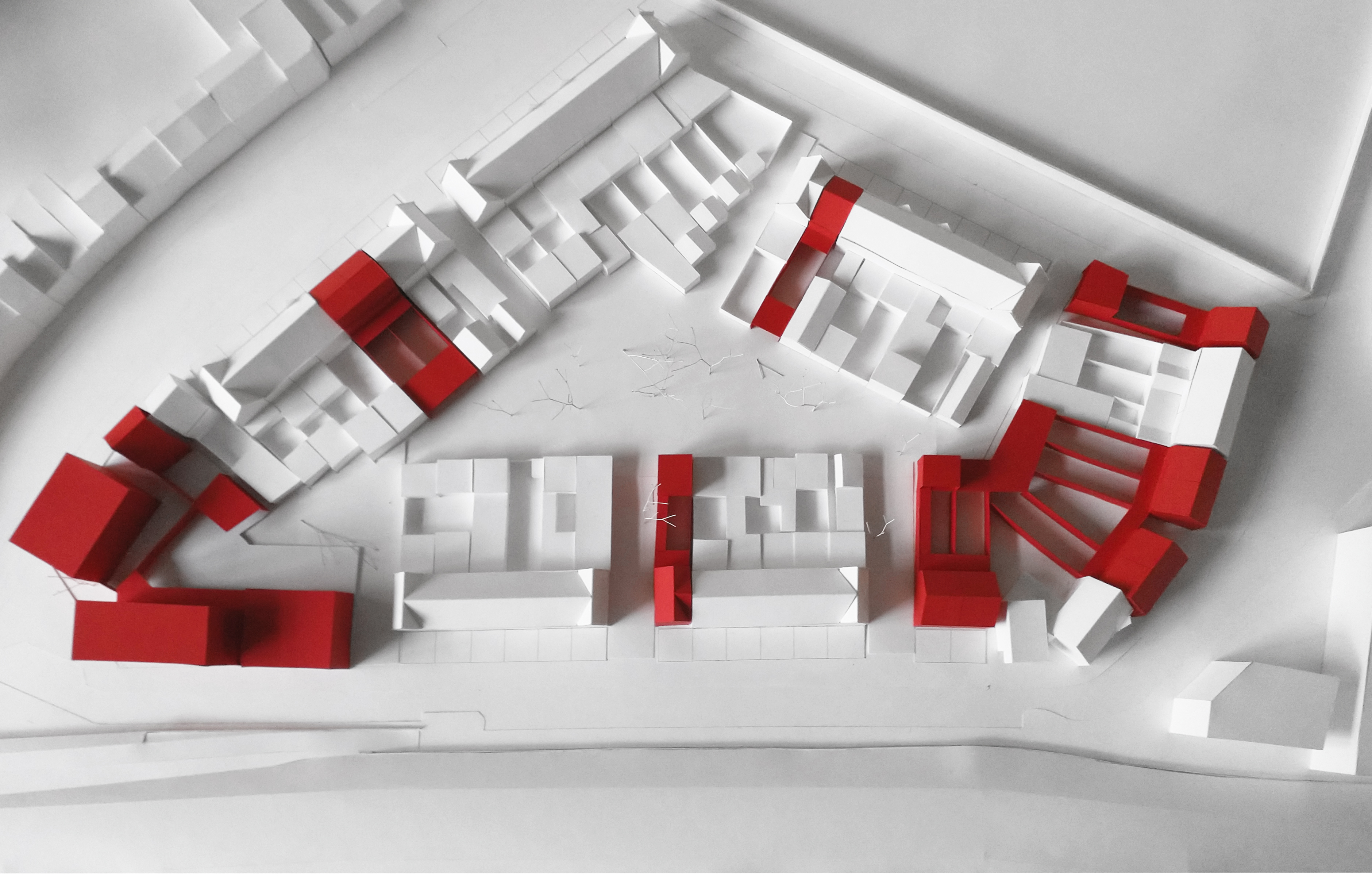

The original Garden City concept, which once united workers' homes around a communal green space, has largely disappeared in the Tuighuisstraat in Kortrijk. Today, garage doors and closed facades form a continuous barrier along an asphalted road, severing connections between homes and the inner area, diminishing the value of public space. This project reclaims the rear façades, transforming them into a second front.

The project is part of a neighbourhood with 54 homes, originally built in 1924 by the social housing company. Many houses have since been sold, leaving 18 plots under public ownership. This distribution enables a strategic intervention that revitalizes the neighbourhood—without full demolition or starting from scratch. By building on the existing footprint, the project densifies from 16 to 31 housing units, introducing flexible typologies for lifelong living and a ground-floor collective space to strengthen social cohesion.

The redevelopment enhances the quality of life not only for the 69 families in the neighbourhood but also for surrounding residents and passersby. The greened inner area becomes a permeable link within the urban fabric, integrating the neighbourhood into the broader city network. This improved connectivity prevents social isolation of lower-income families and fosters inclusion.

We build on the idea that users’ memories and roots anchor social cohesion. These are integrated through interviews, participatory processes, and co-construction.

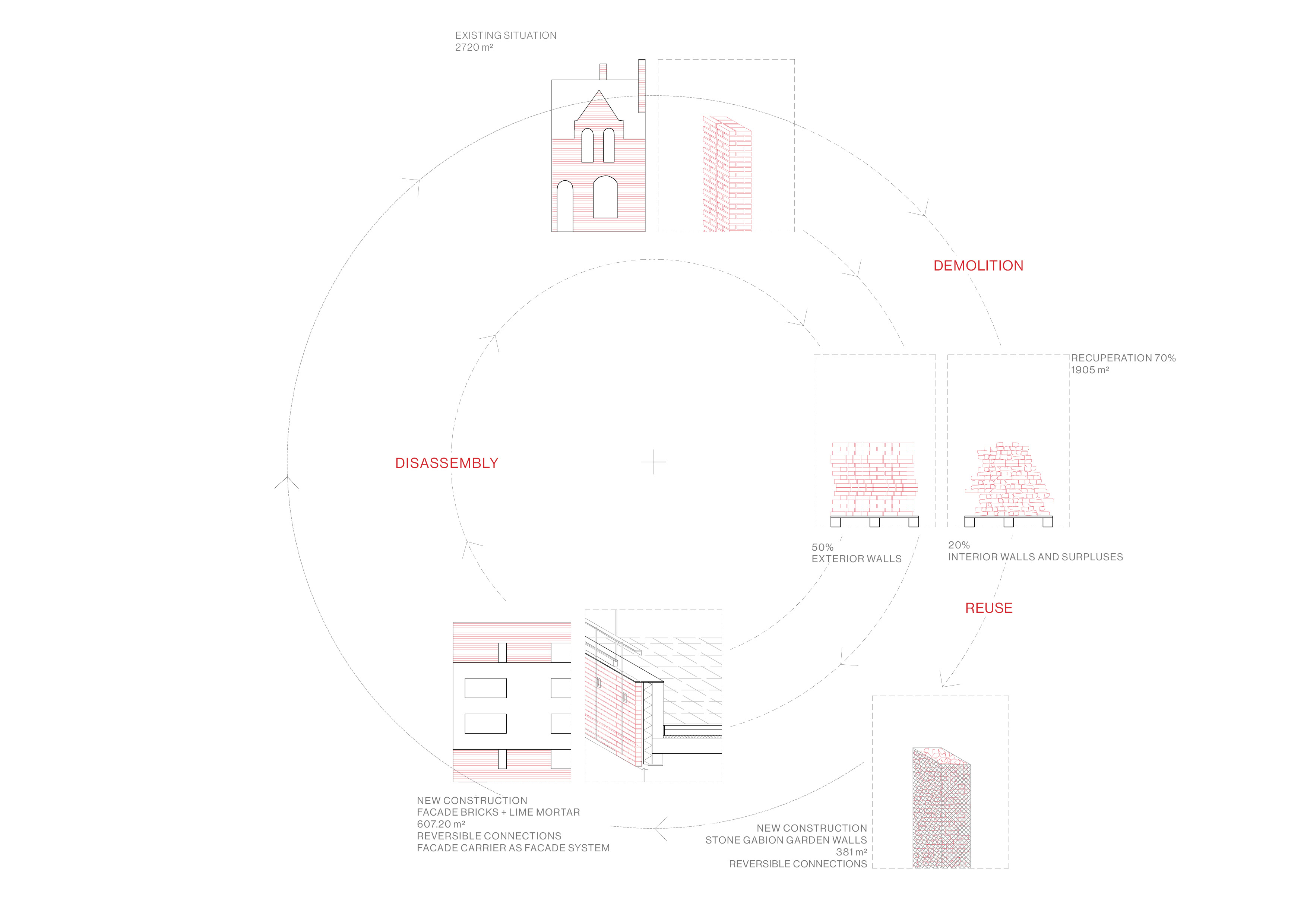

Materials influence more than their physical surroundings. This project creates a resilient framework across multiple scales to address evolving needs. Even individual building components shape the urban landscape. Where does a material come from? How sustainably is it used? By reusing in-situ materials, we extend the site’s narrative, raising awareness of the built environment’s value and promoting respect for materials—ensuring they are not prematurely discarded as waste.

The project is part of a neighbourhood with 54 homes, originally built in 1924 by the social housing company. Many houses have since been sold, leaving 18 plots under public ownership. This distribution enables a strategic intervention that revitalizes the neighbourhood—without full demolition or starting from scratch. By building on the existing footprint, the project densifies from 16 to 31 housing units, introducing flexible typologies for lifelong living and a ground-floor collective space to strengthen social cohesion.

The redevelopment enhances the quality of life not only for the 69 families in the neighbourhood but also for surrounding residents and passersby. The greened inner area becomes a permeable link within the urban fabric, integrating the neighbourhood into the broader city network. This improved connectivity prevents social isolation of lower-income families and fosters inclusion.

We build on the idea that users’ memories and roots anchor social cohesion. These are integrated through interviews, participatory processes, and co-construction.

Materials influence more than their physical surroundings. This project creates a resilient framework across multiple scales to address evolving needs. Even individual building components shape the urban landscape. Where does a material come from? How sustainably is it used? By reusing in-situ materials, we extend the site’s narrative, raising awareness of the built environment’s value and promoting respect for materials—ensuring they are not prematurely discarded as waste.

Enhancing social cohesion and inclusion at both neighbourhood and housing level

Engaging residents through dialogue and active participation

Innovative housing models that support lifelong and adaptable living

On-site reuse of bricks and roof tiles

Stimulating local economies

Sustainable housing is more than just architecture or buildings. This project takes a multi-scale approach, addressing levels from the neighbourhood to building components, connecting the bigger picture with the details.

At the neighborhood level, we focus on resilience and diversity, reinforcing social structures and biodiversity. This year, the inner area will be freed from cars, depaved, and re-greened, allowing rainwater to infiltrate. Existing trees will be preserved, and new pedestrian pathways will weave through blue-green zones.

At the plot level, we restore relationships with green and public spaces while introducing diverse housing types for different lifestyles.

At the building level, rational construction, climate- and material-responsive design, and adaptability are key. Dimensionally consistent solid construction is applied to apartments and main houses. To enhance adaptability and scalability of rear extensions, timber-frame construction is used. These buildings can evolve from a covered outdoor space into full residential or work units through extra insulation and vertical extensions. The structural work serves as the finishing layer.

We balance material impact, energy use, and environmental footprint. By integrating low-tech solutions to maintain a comfortable indoor climate—harnessing daylight, thermal mass, and natural ventilation—the architecture reduces the impact of heat and cold, significantly lowering energy demand.

At the material level, reclaimed facade bricks and clay tiles are reused on-site. The recovered materials have been tested. Bricks that don’t meet standards are placed in gabions as property boundaries. To ensure facade bricks of the new construction can also be reclaimed later, a hybrid mortar was selected after testing compositions.

Material reuse—along with deviations from standard specifications and construction processes—is uncommon in Belgium’s social housing market. However, thanks to a committed client, we succeeded.

At the neighborhood level, we focus on resilience and diversity, reinforcing social structures and biodiversity. This year, the inner area will be freed from cars, depaved, and re-greened, allowing rainwater to infiltrate. Existing trees will be preserved, and new pedestrian pathways will weave through blue-green zones.

At the plot level, we restore relationships with green and public spaces while introducing diverse housing types for different lifestyles.

At the building level, rational construction, climate- and material-responsive design, and adaptability are key. Dimensionally consistent solid construction is applied to apartments and main houses. To enhance adaptability and scalability of rear extensions, timber-frame construction is used. These buildings can evolve from a covered outdoor space into full residential or work units through extra insulation and vertical extensions. The structural work serves as the finishing layer.

We balance material impact, energy use, and environmental footprint. By integrating low-tech solutions to maintain a comfortable indoor climate—harnessing daylight, thermal mass, and natural ventilation—the architecture reduces the impact of heat and cold, significantly lowering energy demand.

At the material level, reclaimed facade bricks and clay tiles are reused on-site. The recovered materials have been tested. Bricks that don’t meet standards are placed in gabions as property boundaries. To ensure facade bricks of the new construction can also be reclaimed later, a hybrid mortar was selected after testing compositions.

Material reuse—along with deviations from standard specifications and construction processes—is uncommon in Belgium’s social housing market. However, thanks to a committed client, we succeeded.

The old bricks form the foundation for a new identity within the neighbourhood, preserving the history of the past while shaping a sustainable future.

The façade composition is guided by the availability of reclaimed bricks and the assembly method. Layers of reused bricks are combined with new ones. The mortar composition was tested to ensure it remains recoverable at the end of the building’s lifecycle. Mortar is either flush-finished or applied with a protruding joint to reduce residue and eliminate the need for repointing.

The involvement of residents in stacking the reclaimed bricks into the gabions was a way to engage them in the construction process and allow them to influence its aesthetic outcome. By directly handling the materials, they develop a deeper respect for both the materials themselves and the built environment.

Brick construction has long been integral to the Belgian cultural heritage. It is not just a building material, but a part of our identity, deeply embedded in the social and economic fabric of the region. The use of brick represents a rich tradition, linking generations through its craftsmanship, local expertise, and industrial legacy. By reusing these bricks, we not only maintain a physical connection to the past but also reinvigorate a practice that contributes to both the local economy and the environment.

This exemplary approach to construction, where history, participation and sustainability are interwoven, offers a new aesthetics and a sense of continuity and resilience—qualities that will endure long after the building’s completion.

The façade composition is guided by the availability of reclaimed bricks and the assembly method. Layers of reused bricks are combined with new ones. The mortar composition was tested to ensure it remains recoverable at the end of the building’s lifecycle. Mortar is either flush-finished or applied with a protruding joint to reduce residue and eliminate the need for repointing.

The involvement of residents in stacking the reclaimed bricks into the gabions was a way to engage them in the construction process and allow them to influence its aesthetic outcome. By directly handling the materials, they develop a deeper respect for both the materials themselves and the built environment.

Brick construction has long been integral to the Belgian cultural heritage. It is not just a building material, but a part of our identity, deeply embedded in the social and economic fabric of the region. The use of brick represents a rich tradition, linking generations through its craftsmanship, local expertise, and industrial legacy. By reusing these bricks, we not only maintain a physical connection to the past but also reinvigorate a practice that contributes to both the local economy and the environment.

This exemplary approach to construction, where history, participation and sustainability are interwoven, offers a new aesthetics and a sense of continuity and resilience—qualities that will endure long after the building’s completion.

We believe it is essential to understand the story behind both people and materials. In this project, our focus extends beyond the final result to the process itself. Neither users nor materials are static; they exist within a timeline, carrying both a history and a future. By embracing this perspective, we can minimize environmental impact and maximize social impact.

Through interviews and participatory processes, we identified key challenges such as social isolation and a lack of communal cohesion and interaction with public spaces. Residents expressed a need for better connections with public spaces. In response, we co-created a more accessible and interconnected neighbourhood. We increased permeability by opening passageways and strengthening links with the surrounding urban fabric. By constructing around the central inner area to energize it with social interactions, we strengthened the relationship between homes and public space. Additionally, we integrated communal spaces at strategic nodes in the neighbourhood, including a multipurpose space for meetings and community activities on the ground floor of the apartment buildings.

The number of blended families, work-live arrangements, and fluctuating life paths is increasing. Families need flexibility to expand or downsize while staying in the same location. The project aims to offer a variety of housing solutions. By expanding the homes and adding new functions to the rear boundary of the plot, the neighbourhood will be transformed to accommodate contemporary and complementary living styles, including intergenerational housing, students or newcomers living at home, live-in elderly, guest rooms, and flexible housing for newly blended families. This approach revitalizes both the homes and the surrounding area, activating the interior public space, improving social safety, and restoring the connection between the home and the public domain.

Through interviews and participatory processes, we identified key challenges such as social isolation and a lack of communal cohesion and interaction with public spaces. Residents expressed a need for better connections with public spaces. In response, we co-created a more accessible and interconnected neighbourhood. We increased permeability by opening passageways and strengthening links with the surrounding urban fabric. By constructing around the central inner area to energize it with social interactions, we strengthened the relationship between homes and public space. Additionally, we integrated communal spaces at strategic nodes in the neighbourhood, including a multipurpose space for meetings and community activities on the ground floor of the apartment buildings.

The number of blended families, work-live arrangements, and fluctuating life paths is increasing. Families need flexibility to expand or downsize while staying in the same location. The project aims to offer a variety of housing solutions. By expanding the homes and adding new functions to the rear boundary of the plot, the neighbourhood will be transformed to accommodate contemporary and complementary living styles, including intergenerational housing, students or newcomers living at home, live-in elderly, guest rooms, and flexible housing for newly blended families. This approach revitalizes both the homes and the surrounding area, activating the interior public space, improving social safety, and restoring the connection between the home and the public domain.

The involvement of the residents took place in two steps. First, through interviews with the existing residents of the neighbourhood, and then through participation with both current and new residents. Both initiatives provided valuable information, which we incorporated into the project.

The one-on-one conversations with existing residents before the project began allowed us to treat them as individuals, rather than as a group. This approach gave everyone the opportunity to share their needs and concerns in a comfortable manner, including the less outspoken residents. Some families had lived in the neighbourhood for generations and had witnessed its transformation. Most of them reported a decline in safety, social control, and sense of community. Parents no longer felt comfortable letting their children play freely in the central courtyard. By improving accessibility, strengthening the relationship between housing and public space through new housing typologies, redesigning the inner area, and introducing a community space, we were able to address these concerns.

The participation process was organized through several group sessions for both existing and newly interested residents. The participation mainly focused on three themes: the redesign of the inner area, the use of the community space, and the placement of reclaimed bricks in gabions for property boundaries. The latter was a co-creation process in which the local social workshop assisted and guided residents in filling the gabions.

The redesign of the inner area has yet to take place. The project has taken into account residents' requests for more green spaces, fewer car-related facilities, play areas for children, and a shared storage facility (which has already been implemented). The community space will become a multifunctional area for family or neighbourhood gatherings.

The one-on-one conversations with existing residents before the project began allowed us to treat them as individuals, rather than as a group. This approach gave everyone the opportunity to share their needs and concerns in a comfortable manner, including the less outspoken residents. Some families had lived in the neighbourhood for generations and had witnessed its transformation. Most of them reported a decline in safety, social control, and sense of community. Parents no longer felt comfortable letting their children play freely in the central courtyard. By improving accessibility, strengthening the relationship between housing and public space through new housing typologies, redesigning the inner area, and introducing a community space, we were able to address these concerns.

The participation process was organized through several group sessions for both existing and newly interested residents. The participation mainly focused on three themes: the redesign of the inner area, the use of the community space, and the placement of reclaimed bricks in gabions for property boundaries. The latter was a co-creation process in which the local social workshop assisted and guided residents in filling the gabions.

The redesign of the inner area has yet to take place. The project has taken into account residents' requests for more green spaces, fewer car-related facilities, play areas for children, and a shared storage facility (which has already been implemented). The community space will become a multifunctional area for family or neighbourhood gatherings.

Throughout the entire process, there was continuous and intensive collaboration with the city services of Kortrijk (the permitting authority), Wonen in Vlaanderen (the subsidizing authority), and the social housing company SW+ (the developer).

Involving the city of Kortrijk was essential, as building additional housing units on the same plot—particularly around the inner area—is not a common practice. The city also played a crucial role in the redevelopment of the inner area, which will become public space.

Wonen in Vlaanderen imposes various requirements for social housing in Flanders, including cost-efficient construction, minimum and maximum living space standards, and specific housing typologies. This authority was not only instrumental in securing funding but also in approving deviations from standard housing typologies. Thanks to early involvement and a clear understanding of the rationale behind these deviations, approval was successfully obtained.

As the developer, SW+ was the project’s most significant stakeholder. Integrating new housing concepts and using reclaimed materials were not standard practices for them, but their shared commitment to sustainability and circular construction encouraged them to take this step.

Without the support of these three stakeholders, the project’s ambitions could not have been realized.

Involving the city of Kortrijk was essential, as building additional housing units on the same plot—particularly around the inner area—is not a common practice. The city also played a crucial role in the redevelopment of the inner area, which will become public space.

Wonen in Vlaanderen imposes various requirements for social housing in Flanders, including cost-efficient construction, minimum and maximum living space standards, and specific housing typologies. This authority was not only instrumental in securing funding but also in approving deviations from standard housing typologies. Thanks to early involvement and a clear understanding of the rationale behind these deviations, approval was successfully obtained.

As the developer, SW+ was the project’s most significant stakeholder. Integrating new housing concepts and using reclaimed materials were not standard practices for them, but their shared commitment to sustainability and circular construction encouraged them to take this step.

Without the support of these three stakeholders, the project’s ambitions could not have been realized.

The creative process fostered diverse collaborations with experts from different fields. Reuse requires specialized skills and, as a result, creates new professional roles. Dismantling, restoring, and adapting materials demand more care and time than demolition and disposal, stimulating local businesses and employment.

Once the materials were recovered, they were measured, inventoried, and cataloged. Accurate and detailed information was essential for the successful reuse of each component.

The project brought together specialists from both within and outside the team, including demolition contractors specialized in material recovery, material suppliers, laboratories for material testing, technical consultants, as well as "material collectors" and "component experts." The collaboration between craftsmen and designers was particularly close and dynamic, allowing them to find the best solutions together.

Preserving resources and advancing a circular economy is both a global challenge and a shared responsibility. MAKER architecten therefore strongly emphasize knowledge exchange. This exchange benefits everyone, as it enables the sharing of expertise and the comparison of local conditions, leading to diverse applications. By learning from one another, valuable insights and best practices can be carried forward across different contexts.

The project has been published multiple times and presented at events organized by Vlaanderen Circulair, professional associations, social housing organizations, and universities. For the team, spreading knowledge is a key element in promoting circular construction and increasing its visibility.

The project has been published multiple times and presented at events organized by Vlaanderen Circulair, professional associations, social housing organizations, and universities. For the team, spreading knowledge is an essential aspect of promoting circular construction and increasing its visibility.

Once the materials were recovered, they were measured, inventoried, and cataloged. Accurate and detailed information was essential for the successful reuse of each component.

The project brought together specialists from both within and outside the team, including demolition contractors specialized in material recovery, material suppliers, laboratories for material testing, technical consultants, as well as "material collectors" and "component experts." The collaboration between craftsmen and designers was particularly close and dynamic, allowing them to find the best solutions together.

Preserving resources and advancing a circular economy is both a global challenge and a shared responsibility. MAKER architecten therefore strongly emphasize knowledge exchange. This exchange benefits everyone, as it enables the sharing of expertise and the comparison of local conditions, leading to diverse applications. By learning from one another, valuable insights and best practices can be carried forward across different contexts.

The project has been published multiple times and presented at events organized by Vlaanderen Circulair, professional associations, social housing organizations, and universities. For the team, spreading knowledge is a key element in promoting circular construction and increasing its visibility.

The project has been published multiple times and presented at events organized by Vlaanderen Circulair, professional associations, social housing organizations, and universities. For the team, spreading knowledge is an essential aspect of promoting circular construction and increasing its visibility.

Social housing in Belgium is governed by numerous regulations regarding surface areas, the number of bedrooms, construction costs, and building methods. These regulations are currently based on a traditional family structure (two parents with a set number of children) and a conventional way of living (bedrooms, kitchen, dining room, living room, and storage space). However, today’s family compositions and lifestyles are much more diverse.

With this project, we aim to demonstrate that social housing can accommodate new living models. There is a growing demand for both very small homes (for single-person households, often elderly individuals) and very large homes (for extended families or multi-generational households, often within immigrant communities).

The dual-unit concept allows for flexible use: it can function as a single unit for large families or as two separate entities. In the latter case, combining a “traditional” family with a single-person household creates a win-win situation, facilitated by a shared winter garden/hall and outdoor space. This setup fosters mutual support—offering companionship without obligation, informal supervision, and practical help, such as shared errands.

The dual units also respond to evolving living habits. Since COVID-19, the demand for home offices has increased. The separate unit provides a dedicated workspace, allowing residents to work from home without household disruptions.

Additionally, the reuse of materials is an innovative approach within social housing in Belgium.

With this project, we aim to demonstrate that social housing can accommodate new living models. There is a growing demand for both very small homes (for single-person households, often elderly individuals) and very large homes (for extended families or multi-generational households, often within immigrant communities).

The dual-unit concept allows for flexible use: it can function as a single unit for large families or as two separate entities. In the latter case, combining a “traditional” family with a single-person household creates a win-win situation, facilitated by a shared winter garden/hall and outdoor space. This setup fosters mutual support—offering companionship without obligation, informal supervision, and practical help, such as shared errands.

The dual units also respond to evolving living habits. Since COVID-19, the demand for home offices has increased. The separate unit provides a dedicated workspace, allowing residents to work from home without household disruptions.

Additionally, the reuse of materials is an innovative approach within social housing in Belgium.

The team's creative process follows a cyclical model, keeping creativity active and responsive. The design evolves continuously, with insights building upon each other to generate new perspectives.

Simultaneously, the process combines both top-down and bottom-up approaches. On one hand, the design must be strongly rooted in its urban and social context. On the other, the development of the buildings starts from the perspective of the people who will use them—residents, temporary occupants, and passersby.

We apply the principle of balancing macro and micro perspectives, always keeping both the broader vision and the smallest detail in focus. An iterative approach allows these perspectives to intersect, with feedback refining the process at key moments.

A deep knowledge of the existing conditions is essential to define the impact of interventions. Developing a master plan at multiple levels (neighbourhood-building-material) serves as a roadmap—both during and after construction.

🔹 Step 1: Listening & Understanding (Bottom-Up)

• Understanding the stories behind people—what are their needs, backgrounds, and daily challenges?

• Understanding the stories behind materials—where do they come from, and how can they be repurposed?

🔹 Step 2: Evaluating & Researching (Top-Down)

• How can we align the diverse needs of different residents?

• What scenarios are possible, and which ones best support the revitalization of the neighbourhood?

• What are the technical properties of the materials (following testing), and what are their best applications?

🔹 Step 3: Participating (Bottom-Up)

• Engaging residents in the decision-making process.

• Selecting the preferred scenario through collaboration.

🔹 Step 4: Implementing (Top-Down)

• Translating the chosen scenario into a technical design and execution plan.

🔹 Step 5: Co-Creation (Bottom-Up)

• Actively involving local and protected workplaces and residents in the construction process.

Simultaneously, the process combines both top-down and bottom-up approaches. On one hand, the design must be strongly rooted in its urban and social context. On the other, the development of the buildings starts from the perspective of the people who will use them—residents, temporary occupants, and passersby.

We apply the principle of balancing macro and micro perspectives, always keeping both the broader vision and the smallest detail in focus. An iterative approach allows these perspectives to intersect, with feedback refining the process at key moments.

A deep knowledge of the existing conditions is essential to define the impact of interventions. Developing a master plan at multiple levels (neighbourhood-building-material) serves as a roadmap—both during and after construction.

🔹 Step 1: Listening & Understanding (Bottom-Up)

• Understanding the stories behind people—what are their needs, backgrounds, and daily challenges?

• Understanding the stories behind materials—where do they come from, and how can they be repurposed?

🔹 Step 2: Evaluating & Researching (Top-Down)

• How can we align the diverse needs of different residents?

• What scenarios are possible, and which ones best support the revitalization of the neighbourhood?

• What are the technical properties of the materials (following testing), and what are their best applications?

🔹 Step 3: Participating (Bottom-Up)

• Engaging residents in the decision-making process.

• Selecting the preferred scenario through collaboration.

🔹 Step 4: Implementing (Top-Down)

• Translating the chosen scenario into a technical design and execution plan.

🔹 Step 5: Co-Creation (Bottom-Up)

• Actively involving local and protected workplaces and residents in the construction process.

Replacement construction and renovations are crucial in today's complex urban European environments, where space is limited and densification is necessary. They enable the creation of modern, energy-efficient buildings while preserving existing infrastructure and minimizing environmental impact. To optimize land use without contributing to urban sprawl, we must prioritize replacement construction and renovation.

The process we followed for material reuse provides valuable knowledge for other projects looking to incorporate reclaimed materials—an approach that will need to be increasingly implemented in the transition to a circular economy. This process includes dismantling, storage, testing and quality control, and reassembly, along with key information such as the quantity of recovered materials, costs, types of testing, methods for disassembly, storage, and reintegration, as well as related insurance requirements and specifications.

The project was part of a study conducted by Buildwise, which monitored various demolition projects that incorporated material recovery.

The process we followed for material reuse provides valuable knowledge for other projects looking to incorporate reclaimed materials—an approach that will need to be increasingly implemented in the transition to a circular economy. This process includes dismantling, storage, testing and quality control, and reassembly, along with key information such as the quantity of recovered materials, costs, types of testing, methods for disassembly, storage, and reintegration, as well as related insurance requirements and specifications.

The project was part of a study conducted by Buildwise, which monitored various demolition projects that incorporated material recovery.

Demographic shifts, migration patterns, and the exclusion of vulnerable populations are pressing urban challenges. This project addresses these issues through strategic urban integration and a carefully calibrated mix of housing typologies that promote inclusivity and resilience. The dual-unit concept allows for adaptable living configurations, responding to evolving household structures and demographic flux. Shared spatial infrastructures—such as common spaces, the public inner area, and adaptable layouts—foster social interaction and mitigate isolation. By embedding flexibility at both the architectural and urban scale, the project supports socio-economic diversity and long-term community stability.

The construction sector is a major contributor to global carbon emissions, largely due to energy-intensive material production and waste. A critical strategy for reducing this impact is preserving embodied energy—the total energy embedded in materials through extraction, processing, and transport. Rather than downcycling or discarding high-value components, this project prioritizes direct material reuse, reducing demand for virgin resources. By integrating reclaimed materials, the project minimizes waste streams and carbon footprints while demonstrating the feasibility of circular construction at scale.

The construction sector is a major contributor to global carbon emissions, largely due to energy-intensive material production and waste. A critical strategy for reducing this impact is preserving embodied energy—the total energy embedded in materials through extraction, processing, and transport. Rather than downcycling or discarding high-value components, this project prioritizes direct material reuse, reducing demand for virgin resources. By integrating reclaimed materials, the project minimizes waste streams and carbon footprints while demonstrating the feasibility of circular construction at scale.

The project was completed only a few months ago, and the landscaping—part of a separate project—will be carried out next year. As both elements are still recent or ongoing, it is too early to fully assess the project's outcomes and impact.

However, the following conclusions can already be drawn:

• The project has given the neighbourhood a renewed impetus. Other homeowners have been motivated to renovate their houses, often with the same contractor who carried out the project’s construction.

• The participation and co-creation processes have strengthened the bond between residents.

• Residents of the dual-units have started personalizing the shared winter garden together (adding frames, floor mats, shelves, etc.).

• Some families prefer limited social interaction with neighbours, which is respected.

• The reused materials have become a conversation starter in the neighbourhood, with residents becoming strong ambassadors for the circular economy. 😉

We look forward to summer and the redevelopment of the inner area, which will further encourage spontaneous interactions.

However, the following conclusions can already be drawn:

• The project has given the neighbourhood a renewed impetus. Other homeowners have been motivated to renovate their houses, often with the same contractor who carried out the project’s construction.

• The participation and co-creation processes have strengthened the bond between residents.

• Residents of the dual-units have started personalizing the shared winter garden together (adding frames, floor mats, shelves, etc.).

• Some families prefer limited social interaction with neighbours, which is respected.

• The reused materials have become a conversation starter in the neighbourhood, with residents becoming strong ambassadors for the circular economy. 😉

We look forward to summer and the redevelopment of the inner area, which will further encourage spontaneous interactions.