Community Design for Living Architecture

Basic information

Project Title

Full project title

Category

Project Description

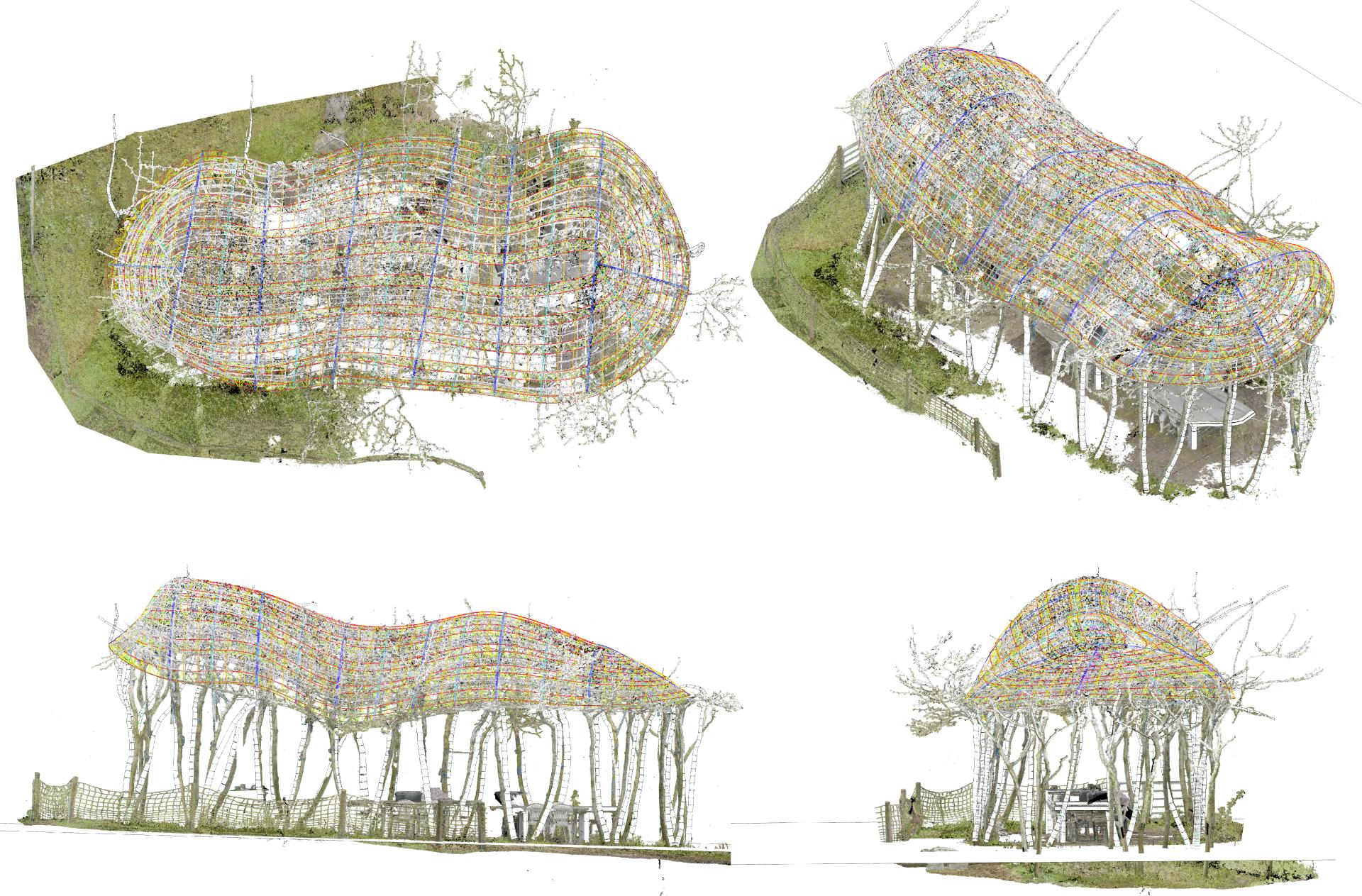

We apply digital tools for designers and communities to co-create with trees! Tools in scanning trees, simulating growth and mapping their structure allow for an open design process. Making these smooth and accessible puts decisions in the hands of communities and provides communication channels between designers, users, and experts. Our students applied such tools to design a growing Pavilion in Germany in 2021. We will expand this to wider communities in urban European contexts.

Geographical Scope

Project Region

Urban or rural issues

Physical or other transformations

EU Programme or fund

Which funds

Description of the project

Summary

Industrialised building processes using concrete, steel and timber products rely on homogenised material properties and static conditions to minimise complexity in design and construction. The resulting structures are standardized and simplistic, their functions are basic and predetermined with a defined period of use. In comparison, living tree structures are dynamic and heterogeneous. They have complex and diverse topologies and functions, and they provide benefits throughout growth, human use, and decay. Living architectures around the world such as German Tanzlinden are historic buildings that grow with their communities. They are resilient, carbon-positive tree structures of deep cultural wisdom, regenerating habitats and providing psychological benefits.

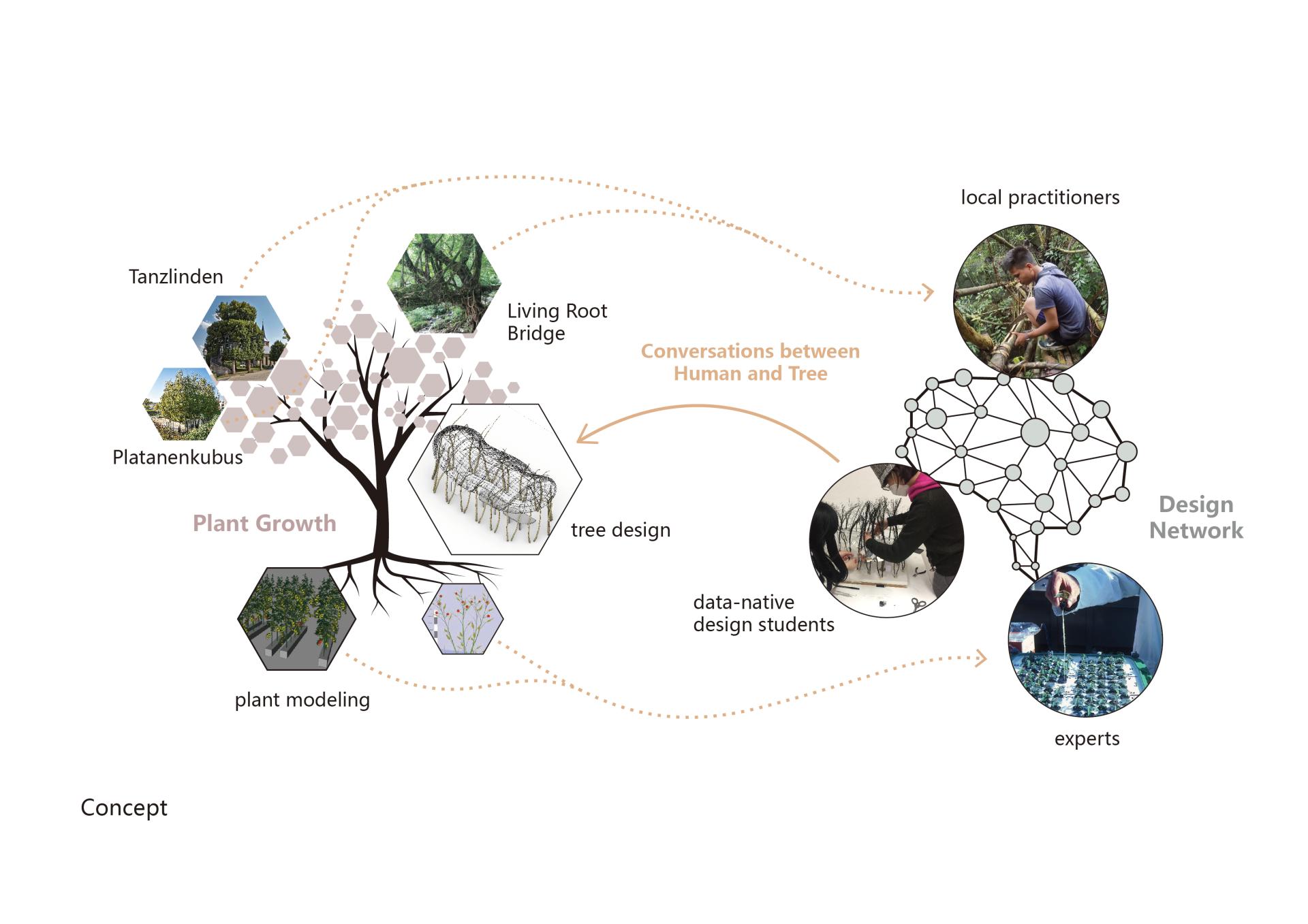

The recent revolutions in data acquisition, computing and sharing are pioneered by today’s data-native public. The effect of this is to give broader horizons to building design, which is not limited to standardised materials or to select few designers – details can be precisely mapped, and knowledge of environments can be communicated easily. This inspires a key question: how can architects utilise the data revolution to work with users in designing with living trees for new urban settings?

Future living Architecture designers should bring out the diverse potentials of trees. So we recall European living architecture traditions (such as the plane tree square in Labouheyre, France) through a data-first design approach. With this, architects can co-design and co-create with trees, in an iterative process where design decisions are not made once, but repeatedly throughout the tree's growth. We give designers, practitioners and users the tools to combine vernacular knowledge and the scientific state of the art. The paradigm in design thinking has shifted – understanding buildings as adaptive environmental, social and cultural systems, designed continuously with improving data and growth.

&#

Key objectives for sustainability

The current design paradigm places the operational time at the centre of the building life cycle, with raw materials processing, construction, deconstruction, and recycling playing secondary roles. While some materials are reusable, much of the building material is wasted – 54% of construction and demolition waste in the EU goes to landfill, making up 33% of unrecycled waste. This emphasis on operational time neglects the rest of the life cycle. In trees, the construction (growth), function (maturity) and end-of-life (regeneration or recycling) are essential to the life cycle. Accordingly, pruning, planting, and self-renewal are integral aspects of living architecture. While the life span of conventional buildings is defined by the decay of the material, living architecture can strengthen over time through the interplay of maintenance, growth and regeneration – many trees can live for hundreds of years. Furthermore, trees play a wider role in the built environment – they provide habitat corridors, reduce storm-water runoff, stabilise slopes, and clean polluted air.

Engaging with nature means understanding the temporal processes of living buildings and actively engaging with growth and decay as design principles. Tools in growth prediction and understanding trees’ physiological needs are well developed. So far, we have taught university students to do this with tools that allow for long-term planning and changes to designs that react to growth. However, this should not stop with designers – users must embrace these natural changes as well. We propose a step-change in public engagement with the built environment, giving users a new awareness of and engagement in the growth and change of their surroundings. Our tools, which so far have been applied in teaching, bring digital, data-driven design to stakeholders. Designs with users’ understanding of change at their heart embed regenerative design in a place, linking communities to their environments.

Key objectives for aesthetics and quality

The aesthetics of trees are deeply rooted in the origins of art. Aristotle tells us that ‘art takes nature as its model’. Trees’ diversity in species, shape, colour and texture inspired the romantics – as ideal forms and colours; and the impressionists – when light disperses through leaves, the environment is cast in fresh green. The dappled spots are images of the sun, dancing under the tree canopy.

For others, the balance of complexity and simplicity provides beauty. In The Algorithmic Beauty of Plants, Astrid Lindenmayer shows how countless species can be represented with small tweaks to simple algorithms. Growth processes also arise from complexity: trees draw on the air, water and ecological systems around them. Detailed data helps us understand these systems, and this data enmeshes beautifully, showing the tree’s embedment in its environment. With the development of virtual and augmented reality, emergent forms can now be visualised – users can see the role of their trees in the water cycle and project its growth into the future. This new understanding of the simplicity in emergent forms repositions Bauhaus – asking how simple natural processes combine function and beauty in a complex age?

Besides such visual pleasure, our approach integrates multiple senses: the smell, touch, and dynamics in seasons contribute to the overall experience of space. Based in the principles of biophilic design, for us the connections to nature are as important as the building itself. Our objective is to help architects, city planners and communities balance emergent biological complexity and stable system simplicity. This balance is central to our pavilion co-designed with the Sculpture Park Neue Kunst am Ried. The tree faithfully documents its growth, life story, changes of the environment and interaction with technical components. Each tree is a book, written and read the people who shape its growth. As these trees grow, they are woven into a story of place.

Key objectives for inclusion

Living architecture is pioneered by vernacular communities. The plane tree square in Labouheyre, France and the Tanzlinden in Germany bring together whole villages and multiple generations in growth, celebration, and care of buildings, just as hedge-laying traditions are shared between farmers across Europe. These social structures are the enabling conditions for living architecture, and stakeholder engagement is essential to the monitoring, maintenance, and growth of the buildings.

In our vision for designed living architecture, or ‘Baubotanik’, architects begin from the user-practitioner’s perspective. Just as, in traditional examples, the ongoing monitoring is performed by users as a communal exercise in which each person follows growth processes, imagines future growth and they decide together on the path ahead. With easy access to data, users can make decisions informed by their own local knowledge, by the plant’s growth history and by knowledge from experts in botany, ecology, and biomechanics. In one workflow, citizen-led photogrammetry will be analysed by biomechanics specialists and passed back to user-practitioner communities for maintenance decisions. Digital tools, using this shared data, are a platform for ongoing collaborative design and analysis.

In our recent Baubotanik Pavilion, students received training spanning growth prediction, topological modelling, and plant biomechanics, as well as conversations with the collaborating artist. We aim for all users of living architecture to have access to a broad understanding of the forces at play. With precise documented tree histories, groups can discuss the trees’ structure and physiology, the local environment and the aesthetic considerations of light and space. Local craftsman, residents and artists who visit the park also participated in the final installation of the Baubotanik Pavilion and were inspired in their own work by the combination of technological and natural growth.

Physical or other transformations

Innovative character

The central goal of this project is to increase awareness of trees in the city, both as living plants and as changing structures. By interacting daily with trees and having direct control over their growth, people learn the long-term changes, environmental interactions and annual patterns, sometimes through explicit learning, sometimes through meeting and playing with neighbours. This awareness enriches the story of place created by the project, and in doing so creates an aesthetic. To see this effect we only need look at the Tanzlinden: the history of community use is what gives these municipal trees their beauty.

By making care and attendance of trees a present part of people’s lives, we want to bring a deeper understanding of sustainability, including everyone in the progress towards sustainable, even regenerative, development. This can be enriched by data visualisations, predictive modelling, and understanding the complexity of ecosystems. Basing imagined built-and-grown environments in realistic projections, people are able to connect clearly with the sustainable future.

The long-term aesthetic developed here is essential to an inclusive understanding of sustainability. The alternative, sustainability that delegates processes and actions to places outside the lived environments, is unable to include city-dwellers. The simple act of following a tree through seasons and years, and the reciprocating benefits to our living spaces, are exactly the physical, aesthetic ties necessary for inclusive sustainability. In the coming decades, design in Europe will widely adopt living architecture and its core principles. In this light, future architects must learn to use data as a bridge between scientific disciplines and localised perspectives.