Reconnecting with nature

Climate Change as a Game

Climate Change as a Game. (Co)Designing with Children the Landscape of the Future

Today’s new generations, particularly young people, will face consistent landscape changes in their lives. Can we involve children and university students in co-designing landscapes that consider climate change?

Starting from exploring different forms of "play," the project aims to educate and engage younger generations in climate change issues. Games serve as tools for students to acquire knowledge, view the world from diverse perspectives, and ultimately imagine and transform the future.

Starting from exploring different forms of "play," the project aims to educate and engage younger generations in climate change issues. Games serve as tools for students to acquire knowledge, view the world from diverse perspectives, and ultimately imagine and transform the future.

Netherlands

Local

Delft Hout / Pijnacker

It addresses urban-rural linkages

It refers to other types of transformations (soft investment)

Yes

2024-06-30

No

No

No

As an individual

Today’s new generations, and in particular young people, will face consistent landscape changes during their existence. Can we create consciousness in young generations of how climate change will modify landscapes? Can we involve children and university students in co-designing the landscape considering climate change? Can we develop new educational methods and co-designed techniques for primary and tertiary education? How can we foster a positive attitude towards tackling the climate transition that inspires action in contact with nature?

This project is the product of the experimental Comenius course focused on pedagogical innovation. The course aims to educate and engage younger generations on climate change issues by exploring various types of outdoor games (role play, art installations, etc.) through exploration, co-design, and co-creation practices in a rural biodynamic area of the peri-urban landscapes of Delft, The Netherlands. Agricultural landscapes, especially those at the urban edge, can serve as teaching and learning laboratories for some of the challenges presented by climate change. Students from landscape architecture, architecture, and urban disciplines become ‘agents of change’ by involving children, teachers, parents, farmers, and visible and invisible living organisms in the co-design and co-creation processes to envision possible futures for the climate transition, finally creating a collective game-installation for children on-site. The game enables students to gain knowledge, view the world from different perspectives, and ultimately envision the future of landscapes alongside the challenges of biodiversity, soil, and water. Adopting different roles during play evokes emotions that foster new awareness, develop a more nuanced vision of the future, and inform decision-making. This encourages a more positive attitude toward addressing climate change through playful and emotional participatory methods that bring life to a ‘Playful Pedagogy.’

This project is the product of the experimental Comenius course focused on pedagogical innovation. The course aims to educate and engage younger generations on climate change issues by exploring various types of outdoor games (role play, art installations, etc.) through exploration, co-design, and co-creation practices in a rural biodynamic area of the peri-urban landscapes of Delft, The Netherlands. Agricultural landscapes, especially those at the urban edge, can serve as teaching and learning laboratories for some of the challenges presented by climate change. Students from landscape architecture, architecture, and urban disciplines become ‘agents of change’ by involving children, teachers, parents, farmers, and visible and invisible living organisms in the co-design and co-creation processes to envision possible futures for the climate transition, finally creating a collective game-installation for children on-site. The game enables students to gain knowledge, view the world from different perspectives, and ultimately envision the future of landscapes alongside the challenges of biodiversity, soil, and water. Adopting different roles during play evokes emotions that foster new awareness, develop a more nuanced vision of the future, and inform decision-making. This encourages a more positive attitude toward addressing climate change through playful and emotional participatory methods that bring life to a ‘Playful Pedagogy.’

Climate change, water and soil, biodiversity

Young generations (children, university students)

Human and more-than-human

Playful pedagogies

Landscape education

Our project embodies sustainability by integrating ecological awareness, participatory design, and innovative educational methods to address climate change. The initiative fosters regenerative landscape practices, biodiversity enhancement, and climate resilience while engaging diverse stakeholders in co-creative processes.

Key objectives met:

1. Regenerative Landscapes & Carbon Storage:

o The project promotes sustainable land management at a rural site, prioritizing peatland restoration, biodiversity conservation, and carbon sequestration.

o Strategies such as paludiculture, agroforestry, and crop rotation enhance soil health and water retention, reducing greenhouse gas emissions and supporting local ecosystems.

2. Education through Play & Artistic Engagement:

o Through role-playing, climate games, and outdoor installations, children and students engage in experiential learning, fostering emotional connections with environmental issues.

o The Whispering Wilderness installation serves as an interactive space where young participants learn about biodiversity, soil health, and climate change impacts through art and movement.

3. Co-Design, co-creation, and Participatory Approaches:

o A collaborative process with university students, children, educators, farmers, ensures that local knowledge and sustainable agricultural practices shape the future of the landscape.

o This participatory approach ensures that solutions are deeply rooted in both scientific research and community needs.

4. Multifunctionality & Ecosystem Resilience:

o The project balances ecological, economic, and recreational functions of the landscape, ensuring that nature-based solutions contribute to long-term resilience.

This initiative stands out as a model for integrating landscape regeneration, climate education, and participatory design in a holistic manner, merging scientific knowledge with creative pedagogiesEducation and action can inspire a new generation for a sustainable future.

Key objectives met:

1. Regenerative Landscapes & Carbon Storage:

o The project promotes sustainable land management at a rural site, prioritizing peatland restoration, biodiversity conservation, and carbon sequestration.

o Strategies such as paludiculture, agroforestry, and crop rotation enhance soil health and water retention, reducing greenhouse gas emissions and supporting local ecosystems.

2. Education through Play & Artistic Engagement:

o Through role-playing, climate games, and outdoor installations, children and students engage in experiential learning, fostering emotional connections with environmental issues.

o The Whispering Wilderness installation serves as an interactive space where young participants learn about biodiversity, soil health, and climate change impacts through art and movement.

3. Co-Design, co-creation, and Participatory Approaches:

o A collaborative process with university students, children, educators, farmers, ensures that local knowledge and sustainable agricultural practices shape the future of the landscape.

o This participatory approach ensures that solutions are deeply rooted in both scientific research and community needs.

4. Multifunctionality & Ecosystem Resilience:

o The project balances ecological, economic, and recreational functions of the landscape, ensuring that nature-based solutions contribute to long-term resilience.

This initiative stands out as a model for integrating landscape regeneration, climate education, and participatory design in a holistic manner, merging scientific knowledge with creative pedagogiesEducation and action can inspire a new generation for a sustainable future.

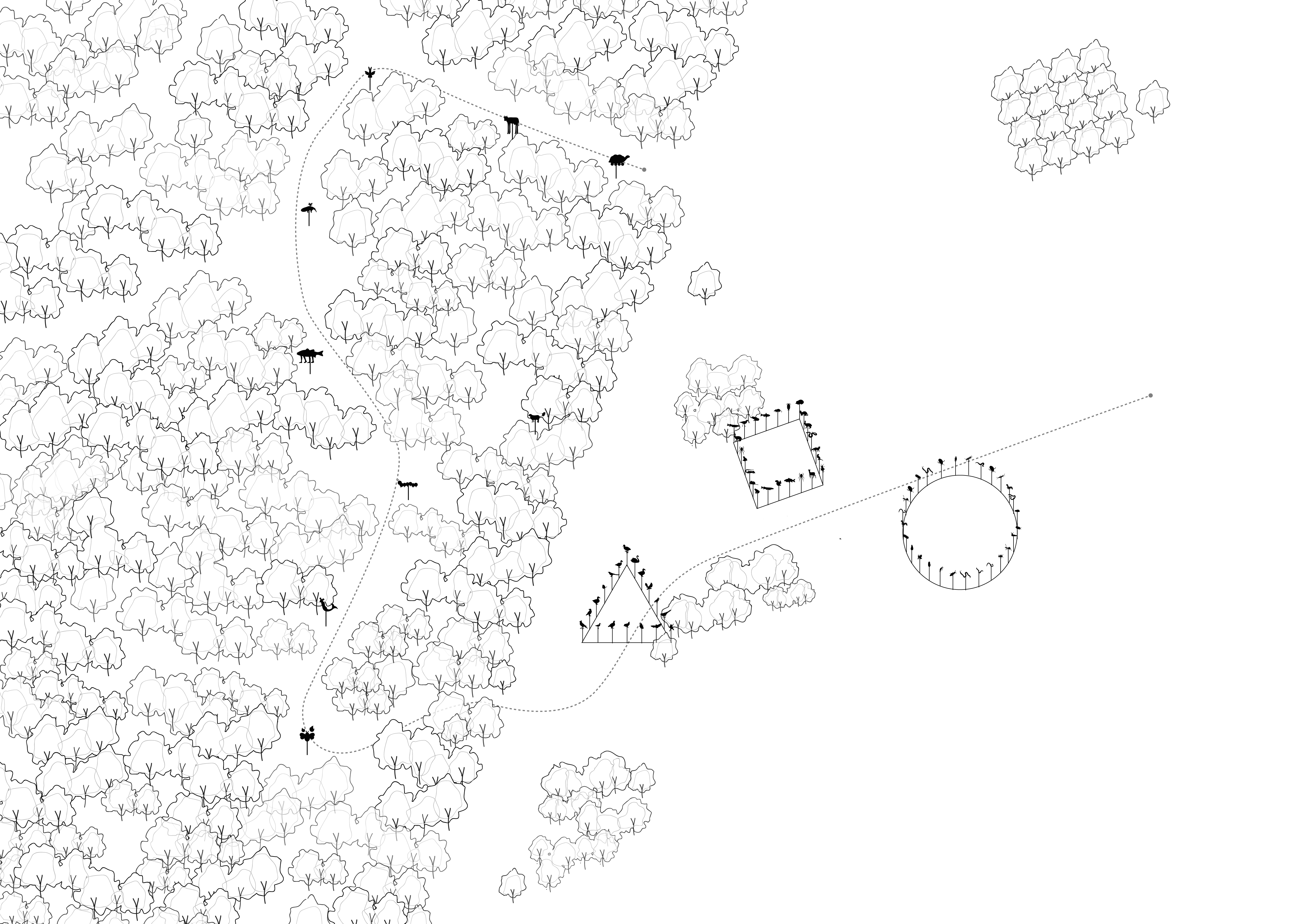

The Whispering Wilderness installation offers a unique sensory, artistic, and immersive experience that fosters a deeper connection between people, nature, and climate awareness. Wild play choreographies and installations in the Polder guide you through ‘The Dream’ in the Forest. The educational event encouraged children to explore various animal species through installations divided into three habitat groups—air, land, and underground animals—displayed in triangle, square, and circle elementary forms. Constructed from wood and designed with principles of simplicity, temporariness, and imagination, the installation transforms the landscape into an interactive and poetic space, encouraging play, storytelling, and reflection on environmental change:

1. Aesthetic Simplicity & Integration with Nature

- The installation’s minimalistic wooden structure and organic forms allow it to blend with its natural surroundings.

2. Imaginative and Playful Design

- The design distills complex climate and biodiversity themes into visual narratives by using basic geometric shapes (triangles, squares, circles) to represent animal species. This simplicity sparks curiosity and invites participants to engage in imaginative play.

- Through games, role-playing, and movement, participants connect emotionally with environmental themes, making learning an embodied experience rather than passive observation.

3. Cultural & Educational Benefits

- The project brings together students, children, and farmers, merging scientific knowledge with artistic expression, reinforcing culture as a vehicle for sustainability.

- Inspired by Henri Rousseau’s 'The Dream,' the installation in the forest fosters an artistic reimagining of animal evolutions (e.g. the fish with legs for dry periods).

4. Ephemeral Beauty

- Designed as a temporary installation, it reflects the fleeting nature of landscapes under climate change.

- Its reversible and biodegradable materials to ensure low ecological footprint.

1. Aesthetic Simplicity & Integration with Nature

- The installation’s minimalistic wooden structure and organic forms allow it to blend with its natural surroundings.

2. Imaginative and Playful Design

- The design distills complex climate and biodiversity themes into visual narratives by using basic geometric shapes (triangles, squares, circles) to represent animal species. This simplicity sparks curiosity and invites participants to engage in imaginative play.

- Through games, role-playing, and movement, participants connect emotionally with environmental themes, making learning an embodied experience rather than passive observation.

3. Cultural & Educational Benefits

- The project brings together students, children, and farmers, merging scientific knowledge with artistic expression, reinforcing culture as a vehicle for sustainability.

- Inspired by Henri Rousseau’s 'The Dream,' the installation in the forest fosters an artistic reimagining of animal evolutions (e.g. the fish with legs for dry periods).

4. Ephemeral Beauty

- Designed as a temporary installation, it reflects the fleeting nature of landscapes under climate change.

- Its reversible and biodegradable materials to ensure low ecological footprint.

The project exemplifies the inclusion principle by integrating accessibility, affordability, and participatory governance in its approach to climate-conscious landscape design. By engaging children, university students, farmers, teachers, and even non-human organisms, the initiative fosters inclusive and collaborative learning experiences that transcend traditional educational models.

Accessibility & Affordability

The project ensures open and inclusive participation by conducting activities in public rural landscapes and a biodynamic farm, making sustainability education accessible to diverse communities. The use of low-cost, natural materials for installations reinforces affordability while emphasizing environmental responsibility.

Design for All & New Societal Models

By incorporating co-design and co-creation methods, students from landscape architecture, urbanism, and architecture become agents of change, facilitating dialogue across generations. The outdoor game-installation, shaped through participatory workshops, allows children to engage with climate challenges through play, fostering emotional connections with biodiversity, soil, and water.

Inclusive Governance & Participatory Processes

Collaboration with local farmers, educators, and children exemplifies a bottom-up governance approach, ensuring that community voices shape future landscapes. The project’s pedagogical innovation introduces a "Playful Pedagogy", where role-playing games, installations, and storytelling encourage new ways of thinking about climate action.

Exemplary Impact

The project redefines education by making climate awareness engaging, emotional, and experiential. It demonstrates how art, play, and co-creation can inspire long-term stewardship of landscapes, creating a replicable model for sustainable, inclusive, and future-oriented environmental education.

Accessibility & Affordability

The project ensures open and inclusive participation by conducting activities in public rural landscapes and a biodynamic farm, making sustainability education accessible to diverse communities. The use of low-cost, natural materials for installations reinforces affordability while emphasizing environmental responsibility.

Design for All & New Societal Models

By incorporating co-design and co-creation methods, students from landscape architecture, urbanism, and architecture become agents of change, facilitating dialogue across generations. The outdoor game-installation, shaped through participatory workshops, allows children to engage with climate challenges through play, fostering emotional connections with biodiversity, soil, and water.

Inclusive Governance & Participatory Processes

Collaboration with local farmers, educators, and children exemplifies a bottom-up governance approach, ensuring that community voices shape future landscapes. The project’s pedagogical innovation introduces a "Playful Pedagogy", where role-playing games, installations, and storytelling encourage new ways of thinking about climate action.

Exemplary Impact

The project redefines education by making climate awareness engaging, emotional, and experiential. It demonstrates how art, play, and co-creation can inspire long-term stewardship of landscapes, creating a replicable model for sustainable, inclusive, and future-oriented environmental education.

The project had a profound impact on civil society by empowering various groups to engage actively in landscape and climate matters.

Students: They emerged as key agents of change, enhancing their creativity and developing skills in participatory methods and teaching. By engaging in emotional participatory processes, they fostered a more positive outlook on climate change, while also sharing their knowledge with children.

Children: Actively participating in co-design activities, children learned about vital topics like biodiversity and the water and soil cycles, also taking on roles as 'teachers'. Their involvement in fun and emotional processes helped them adopt a proactive attitude towards climate change issues.

Teachers: University instructors and primary education teachers played a crucial role in guiding students, enhancing their participatory planning and teaching skills. They fostered innovation in teaching landscape education related to climate change and successfully implemented landscape pedagogy in both tertiary and primary levels.

The project sparked innovation by focusing on landscape design and climate change through playful learning methods and emotional strategies.

Farmer/Owner: She gained insights into future landscape scenarios and participated in co-designing a master plan for her area, which is set to become a permanent installation attracting visitors of all ages.

More-than-Human: The project benefitted from a master plan that emphasizes protecting landscapes and promoting biodiversity in rural areas.

Parents: Through their children’s learning, parents acquired insights into landscape-related climate change, effectively making their children into their teachers.

Students: They emerged as key agents of change, enhancing their creativity and developing skills in participatory methods and teaching. By engaging in emotional participatory processes, they fostered a more positive outlook on climate change, while also sharing their knowledge with children.

Children: Actively participating in co-design activities, children learned about vital topics like biodiversity and the water and soil cycles, also taking on roles as 'teachers'. Their involvement in fun and emotional processes helped them adopt a proactive attitude towards climate change issues.

Teachers: University instructors and primary education teachers played a crucial role in guiding students, enhancing their participatory planning and teaching skills. They fostered innovation in teaching landscape education related to climate change and successfully implemented landscape pedagogy in both tertiary and primary levels.

The project sparked innovation by focusing on landscape design and climate change through playful learning methods and emotional strategies.

Farmer/Owner: She gained insights into future landscape scenarios and participated in co-designing a master plan for her area, which is set to become a permanent installation attracting visitors of all ages.

More-than-Human: The project benefitted from a master plan that emphasizes protecting landscapes and promoting biodiversity in rural areas.

Parents: Through their children’s learning, parents acquired insights into landscape-related climate change, effectively making their children into their teachers.

The project engaged stakeholders at multiple levels in the design and implementation of the project.

At the academic level, TU Delft contributed through three university teachers: a landscape guiding professor, a construction professor, and a pedagogy specialist, ensuring feasibility and coherence in the game development.

Nine TU Delft students from landscape architecture, architecture, and urbanism programs led different phases based on their expertise. Three landscape architecture students directed the first phase, "Exploring and Playing the Landscape," focusing on landscape understanding and sustainability. Three urban design students led the second phase, "(Co)Designing the Landscape," emphasizing urban-landscape planning according to sustainable principles, while the last three architecture students managed the third phase, "(Co)Creating the Landscape," addressing architectural composition and bringing aesthetic quality to the installation. The involvement of both international and Dutch-speaking students fostered inclusive communication with children.

At the local level, 28 children (aged 11) and two primary school teachers from Groen van Prinstererschool in Voorburg were key contributors. Their insights shaped the co-design and co-creation processes from a child’s perspective. One of the primary school teachers played a crucial role in integrating pedagogical knowledge.

A local farmer, who owns the investigation/installation site (Stiltegoed in Delft Hout), was actively involved in the (co)design and (co)creation phases, bridging practical and ecological considerations.

Parents were invited to participate in the (co)creating phase, fostering community involvement.

Additionally, the project incorporated a perspective that was more than human, considering animals, soil, bacteria, and plants, reinforcing sustainability and ecological balance.

At the academic level, TU Delft contributed through three university teachers: a landscape guiding professor, a construction professor, and a pedagogy specialist, ensuring feasibility and coherence in the game development.

Nine TU Delft students from landscape architecture, architecture, and urbanism programs led different phases based on their expertise. Three landscape architecture students directed the first phase, "Exploring and Playing the Landscape," focusing on landscape understanding and sustainability. Three urban design students led the second phase, "(Co)Designing the Landscape," emphasizing urban-landscape planning according to sustainable principles, while the last three architecture students managed the third phase, "(Co)Creating the Landscape," addressing architectural composition and bringing aesthetic quality to the installation. The involvement of both international and Dutch-speaking students fostered inclusive communication with children.

At the local level, 28 children (aged 11) and two primary school teachers from Groen van Prinstererschool in Voorburg were key contributors. Their insights shaped the co-design and co-creation processes from a child’s perspective. One of the primary school teachers played a crucial role in integrating pedagogical knowledge.

A local farmer, who owns the investigation/installation site (Stiltegoed in Delft Hout), was actively involved in the (co)design and (co)creation phases, bridging practical and ecological considerations.

Parents were invited to participate in the (co)creating phase, fostering community involvement.

Additionally, the project incorporated a perspective that was more than human, considering animals, soil, bacteria, and plants, reinforcing sustainability and ecological balance.

The project's design and implementation involved multiple disciplines, including landscape architecture, urban design, architecture, building technology, and expertise in children's education. The course welcomed students from different disciplines, fostering cross-disciplinary learning throughout its various phases. Each course phase values a different discipline and student's expertise. The first course phase focused on landscape issues, the second on planning, and the third on architectural composition. As a result, students became the instructors for their peers in their specialized fields. Each phase was led by a different group of students to align with varied learning objectives and to provide opportunities for mutual learning:

Phase 1: Led by landscape architecture students, this phase, titled ‘Exploring and Playing the Landscape’, focused on climate issues like water and biodiversity. Students conducted fieldwork and later organized a playful workshop for children, teaching them about the site through engaging assignments.

Phase 2: Urban design students directed ‘(Co)Designing the Landscape’, where they created a climate plan for the area. Engaging with the site's farmer/owner brought practical insight into co-designing solutions. The students held another workshop in which children constructed dioramas representing their envisioned future landscapes.

Phase 3: Architecture students led ‘(Co)Creating the Landscape’, emphasizing architectural design and transferring the acquired scientific knowledge to aesthetic qualities. Drawing inspiration from the children's previous workshop, students developed installation designs, also evaluated by a building technology and pedagogical experts on feasibility and sustainability. They selected an installation project to prototype and build, engaging with the children to transform conceptual ideas into tangible creations while also involving parents and teachers in the process.

Phase 1: Led by landscape architecture students, this phase, titled ‘Exploring and Playing the Landscape’, focused on climate issues like water and biodiversity. Students conducted fieldwork and later organized a playful workshop for children, teaching them about the site through engaging assignments.

Phase 2: Urban design students directed ‘(Co)Designing the Landscape’, where they created a climate plan for the area. Engaging with the site's farmer/owner brought practical insight into co-designing solutions. The students held another workshop in which children constructed dioramas representing their envisioned future landscapes.

Phase 3: Architecture students led ‘(Co)Creating the Landscape’, emphasizing architectural design and transferring the acquired scientific knowledge to aesthetic qualities. Drawing inspiration from the children's previous workshop, students developed installation designs, also evaluated by a building technology and pedagogical experts on feasibility and sustainability. They selected an installation project to prototype and build, engaging with the children to transform conceptual ideas into tangible creations while also involving parents and teachers in the process.

The project is indeed a project, but above all, a ‘project of mutually interlaced processes.’ The project’s uniqueness extends to its engagement with diverse stakeholders, including students, teachers, parents, animals, and farmers, through playful-artful and playful-serious games. This interconnected network fosters a holistic learning environment where different perspectives converge to enrich the design and execution phases. The primary innovative process is that TU Delft students become the children's teachers, gaining empowerment and learning to transmit knowledge. In a virtuous cycle, children, in turn, educate their parents. The presence of teachers ensures sustainable landscape knowledge. Farmers and animals introduce an ecological dimension, reinforcing sustainability and nature-based learning. Being outdoors, in the landscape, rather than in class can lead to better inductive knowledge. The collaborative process instills a sense of ownership among stakeholders, ensuring the play installation is not merely an external imposition but an integrated, meaningful space for the community combining play and art with science.

The play installation also represents a groundbreaking departure from conventional playground projects. Unlike standardized designs, by integrating the perspectives of children and university students, the installation becomes a living, evolving entity rather than a static, predetermined structure. This project's conceptual framework and methodologies set a precedent for future participatory design efforts, fostering a legacy of innovation in educational and urban-landscape playful and learning spaces. By prioritizing process over permanence, this project challenges conventional approaches to playground design and highlights the enduring value of co-creative learning experiences. Although the installation itself is temporary, the knowledge, skills, and relationships forged through the process endure beyond its physical presence.

The play installation also represents a groundbreaking departure from conventional playground projects. Unlike standardized designs, by integrating the perspectives of children and university students, the installation becomes a living, evolving entity rather than a static, predetermined structure. This project's conceptual framework and methodologies set a precedent for future participatory design efforts, fostering a legacy of innovation in educational and urban-landscape playful and learning spaces. By prioritizing process over permanence, this project challenges conventional approaches to playground design and highlights the enduring value of co-creative learning experiences. Although the installation itself is temporary, the knowledge, skills, and relationships forged through the process endure beyond its physical presence.

Methodology plays a crucial role in the process. The course set three phases, including three workshops to explore, (co)design, and (co)create the landscape. Each phase adopts different methods.

In the first phase, Exploring and Playing the Landscape, students investigate the designated site, concentrating on climate issues such as water, soil, biodiversity. Their methods include fieldwork, mapping processes, and research through design. Utilizing this knowledge, the students organize the first playful workshop for children on-site to jointly explore the landscape in a playful and informative workshop.

Learnings: landscape analysis, climate change issues

Methods: Playful methods, fieldwork, research through design

In the second phase, (Co)Designing the Landscape, students collaborate with the farmer to (co)design alternative scenarios and a master plan for the site. In a second indoor workshop with children, students try to understand their perspectives on climate issues and brainstorm potential games together using a paper model of the site area. Inspired by this workshop, students create games tailored to the site's specific context. The most promising game installation is collectively selected for construction.

Learnings: urban and landscape planning, climate change issues

Methods: alternative scenarios, co-design processes, playful methods

In the third phase, (Co)Creating the Landscape, students (co)construct the selected game-installation in the study area. They invite the children to (co)play and (co)test the landscape game about carbon cycle and biodiversity. Teachers and parents are also invited to participate. A questionnaire about learning is handed in to children before the start of the game and after experiencing the game to understand what they learnt.

Learnings: architecture composition, landscape architecture, modelling and prototyping, construction

Methods: Playful methods, interviews, co-creation methods

In the first phase, Exploring and Playing the Landscape, students investigate the designated site, concentrating on climate issues such as water, soil, biodiversity. Their methods include fieldwork, mapping processes, and research through design. Utilizing this knowledge, the students organize the first playful workshop for children on-site to jointly explore the landscape in a playful and informative workshop.

Learnings: landscape analysis, climate change issues

Methods: Playful methods, fieldwork, research through design

In the second phase, (Co)Designing the Landscape, students collaborate with the farmer to (co)design alternative scenarios and a master plan for the site. In a second indoor workshop with children, students try to understand their perspectives on climate issues and brainstorm potential games together using a paper model of the site area. Inspired by this workshop, students create games tailored to the site's specific context. The most promising game installation is collectively selected for construction.

Learnings: urban and landscape planning, climate change issues

Methods: alternative scenarios, co-design processes, playful methods

In the third phase, (Co)Creating the Landscape, students (co)construct the selected game-installation in the study area. They invite the children to (co)play and (co)test the landscape game about carbon cycle and biodiversity. Teachers and parents are also invited to participate. A questionnaire about learning is handed in to children before the start of the game and after experiencing the game to understand what they learnt.

Learnings: architecture composition, landscape architecture, modelling and prototyping, construction

Methods: Playful methods, interviews, co-creation methods

Many elements of the project can be replicated, transformed and adapted.

Methodology and Processes

Playful learning methodologies, co-design methods focused on landscape and climate change, and the integration of emotional approaches into landscape design can be easily transferred.

I am replicating the experience at the same site this year, with new students from my university and a different class of children of the same age. The course can be replicated based on the format and methodology I adopted.

Products

The playful installation can be replicated and transferred. We are currently creating a more permanent version of the game installation using different materials (corten instead of wood). To gain insights into the game's final learnings, we will co-test it with another group of students who did not participate in the project.

Given its elementary forms (square, circle, triangle), the installation can be moved to another context. The knowledge becomes less site-specific, but the game and play remain valid. Additionally, the fantasy animals envisioned by the children can create an inspiring installation when relocated. Moreover, all games implemented throughout the course can be replicated: for instance, the red dot game addressing the climate crisis and the green dot game representing climate hope, as well as the lively choreographies mimicking animal behavior and ecological needs that occurred at the end of the installation day.

Learnings and Knowledge

The installation and the course itself can also benefit other audiences and can be proposed to adults. The game is not just for children; it promotes understanding of climate change, biodiversity, and climate-carbon futures.

Methodology and Processes

Playful learning methodologies, co-design methods focused on landscape and climate change, and the integration of emotional approaches into landscape design can be easily transferred.

I am replicating the experience at the same site this year, with new students from my university and a different class of children of the same age. The course can be replicated based on the format and methodology I adopted.

Products

The playful installation can be replicated and transferred. We are currently creating a more permanent version of the game installation using different materials (corten instead of wood). To gain insights into the game's final learnings, we will co-test it with another group of students who did not participate in the project.

Given its elementary forms (square, circle, triangle), the installation can be moved to another context. The knowledge becomes less site-specific, but the game and play remain valid. Additionally, the fantasy animals envisioned by the children can create an inspiring installation when relocated. Moreover, all games implemented throughout the course can be replicated: for instance, the red dot game addressing the climate crisis and the green dot game representing climate hope, as well as the lively choreographies mimicking animal behavior and ecological needs that occurred at the end of the installation day.

Learnings and Knowledge

The installation and the course itself can also benefit other audiences and can be proposed to adults. The game is not just for children; it promotes understanding of climate change, biodiversity, and climate-carbon futures.

This project addresses global climate challenges by providing local, participatory solutions that engage younger generations in climate-conscious landscape co-design. It has demonstrated how local contingencies can be scaled up globally. Through site investigation, hands-on learning, and interactive installations, it fosters awareness of biodiversity, soil health, water cycles, and climate resilience.

The site investigation highlights key environmental challenges, including carbon storage loss due to peatland degradation, soil fertility decline, and flood risks from poor drainage. By studying Delftse Hout’s landscape and the biodynamic farm Stiltegoed, students explore sustainable practices such as water management, crop rotation, and biodiversity conservation. These localized solutions mitigate climate change impacts by restoring peatlands, enhancing soil health, and promoting regenerative agriculture.

The ‘co-design the landscape’ phase generated alternative scenarios alongside the farmer, aiding in addressing the impacts of climate change on this agricultural area, as well as its flora and fauna, and identifying potential interventions for both the short and long term.

Finally, the co-created installation, Whispering Wilderness, turns learning into an immersive and playful experience. Children connect emotionally with climate change, biodiversity loss, and ecosystem functions through interactive animal habitats and role-playing games. The installation encourages young learners to envision future landscapes and take on the role of stewards of the environment beyond the local site.

By integrating art, science, and education, this project empowers children and students as agents of change and showcases how local soil, water, and biodiversity management interventions can aid global sustainability efforts.

The site investigation highlights key environmental challenges, including carbon storage loss due to peatland degradation, soil fertility decline, and flood risks from poor drainage. By studying Delftse Hout’s landscape and the biodynamic farm Stiltegoed, students explore sustainable practices such as water management, crop rotation, and biodiversity conservation. These localized solutions mitigate climate change impacts by restoring peatlands, enhancing soil health, and promoting regenerative agriculture.

The ‘co-design the landscape’ phase generated alternative scenarios alongside the farmer, aiding in addressing the impacts of climate change on this agricultural area, as well as its flora and fauna, and identifying potential interventions for both the short and long term.

Finally, the co-created installation, Whispering Wilderness, turns learning into an immersive and playful experience. Children connect emotionally with climate change, biodiversity loss, and ecosystem functions through interactive animal habitats and role-playing games. The installation encourages young learners to envision future landscapes and take on the role of stewards of the environment beyond the local site.

By integrating art, science, and education, this project empowers children and students as agents of change and showcases how local soil, water, and biodiversity management interventions can aid global sustainability efforts.

The course featured numerous innovations, demonstrating short-term and long-term impacts by reconnecting with nature to address climate transition.

First, most crucial phases of the course take place outdoors, in the landscape, helping us understand that we can learn from nature and its living beings. The landscape is the outdoor class.

Second, the climate transition was introduced as a game, allowing students to develop emotional connections with nature from both human and non-human perspectives. We incorporated role-playing games to personify natural elements and living systems, including being a cloud, being a river, being peat, being a worm, being a tree, or being a cow, to cultivate emotional engagement with natural systems.

Third, building the acquired knowledge of young generations on soil and water cycles and biodiversity, as well as learning about nature-based solutions for scenarios and master plans, lays the foundation for the next generation of agents of change. Students were amazed to know, for example, that more carbon is stored in soil than in the atmosphere and vegetation combined. One of the displayed installations, ‘Under Our Feet,’ allowed to imagine and learn about what lies beneath the ground and its potential for carbon storage. The (in)visible world beneath our feet is rich in biodiversity. Bacteria, fungi, protozoa, nematodes, arthropods, and earthworms are various life forms within the soil. This biodiversity is essential for maintaining soil health, enhancing plant growth, and contributing to ecosystem services such as nutrient cycling, carbon sequestration, and water filtration.

All participants, including primary school teachers and farmers, learned about these issues and became informal community educators.

To understand all these impacts on acquired knowledge, I conducted several questionnaires with children before and after they experienced the game and with university students before and after they completed the course.

First, most crucial phases of the course take place outdoors, in the landscape, helping us understand that we can learn from nature and its living beings. The landscape is the outdoor class.

Second, the climate transition was introduced as a game, allowing students to develop emotional connections with nature from both human and non-human perspectives. We incorporated role-playing games to personify natural elements and living systems, including being a cloud, being a river, being peat, being a worm, being a tree, or being a cow, to cultivate emotional engagement with natural systems.

Third, building the acquired knowledge of young generations on soil and water cycles and biodiversity, as well as learning about nature-based solutions for scenarios and master plans, lays the foundation for the next generation of agents of change. Students were amazed to know, for example, that more carbon is stored in soil than in the atmosphere and vegetation combined. One of the displayed installations, ‘Under Our Feet,’ allowed to imagine and learn about what lies beneath the ground and its potential for carbon storage. The (in)visible world beneath our feet is rich in biodiversity. Bacteria, fungi, protozoa, nematodes, arthropods, and earthworms are various life forms within the soil. This biodiversity is essential for maintaining soil health, enhancing plant growth, and contributing to ecosystem services such as nutrient cycling, carbon sequestration, and water filtration.

All participants, including primary school teachers and farmers, learned about these issues and became informal community educators.

To understand all these impacts on acquired knowledge, I conducted several questionnaires with children before and after they experienced the game and with university students before and after they completed the course.